The terms ‘visual language’ or ‘vocabulary’ are typically used to describe the distinct characteristics of an artist’s practice. This employment of words is apt within the context of modern and contemporary art, since the use of written or spoken word has been a significant feature of artists’ practices since the early twentieth century. The use of letters and words in artworks is traditionally associated with authorship – the artist’s signature or inscription, often towards bottom of a painting or drawing.

Works form the early twentieth century where appropriated words, letters and symbols were increasingly incorporated, such as Francis Picabia’s The Fig-Leaf1922 and Kurt Schwitters’s Mz.299 1922, reflected the emerging avant-garde movements of the time. This period also saw an increasing presence of the printed word in the urban landscape and the developing sophistication of marketing and advertising.

Picabia, Schwitters and Marcel Duchamp were all associated with the dada movement and rejected traditional art materials, processes and subjects through the appropriation of found objects, known as ready-mades. In Duchamp’s seminal work Fountain 1917, replica 1964, he incorporates the name R. Mutt. Here he uses text in its traditional sense by indicating authorship; however R. Mutt is the name of the factious artist -Duchamp’s pseudonym. This controversial work questioned the identity of the artist through the incorporation of text while the nature of its creation brought into the question the role of the artist and the object.

By the time Duchamp had created Fountain he had already defined ‘the artist’ as someone able to rethink the world and remake meaning through language. While Duchamp paved the way for conceptual artists it was Sol LeWitt who first coin the term ‘conceptual art’ in the article Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, 1967. LeWitt, along with the text-based artists Joseph Kosuth, Art & Language, Hamish Fulton and Richard Long, represented a fundamental strand in the conceptual art movement. Text and language became a crucial vehicle for artists challenging the notion that an artwork should consist of a physical object. In the late 1960s and early 1970s conceptual art was established as a category or movement and language was a central concern for artists such as Ed Ruscha and Lawrence Weiner.

Conceptual art represented a shift towards ideas and systems that invited the viewer to engage with an intellectual concept, art became increasingly ephemeral and transient - famously described by Duchamp as the “dematerialisation of the art object”. Lawrence Weiner’s use of language and words focuses on the interaction between the artwork and the ‘receiver’ – the audience who encounters the work in some form. His ‘statements’, which then have the potential to be inscribed as a written text on a gallery wall (or any other wall for that matter), spoken as dialogue on a video, printed in a book or poster, sung, or even tattooed onto the skin.

The Weiner works in the ARTIST ROOMS collection consist of a cycle of ten wall texts; each statement such as Tied Up in Knots 1988 and Roughly Ripped Apart1988 suggests a physical action or invoke the manipulation of an object or matter. Weiner regards his language works as sculptures, and they can be seen as instructions or propositions that could be enacted. These works are displayed as vinyl lettering applied directly to the exhibition surface. The artist’s aim is to offer a universal, objective experience in which the reader is invited to execute the work through his or her own imagination.

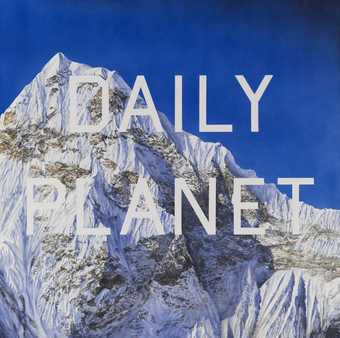

The work of Ed Ruscha is equally associated with conceptual art. Ruscha, however, is also associated with pop art and the printed word from mass media and advertising was evident in his work as he drew on popular culture. Ruscha looked at words as graphic signs in their own right. “The words have these abstract shapes, they live in a world of no size,” noted Ed Ruscha in relation to his early single word-works which often employ visual alliteration. Ruscha’s later drawings of pithy phrases resonate with the work of Weiner’s; Ruscha’s texts however do not suggest a physical action but are often a humorous reflection on American culture. Works such as DIRTY BABY 1977 evoke American vernacular and slang, draw attention to a particular experience of the artist, or recall the excesses of Hollywood culture.

Bruce Nauman’s colourful neon text-pieces are frequently self-referential and equally as playful as Ruscha’s paintings and prints. The neon sculpture La Brea/Art Tips/Rat Spit/Tar Pits 1972 consists of phrases progressing in a circle, indicating a process of thought which the anagrams for the La Brea Tar Pits come from. The work was originally created for the 1972 retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Nauman proposed an outdoor work that would encircle the walls of the museum, which stands adjacent to a famous prehistoric site, La Brea Tar Pits. The piece included the name of the site along with two anagrams of these four words depicted in neon tubing. This work is an indoor version that Nauman made in the same year. Throughout the early 1970s Nauman created several more luminous signs that used a combination of witty word games and bold colour to disturb the meaning of everyday phrases and expressions.

