What is a ritual? Rituals can be religious, ceremonial or personal; they can be represented directly or referred to symbolically using imagery, objects or abstract shapes and patterns.

What is a ritual?

A ritual is a an activity that usually sticks to a set pattern and typically involves a set of actions, words, and objects. Rituals are often repeated at intervals (whether daily, weekly, annually – or on certain special occasions). The word ritual often has associations of serious formal or religious ceremonies – like graduations, christenings or processions – but a ritual can also relate to cultural activities or traditions that happen in everyday life such as Christmas shopping or carnivals…or even fish and chips on a Friday. A ritual can also be highly personal: Do you always play football or swim on a Saturday morning or have tea at your grannies every Sunday? These could be considered your personal rituals.

Ceremonies, processions and celebrations

Paula Rego

The Dance (1988)

Tate

Some artists choose to capture the traditional solemnity of ritual. William Blake’s funeral procession has a moving simplicity in its rhythmic repetition of figures. Sonia Boyce in her painting Missionary Position II uses the ritual of prayer to symbolize conflicting opinions about religious beliefs across different generations and cultures in British society. Other artists have explored the often eerie or magical quality of ritual. Paula Rego’s dancers on a beach seem to be taking part in some mysterious, secret ceremonial dance. Edward Burra often combines macabre imagery with humour. There is a certain carnival spirit to his Dancing Skeletons which perhaps reference the Mexican Day of the Dead festival when families and friends gather to remember and celebrate the lives of relatives who have died.

Personal and everyday rituals

Jeremy Deller, Alan Kane

Souped Up Tea Urn & Teapot (Dartford 2004) (2004)

Tate

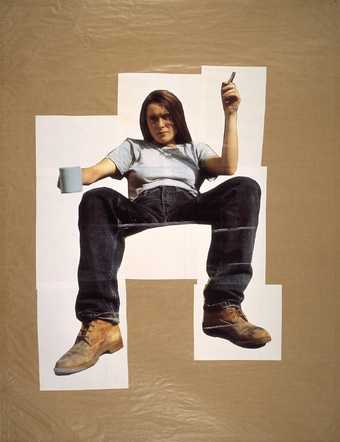

Ritual ceremonies don’t have to be big grand statements or involve lots of people. They can be personal and private. In Fikret Atay’s video Rebels of the Dance two boys dance in a small lobby housing an ATM. They perform their version of traditional Kurdish dances in their own personal ritual. Everyday habits can become ritualistic if the same actions, words, and objects are involved. Cecil Collins depicts the ritual of daily afternoon tea in The Artist and His Wife ‘sitting opposite each other like high priests’. In fact tea drinking generally is often presented by British artists with ritualistic significance. Serving and drinking tea – out of a souped up tea urn – becomes an art happening in artist Jeremy Deller’s hands; while Sarah Lucas photographs herself drinking tea in one of early her self-portraits exploring her identity.

Objects

Ritual as a theme in art doesn’t always show a ritual actually happening. Artists often reference ritual through objects or materials.

The brightly coloured powder that gives Anish Kapoor’s sculptures their mysterious mystical quality is pure pigment – a substance associated with ritual ceremonies in India. Rasheed Araeen’s Bismullah explores his identity as a Muslim in British society through photographs which reference Islamic ritual.

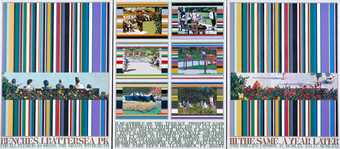

Rasheed Araeen

Bismullah (1988)

Tate

Masks are also objects often associated with ritual. Henry Moore’s Mask has an ancient tribal quality; while Rebecca Horn’s masks, headdresses and costumes look as if they are made for an elaborate ritualistic performance.

Henry Moore OM, CH

Mask (1929)

Tate

Rebecca Horn

Pencil Mask (1972)

Tate

Cornelia Parker’s installation Thirty Pieces of Silver is made up of silver objects often associated with commemorative rituals marking important events in people’s lives – such as christenings, weddings or turning twenty-one. But Parker has systematically crushed the objects using a steamroller and suspended them from the gallery ceiling to create a striking installation. As well as the silver itself having ritualistic associations, the act of crushing the objects is something Parker returns to again and again in her works – making this act in itself rather like a ritualistic performance. By flattening the objects she questions and changes their meaning.

Shapes and patterns

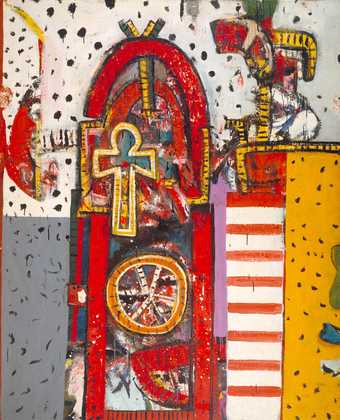

Alan Davie

Fairy Tree No. 5 (1971)

Tate

Shapes and patterns associated with ritual are also found in art. Many people have Celtic tattoos based on patterns found on ceremonial objects from ancient Celtic culture and religion. Richard Wright’s Untitled Figure 3 is an abstract pattern inspired by tattoo and biker-jacket motifs, patterns found on medieval manuscripts, and gothic and baroque religious architectural decoration. Artist Alan Davie created a whole language of abstract symbols and shapes which he derived from emblems and signs associated with Zen Buddhism and magic.

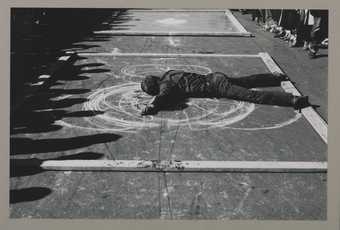

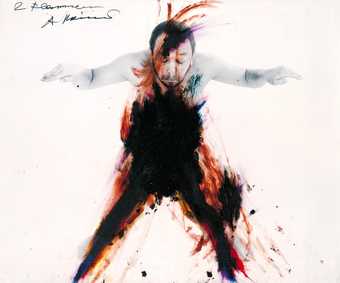

Performance art as ritual

Artists’ performance often has a ritualistic quality – as artists create and use their own personal mythologies in order to explore their identity and wider society. Mona Hatoumused her own body as a site for exploring the fragility and strength of the human condition under duress. For the 1985 Roadworks exhibition organised by the Brixton Artists Collective, Hatoum walked barefoot through the streets of Brixton in London for nearly an hour with Doc Marten boots, usually worn by both police and skinheads, attached to her ankles by their laces. This act, captured in Performance Still 1985, is reminiscent of religious pilgrimages where pilgrims endure extreme hardship to demonstrate their belief and faith. Artist Joseph Beuys’s interest in mythology, botany and zoology led him to evolve a rich and complex personal symbolism. To Beuys fat and felt were important symbols of life and survival and he often incorporated these into his performances.