Artists often explore the characteristics that determine our personal and social identity. They construct a sense of who we are as individuals, as a society, or as a nation. They question stereotypes and conventions while exploring attributes such as gender, sexuality, race, nationality and heritage. Our culture is informed by various forms of artistic and social endeavour such as technology, politics, style, music, performance and the arts. ‘Cultural studies’ emerged in the late 1950s and has been informed by radical approaches such as Marxism, feminism and semiotics.

The period of the Weimar Republic 1919–33 was a time of immense cultural revival in Germany. Berlin was the nerve centre of this activity and art forms such as cinema, dance, literature, theatre and visual arts all thrived. The mood of the time was famously captured by Christopher Isherwood’s novel Goodbye Berlin, its decadence and political upheaval were depicted in the paintings of the Neue Sachlichkeit artists such as Otto Dix and Geog Grosz. Dix, like many artists of the time, was a subject of the Weimar photographer August Sander, who photographed individuals and groups of people that he then classified according to their occupations and position in society. Amongst these categories were The Skilled Tradesman, which included iconic portraits such as Bricklayer 1928 and Pastry Cook 1928.

This lifelong attempt to document the German people resulted in Sander’s exhaustive portfolio People of the 20th Century which presented a diverse and democratic society. This vision was at odds with the emerging totalitarian regime which marked the end of the Weimar Republic and Sander’s publication Face of Our Time 1929 was subsequently confiscated and destroyed by the Nazi government in 1934. Sander is recognised as a major force in the history of photography. His work was an enormous influence on a later generation of photographers such as Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon and Walker Evans.

While Sander was known for his range of subjects, Diane Arbus was known for photographing those on the margins of society. New York born Arbus came to prominence in the New Documents exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1967, along with Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand. The exhibition heralded a new generation of photographers. The exhibition’s curator noted that they “directed the documentary approach towards more personal end…Their aim has been not to reform life, but to know it.” New York in the 1960s, like the Weimar Republic of 1920s, was a richly diverse society and attracted artists and political dissidents. During this period cultural politics were at the fore; minority groups such as the Black Panthers challenged authority through protest while the repression of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender communities culminated in the Stonewall riots of 1969.

Arbus’ interest and celebration of gender and identity is evident in images such as Two Friends at Home, N.Y.C. 1965 1965 where a couple are photographed in their domestic setting, creating an intimate portrait suggestive of the nature of their relationship. Arbus’ direct images convey a sense of trust between the sitter and the artist where strikingly and often brutal portraits convey inner emotions.

“There are and have been and will be an infinite number of things on earth. Individuals, all different, all wanting different things, all looking different. Everything that has been on earth has been different from every other thing. That is what I love: the differences, the uniqueness of all things and the importance of life… I see something that seems wonderful; I see the divineness in ordinary things.”

Another New York-based photographer was the artist Robert Mapplethorpe whose images, like Arbus, convey a sense of trust and honesty. Mapplethorpe, who primarily worked in the studio, came to prominence in the mid-1970s with portraits of his inner circle of friends and acquaintances, including artists, composers, and socialites. Unlike Arbus, Mapplethorpe used himself as a subject, returning to the self portrait throughout his career.

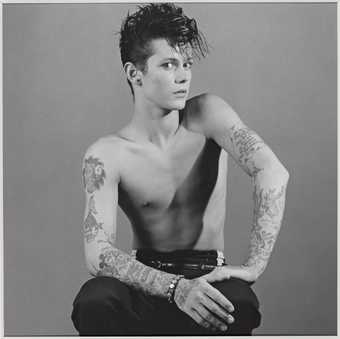

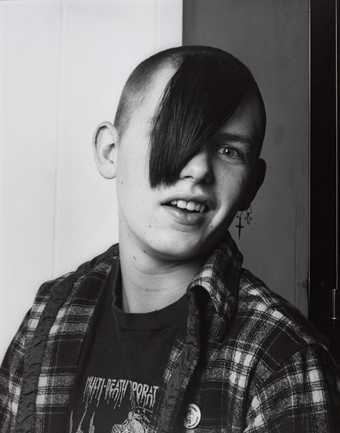

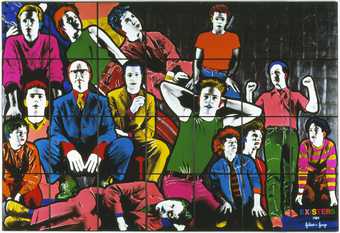

Mapplethorpe’s oeuvre included photographic portraits, still lives and nudes. He was also known for his sexually explicit images, which depicted the underground gay S&M scene of the mid-1970s. In these controversial works, sexuality takes precedence over social class or distinction of the sitter: examples of this include unknown young men such as Smutty 1980 and Tattoo Artist’s Son 1984. The British artists Gilbert & George began to photograph casts of young men from London’s East End in the early 1980s. Although works such as Existers 1984 are somewhat ambiguous the young men are elevated to the status of icon through their embodied potency, strength and beauty, the use of photographic panels resembling stained glass windows. Such depictions of young men aroused considerable hostility among critics, who accused Gilbert & George of being exploitative, and wrongly described the youths as rent boys or East End thugs.

Gilbert & George explored their own identity working as a pair and presenting themselves as ‘living sculpture’, incorporating themselves and their lives into their art, they set out to provoke their viewers, to make them think and question conventions and social taboos. Bruce Nauman, like Gilbert & George, was associated with conceptual and performance art in the 1970s. Nauman is renowned for his investigation into the human condition through language and the human body. “My work comes out of being frustrated about the human condition. And about how people refuse to understand other people.”

