Fig.1

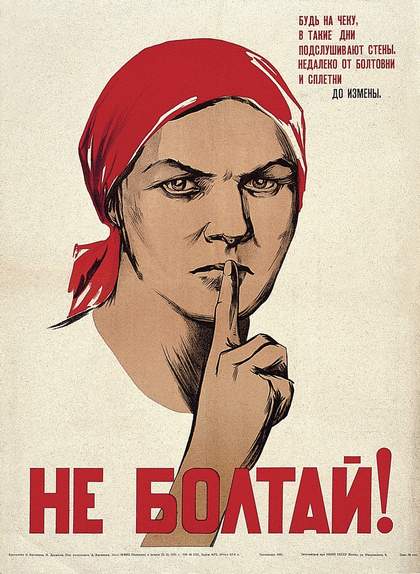

Konstantin Rotov, ‘Cave Age Bureaucracy’, in Krokodil, no.14, 1927, p.12

David King Collection, Tate Archive V DKC Serial Krokodil

At first sight the fortunes of two Soviet cartoonists, Konstantin Rotov (1902–1959) and Boris Efimov (1899–2008), radically differed. Rotov was loved by people for his cheerful drawings but was sentenced under Stalin to fourteen years of prison and exile. Efimov was well treated by a succession of governments, from Lenin to Putin, but although he was the most rewarded Soviet graphic artist of his times, he was never truly popular.1 Neither, however, really chose their destiny: they just tried to survive in difficult times, and in this sense their careers can be seen as exemplary in relation to so many Soviet artists represented in the David King collection within the Tate Library and Archive (from where this article’s illustrations are taken).

Both cartoonists were of humble origin and of roughly similar age. Efimov (his pen-name) was born in 1899 to a Jewish petty trader from Kiev; Rotov was born in 1902 to the family of a provincial carpenter in Rostov-upon-Don. In 1922 Efimov was persuaded by his brother Mikhail, a brilliant publisher and journalist later renowned under the pen-name Koltsov, to come to Moscow and make a living from drawing. In his memoirs Efimov acknowledged that he had been partly inspired by the work of Rotov, who had had his first drawing published as early as 1917, in the satirical journal Bich (A Whip), some months before the October revolution that year.2 In the 1920s both men published their cartoons in many leading journals and newspapers, including Pravda (The Truth), Smekhach (A Jokester), Chudak (A Crank), Krasny Perets (Red Pepper) and, especially, Krokodil (The Crocodile), almost all issues of which are contained in the David King Collection.

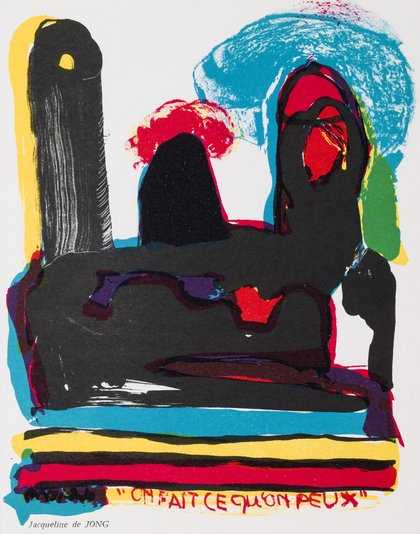

Fig.2

Konstantin Rotov, ‘Traffic in Two Years According to the Promises of Moscow Authorities: So Many Buses and Taxis that a Simple Horse can Startle’, in Krokodil, no.35, 1927, p.12

David King Collection, Tate Archive V DKC Serial Krokodil

Rotov was extremely popular in the interwar years. In the eyes of the general public he was probably the Soviet Union’s most illustrious artist (and was certainly more well-known than such avant-garde artists as Kazimir Malevich, Aleksandr Rodchenko and Marc Chagall). His cartoons appeared on an almost daily basis. Offering a mild and bright humour, they were remembered by people for many years: when Rotov was imprisoned, his fellow inmates would ask him if he had drawn the illustrations for the Golden Calf, an extremely famous satirical novel by his friends I. Il’f and E. Petrov.3 He was especially good at multi-figured scenes which could be pored over for hours, and his style could be compared to that of Walt Disney.

