Why did you select this work for the project?

I confess I’ve been an Anselm Kiefer fan for a long time, and had written about his woodcuts and paintings, but I didn’t know so much about his photographic work. While I knew about the infamous photographic essay, ‘Occupations’, I was curious to discover more about the Heroic Symbols photographs in the ARTIST ROOMS collection.

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

© Anselm Kiefer

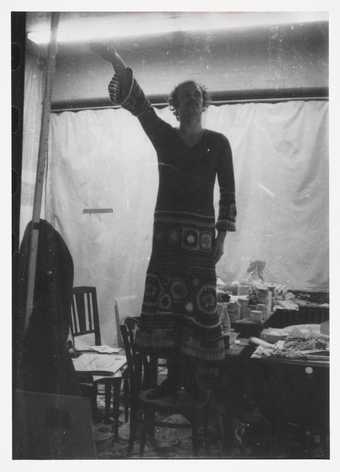

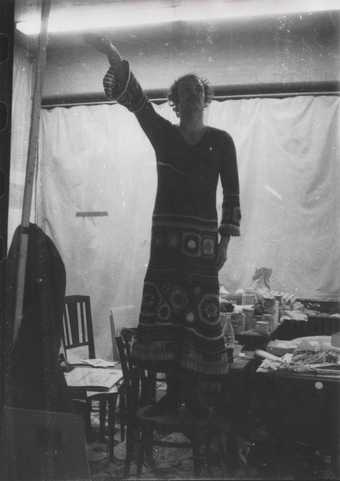

The ones taken at various European locations seemed, to me, like a dangerous subversion of an Interrail holiday. I made a number of those European tours in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and here was Kiefer travelling to all these locations and giving the taboo Sieg Heil gesture, at a particularly sensitive time in the 1960s. I admired his bravado, especially as he was probably well aware of the misunderstandings that would inevitably ensue as a result of showing the work.

I was also drawn to ‘Occupations’ because it brought about the downfall of the magazine Interfunktionen in 1975. The art critic Benjamin Buchloh was then editor of the magazine, and he started off as a great champion of Kiefer’s work and it was only later, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, that he turned against much of what Kiefer was doing. But certainly these early works – what Buchloh has called Kiefer’s dialogue with ‘photo conceptualism’ – impressed him a great deal. So I was curious to know more about the collapse of the magazine and the circumstances around that.

How did you go about researching this work?

My longstanding interest in Kiefer became more focussed when the Royal Academy of Arts asked me to contribute an extended catalogue essay for their major 2014 retrospective. I revisited literature I’d read previously, and read more on the artist to build up as comprehensive a picture as possible, and to provide a context for the photographs. It was also important for me to correspond with other Kiefer experts, such as Matthew Biro, and also his earliest critics, for instance Eckhart Gillen, who was the first art critic to ever write a review of a Kiefer exhibition in February 1970. I was also fortunate to interview Georg Baselitz in 2014, which provided me with invaluable insights into Kiefer’s early career, when the two artists were close friends.

Christian Weikop

Self-portrait in the glass of an Anselm Kiefer vitrine installation, Royal Academy of Arts courtyard 2014

The great advantage was being able to interview Kiefer in person, at his vast studio complex in Croissy-Beaubourg, on the outskirts of Paris. I was there as an envoy of the RA, but I took the opportunity to ask Anselm questions related to the Tate In Focus project as well. We spent several hours together and he was very generous in his responses. He also gave me unrestricted access to his studio, which was a great privilege. There I could see directly just how important these early photographs were, as they were still being utilised in installations and as models for paintings being worked on in his studio spaces. The sheer extent of it was a revelation: the images appear, almost ghost-like, across a number of artworks. In this respect, he seems attracted to Friedrich Nietzsche’s idea of eternal recurrence, and the work has a particular resonance today, if you consider the spectre of fascism destabilising Europe.

Is there a balance to maintain when incorporating an artist’s voice into a research project?

It’s always a risky business. Take another great German artist, the Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, for example: he very much manipulated the media and his own historical interpretation: he back-dated paintings and prints and even invented a French pseudonym, Louis de Marsalle, to write celebratory articles about his own work in various art magazines. I’m conscious of these issues and have written about the validity of artist statements in my academic work, but still there is no substitute for interviewing a living artist directly and asking about their original intentions. With a very intellectual artist like Kiefer you can learn a lot about his making processes and ideas. He also welcomes multiple ways of seeing his work, and there was no sense that he was attempting to close down interpretation.

The series includes hundreds of images. How did you narrow down the selection?

Originally I was working with just six photographs from the ARTIST ROOMS collection, so in fact it was a case of finding a wider context for the work, rather than narrowing it down. At the beginning, I didn’t realise the full extent of the number of photographs he’d taken back in 1969. Many of those negatives weren’t developed at all, until he discovered them when moving his studio from Barjac, in the south of France, to Paris in 2007. He was then able to create more work from negatives that had never been used.

Did you find yourself desensitised to the imagery through this process of intense study?

These images look shocking at first sight, and I can understand the shock value they had when first published in 1975, but when you look more closely you see that Kiefer is often wearing a crocheted dress, or a loose fitting suit and aviator sunglasses, or some other outfit that makes the action rather absurd. As I point out in the project, at no moment does he look like a fully signed-up member of the National Socialist Party. In fact, he more often looks rather dishevelled, like an unkempt hippie. That visual contradiction is intriguing.

How does your research inform the way the works are viewed today?

Given the scale of the project, my hope is that the subtle nuances and complexities of what Kiefer was trying to do come to the fore. In many respects, he was attempting to deconstruct his own history, rather than presenting uncritically a gesture that is associated with fascism, which is how some critics wrongly interpreted the work at the time which contributed to Kiefer being marginalised in some quarters of the art world.

What have you particularly enjoyed about working on this In Focus project?

The collaborative aspect of the In Focus series is great and I was delighted to work with Lara Day and Hannah Abdullah and obtain their perspectives. I very much enjoyed working with the Kiefer studio and having the opportunity to ask the artist questions in interview. Being able to draw on the Tate collection in order to provide a wider visual context for the work was very important, for example taking the work from Andy Warhol’s Mao Tse-Tung series and relating that to Kiefer’s work. In many ways, Tate’s In Focus series is a great innovation.