Nauman blurred the boundaries between performance and installation art in the 1970s with works that encouraged the spectator to become participant. His work often incorporates tools of mass media e.g. televisions and neon lettering, while challenging their conventions. Nauman’s video works, which are at times both ambiguous and menacing, are metaphors for the rituals, gestures and struggles of daily human existence. In works such as Setting a Good Corner (Allegory and Metaphor) 1999, Nauman documents his everyday life, where his identity as an individual is informed by ‘place’ and occupation. The menacing nature of the works concern questions of anxiety and alienation. Whilst not ‘overtly’ a political artist Nauman’s work often references the political cultural climate of the late-twentieth and early twenty-first century.

In the late 1970s, Jenny Holzer devised slogans known as Truisms 1977-9, which play on commonly held truths and clichés. A truism is a statement which is obviously true and says nothing new or interesting: A LITTLE KNOWLEDGE CANGO A LONG WAY. Initially, the Truisms were infiltrated into the public arena via stickers, T-shirts and posters. Later, Holzer started using electronic displays. In 1982 she emblazoned these messages across a giant advertising hoarding in Times Square, New York. The Truisms are deliberately challenging, presenting a spectrum of often-contradictory opinions. Holzer hoped they would sharpen people’s awareness of the ‘usual baloney they are fed’ in daily life.

Protect Protect 2007 forms part of a series of screenprints that reveal sensitive government transcripts relating to America’s intervention in the Middle East. Here Holzer uses a document from the National Security Archive, enlarging a military map and setting it upon a bright background. Holzer’s technique forces us to acknowledge the interpretative power of language, where the words “protect”, “suppress” and “isolate” emanate strongly against the image of a deeply divided and segregated Iraq.

Like Holzer, the work of Belgian artist Johan Grimonprez can be read as a political comment on contemporary culture while asking questions. Grimonprez came to prominence when this film-essay, Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y + Inflight 1997-2001, was shown in 1997 at Documenta X. The work sees the protagonists perform a series of rituals at airports where identity is to some extent removed, taking off items of clothing while being security cleared and saying goodbye to loved ones. The work traces the history of airplane hijackings, eerily foreshadowing the events of 9/11, through archival images discovered during thorough research, televised images and quirky home movies.

As Grimonprez uses pre-existing film to collage an artwork, Gerhard Richter used photographs of eminent scientists, writers, musicians and philosophers found in encyclopaedia and dictionaries for his 1972 work 48 Portraits. The figures, such as the writer Franz Kafka, the composer Igor Stravinsky and the scientist Isidor Issac Rabi, are all European and North American men. Although they broadly represent a humanistic view of Western civilisation in the nineteenth and early twentieth century they do prompt the question of which cultural figures are used to compose history. There are no women, religious figures or prominent persons from out with Western society. One of four photographic editions of 48 Portraits 1971-98 is held in the ARTIST ROOMS collection.

Andy Warhol’s celebrity portraits and films often incorporated those from his social scene, including his associates from his studio, The Factory. The celebrities and factory stars of these artworks such as Liz 1965 are not just a celebration of celebrity but are tinged with tragedy, especially the images of women such as Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe and Jacqueline Kennedy. The stars themselves were often associated with misfortune and the works both pre-empt the obsessive nature of celebrity and reflect on the negative connotations of life in the public eye. His society portraits, like those of Mapplethorpe, represent not just the society that he himself inhabited but also wider popular culture and many subcultures.

The polaroid, A Self-Portrait with Fright Wig 1986, is one of several that Warhol took in preparation for a series of large-scale paintings commissioned by Anthony d’Offay for an exhibition at his London gallery in 1986. In the photographs, and subsequently transferred into the paintings, Warhol’s skull-like head is isolated from his body, floating against a dark background. This composition bears striking similarities to a Robert Mapplethorpe photographic portrait of Warhol from the same year. In both, Warhol wears his famous silver wig, but, in this Polaroid, the hair stands on end in an almost manic fashion. His eyes seem to be fixated on something to the left, behind the viewer, creating a distinct feeling of uneasiness. This series of self-portraits was the last Warhol completed before his death in 1987.

Richter and Grimonprez appropriate objects and images into their artwork to construct identities as does Ellen Gallagher, much of whose work is informed by her Irish and African-American heritage. Gallagher’s paintings and mixed media collages often question racial stereotypes and appropriate references to the physical divisions in race.

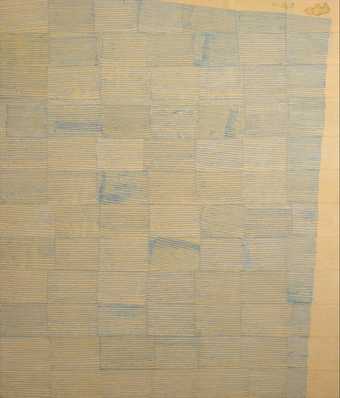

Paper Cup 1996 is part of Gallagher’s first mature body of work which explored layered and contradictory themes. Gallagher has created a loosely structured grid by lining up small pieces of writing paper in multiple rows, recalling the history of handwriting exercises. Closer inspection reveals each line to be carefully constructed from rows of bulbous shapes resembling the vowels a child must repeat when learning to write, though they are in fact a reference to the stereotypical lips of American blackface minstrels. From a distance this large work’s subtle geometry resembles an American minimalist painting, but closer inspection reveals not only a darker side of American history but references Gallagher’s own mixed-race origins.