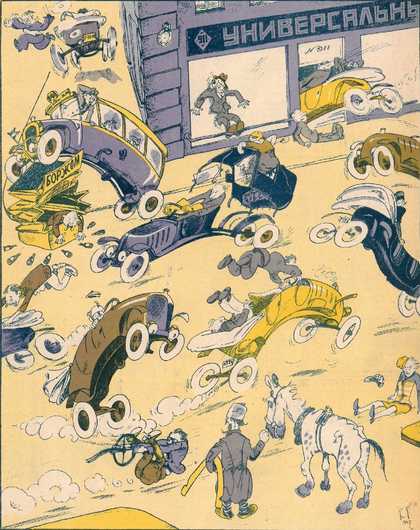

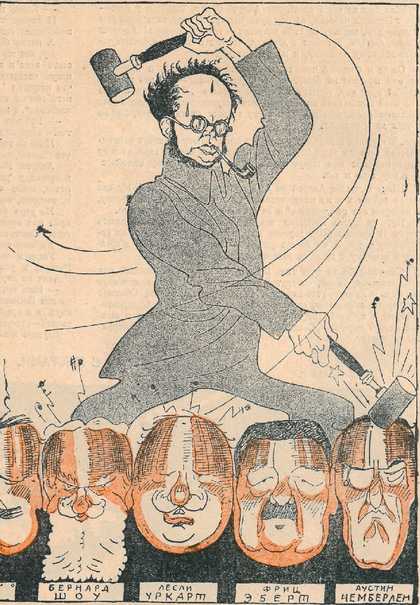

Fig.3

Boris Efimov, ‘Karl Radek Skilfully Plays on the Brass Section Instruments’, published in Krokodil, no.6, 1925, p.5. Radek was an eloquent journalist and one of the leaders of the Komintern. The ‘brasses’ here are heads of foreigner diplomats and moral authorities, including the British statesman Austen Chamberlain and the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw.

David King Collection, Tate Archive V DKC Serial Krokodil

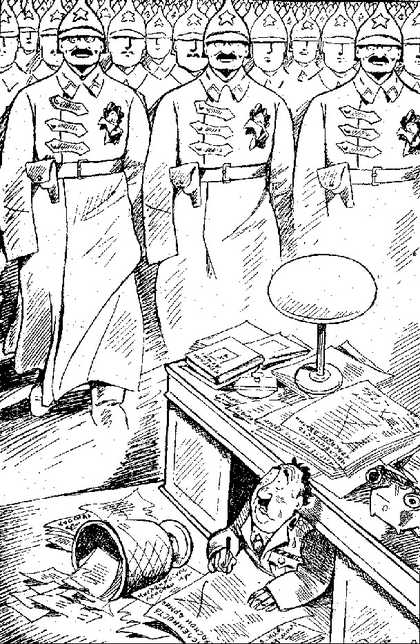

Fig.4

Boris Efimov, ‘British Military Expert Repington is Trying to Define the Exact Size of the Red Army’, in Boris Efimov, Karikatury (Cartoons), Moscow 1924, p.70. Every soldier is shown here with the face of Leon Trotsky, alluding to the fact that he was a founder of Red Army.

David King Collection, Tate Archive id 08115037

Efimov specialised in two genres: one was the so-called ‘friendly caricature’ of Soviet celebrities, mostly unamusing and flattering; the other was harsh or spiteful images. Thanks partly to his brother, he knew many important people, including politicians, publishers and critics, and in 1924 was described by Leon Trotsky, then considered by many Lenin’s heir and a powerful opponent of Stalin, as ‘the most political of our graphic artists’.4 Trotsky wrote the preface to Efimov’s first album of drawings published in 1924 (also in the David King Collection), and the artist repaid him with subtle compliments (fig.4). In 1926 British and Polish governments approved the shooting of four communists in Lithuania, and Efimov published a cartoon showing Austin Chamberlain, the British foreign minister, and the Polish premier Pilsudski applauding the execution. Pilsudski did not react but the British Foreign office issued a diplomatic memorandum to the Soviet Union – something of a coup for Efimov.

By 1929 Stalin had defeated Trotsky in the struggle for control of the Soviet Union. Trotsky was sent into exile and his supporters were arrested and killed. After this other oppositional groups were attacked and, from 1930, Stalin consolidated his power with regular mass repressions. Millions of people were shot or died from starvation and back-breaking toil in labour camps. Political cases were fabricated, trials staged, and groups of ‘enemies of the people’ invented, often centred upon a particular profession or ethnicity (one day the railway workers were punished, the next day genetic scientists, and then the Polish or Romanians, for instance). No independent associations were allowed. All writers were forced into the Writers’ Union, all painters into the Painters’ Union. The profession of the cartoonist became important ideologically and dangerous. By the mid-1930s only one satirical journal, the Krokodil, was permitted to survive.

Fig.5

Konstantin Rotov

Illustration for a short story published in the magazine Prozhektor, no.19, 1928, p.14.