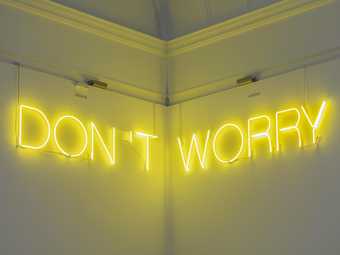

Like the earlier generation of LeWitt and Weiner, Martin Creed is often referred to as a conceptual artist in the minimalist tradition. In Work No. 890 (DON’T WORRY)2008, the words ‘don’t’ and ‘worry’, appearing in upper-case, sit adjacent to one another at a right angle in yellow neon. With a wry sense of humour Creed uses language to unsettle and amuse – both words are always apparent to the viewer yet need one another to comfort.

The Italian artist Mario Merz began using neon in 1966, his neon texts were often juxtaposed against everyday objects as is the case with Che Fare? 1968-73. The words ‘Che Fare’ in neon resemble handwriting sunk into a pot of wax that melts under the heat of the neon. Che Fare translates as ‘What is to be Done?’ taken from the title of a political pamphlet produced by Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin in 1902. The text is widely regarded as advocating a political party to promote Marxism within the working classes and has come to define the drama of an individual’s engagement in modern society.

This critical reflection on modern society is also evident in Jenny Holzer’s work through her witty and provocative slogans which reference to everyday experiences and emotions. BLUE PURPLE TILT 1996 collates messages from the artist’s career, charting her development from the early Truisms and Survival series, including pithy texts such as “PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT”, through to the anonymous declarations of the Inflammatory Essay and personal musings of Lamentations. Seven luminous LED signs are used to transmit her texts, emanating brightly and enveloping the viewer. The staging of her messages is central to Holzer’s practice, and serves to emphasise how language shapes our cultural environments.

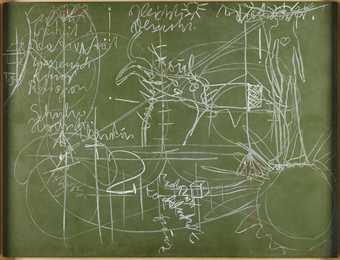

While Holzer is known for inserting her political statements into the public sphere, the German artist Joseph Beuys is lauded for his role using art for social transformation. Beuys positioned himself as artist, teacher and educator often articulating his thinking through extensive lectures, using blackboards to illustrate his ideas in works such as For the lecture: The social organism - a work of art, Bochum, 2nd March 1974 1974. Beuys own words were inextricably linked with the artwork itself in part because of his role as a teacher and activist.

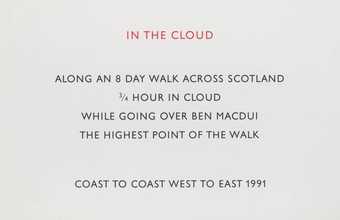

Much of Beuys’s work was focused on the environment - many of actions would take place in the landscape. Richard Long also has an affinity with nature and his work, which is often a documentation of his walks in the landscape, is about his interaction with the environment. While some of Richard Long’s walks are recorded by a photograph others, such as In the Clouds 1991 are text based. These pieces are sparse in nature, with a handful of words chosen to describe the long walks the artist makes all over the world.

Artists have, of course, also looked to language for its poetic impact and literary resonances. Concrete poets, including Ian Hamilton Finlay, explored the formal qualities of language through its visual arrangement on a page, creating sculptural works with embedded text. In the work Sailing Dinghy 1996 Finlay brings a sailing boat together with corresponding text and symbols, which resonate with an imagined sea journey on the vessel. Finlay was also drawn to how language shapes the world in which we live and his sculptural works entwine references to nature, the Romantic sublime and history through a combination of deftly chosen objects, poems and sentences. The garden Little Sparta, perhaps his tour de force creation, in the Pentland Hills near Edinburgh is littered with aphorisms, poems and references to ancient Greece and particularly the rivalry between Athens and Sparta. The garden was named in acknowledgement of Edinburgh’s nickname, ‘the Athens of the North’.

Like Finlay, Cy Twombly was equally fascinated and inspired by Mediterranean heritage. Twombly first travelled to Italy and North Africa in the early 1950s and settled there in 1957. Throughout his career Twombly referenceed classic literature and mythology, while blurring the lines between painting and writing. Twombly’s distinctive style often encompassed scrawled text and motifs reminiscent of both the primitive and classical, which is evident in works such as Souvenir de L’Ile des Saintes 1979.