When Greg Sullivan and I began to think about the Family Matters display we were excited at the opportunity to explore changing ideas about the family over the centuries and hang contemporary works alongside historic art. Bringing the many strands of the show together in a coherent hang was a challenge – how were we to exhibit contemporary photographs, archive photo albums, public submission photographs, oil paintings, sculpture and video art alongside each other in a way that did them all justice?

In addition, the show, which originated in Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, had travelled to two other venues before reaching us, where it was displayed over several rooms. With only one large room for our version of the exhibition, the first task – carried out by our colleague Tabitha Barber- was to edit down the hang while trying to retain the spirit and complexity of its original conception. Our solution was to try and pair works of art and draw attention to connections and disjunctures between them.

In some instances, works spoke to each other visually, such as David Hockney’s My Parents and Henry Walton’s Sir Robert and Lady Buxton and their daughter Anne, which both explore ideas around parenthood. In the Hockney, mother and father are passively observed by their son; the father left to peruse his book uninterrupted. In Walton’s painting, the daughter interrupts her parent’s reading and demands to be included. Equally, by hanging Martin Parr’s The Last Resort (1983-6) next to Johan Zoffany’s The Bradshaw Family (1769) Parr’s modern scene of a family eating chips is recast in the light of traditional family portraiture and begins to reveal many of the same compositional devices as its eighteenth-century counterpart.

In other cases, the links were more conceptual. Donald Rodney’s In the House of my Father (1996-7) shows the artist’s hand holding a small house made of skin, which was removed during an operation to combat sickle-cell anaemia, an hereditary disease. Engaging with ideas of inheritance, it is paired with Robert Braithwaite Martineau’s The Last Day in the Old Home (1862) in which a father who has squandered all his money is forced to sell the family house. Lot numbers are visible on all the paintings and furniture and the grandmother weeps to the left of the scene but the father, oblivious to the pain he has caused, appears to be pointing his son on a similar path as they sample wines to the right of the picture.

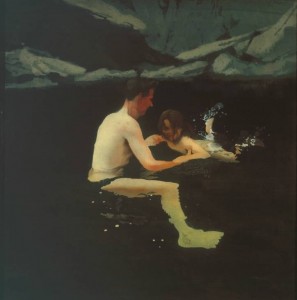

Responding to public feedback in relation to the taster display for this show, mounted in the gallery earlier in the year, we also wanted to reflect the complexity of families. While some of the works on show, for example Michael Andrews’ tender portrait Melanie and Me Swimming (1978-9) revealed the support and love families can offer, we also wanted to acknowledge their more difficult side. Bill Brandt’s photographs A Sheffield Backyard (1936) and Parlourmaid and Undermaid ready to serve dinner (1936) show two very different experiences of British family life; a bleak urban backyard revealing the underbelly of industrial Britain contrasted with the cut glass and silverware of an upper class dining table.

The final element of the display, which really drew all the strands together, was the inclusion of photographs sent in by members of the public in response to the question ‘What does family mean to you? The images we chose to display, in a showcase opposite a group of Vanessa Bell family albums from the Tate Archive, found resonances in a number of the works hanging on the walls around them and helped to illustrate the highly varied nature of the modern British family.

Now that the show has been installed, we hope it will encourage visitors to think again about family life; what it means to them and what it has meant for previous generations.Family Matters: The Family in British Art opens today at Tate Britain and runs until 24th February 2013.

Written by Ruth Kenny, Assistant Curator 1750-1830

![Karl-Stephen Obulo [karlobulo@googlemail.com]](../wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Karl-Stephen-Obulo-karlobulo@googlemail.com_-300x300.jpg)

What does art mean to you?

You can also join the debate on

Facebook

Twitter

Youtube