David King Collection, Tate Archive V DKC Serial Prozhektor

Rotov continued to amuse people, producing cartoons that were of day-to-day, bread-and-butter subjects, pungent and cute. He also made illustrations for a number journals, including Ogonek, published by M. Koltsov, Prozhektor and 30 Dnei (all included in the David King Collection). In 1939 a drawing of his provided the source of a large mural in the Soviet Pavilion in the World Exhibition in New York. He also produced some political caricatures, blaming one or another ‘enemy of the people’, but only occasionally and reluctantly.5 In 1940, however, he was arrested for a cartoon titled ‘Closed for Lunch’, depicting a horse and sparrows, made in 1934.6 The joke was Rabelaisian: sparrows were patiently waiting for their lunch (horse’s dung) while a horse was eating something from the nosebag. The hint at the hunger in the USSR was obvious to contemporaries. It had not even been published but a fellow artist reported him to the secret police for it (Rotov later met the same person in prison after the latter also ended up incarcerated). Rotov was charged with ‘defamation of the Soviet trade and cooperation’, tortured and sentenced to eight years in a labour camp.7

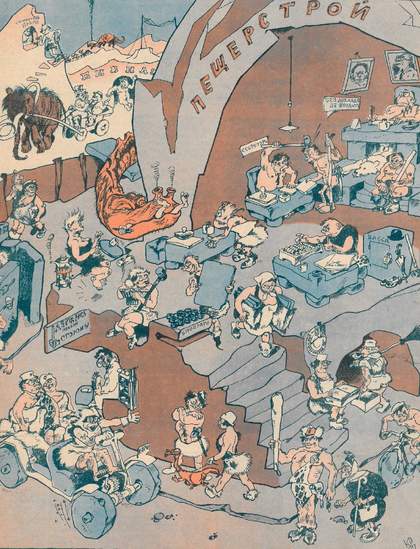

Fig.6

Boris Efimov, ‘Trotsky, Radek and Others Sell their Motherland to the Nazis’, in Boris Efimov, Podzhigateli voiny (Warmongers), Moscow 1938, p.103.

David King Collection, Tate Archive id 08115019

By contrast, Efimov focused on ridiculing ‘enemies of the people’. With his cartoons he skewered the victims of political persecutions, though many were his former contacts and patrons. He attended the Moscow Trials of 1937 and 1938, which crushed the opposition to Stalin, sketching defendants he often knew personally. These included the famous Soviet diplomat Kristian Rakovsky, renowned Troskyite and journalist Karl Radek, and Nikolai Bukharin (another rival of Stalin, semi-official heir to Lenin and Efimov’s direct boss). Sometimes his cartoons appeared on the same day that his subjects were executed. Efimov’s brother Koltsov was arrested in 1938 and executed two years later, and he himself expected to be arrested, but his reputation within the regime saved him: Stalin personally forbade anyone to hurt him because he was useful. Naturally, Efimov could never refuse to undertake work in support of the regime.

Fig.7

Boris Efimov, ‘The Ideal Aryan should be Tall, Slim and Blonde’, in Boris Efimov, Hitler and his Gang, London, 1943, p.15.

David King Collection, Tate Archive id 08094344

Throughout the war years he specialised in drawing Hitler and the Nazis, images that proved very popular among front line soldiers.[i] Efimov was awarded the most prestigious honours, including several ‘Stalin prizes’ and ‘State prizes’, an ‘Order of Lenin’ and an ‘Order of the Red Banner’. He became the most lauded cartoonist in the entire Soviet Union and, probably, the most well-off artist. Albums of his caricatures were printed in millions of copies in the USSR and abroad (see fig.7).

During his years in a labour camp, Rotov was respected by not only fellow-prisoners but also by the camp administrators. His camp manufactured toys (largely rabbits and bears) designed by Rotov, and for the authorities he made copies of well-known nineteenth-century Russian paintings. When his term in the camp came to an end, he was sentenced again, this time to exile in Siberia; he was able to return to Moscow only in 1954, after the death of Stalin. He immediately resumed drawing, producing illustrations for fairy tales and fantastical stories, such as Adventures of Captain Vrungel or Old Man Khottabych. These became (and still are) very popular, although few remembered his name and past fame. He died in 1959, his health having been damaged during his years of imprisonment.

Efimov died in 2008, at the age of 108. During his long life he made more than 700,000 pictures, and until his very last years he continued to attack various ‘enemies of the state’. When asked how he managed to live for so long, he sadly answered, ‘I don't know. Maybe, I have lived two lives, one of them for my brother.’

The David King Collection (TGA 20172) and David King Library Special Collection (DKC) are available to consult at the Tate Library and Archive, Tate Britain.