Turner Bequest CCCLVI 1–24

Roll sketchbook with dark green-grey paper covers and cloth spine

Inscribed by Turner in ink ‘24 Ideas of Folkestone’ towards top centre of front cover

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram towards bottom right of inside back cover

Stamped in black ‘CCCLVI’ top centre of front cover

Inscribed in pencil ‘CCCLVI’ top centre and bottom right on front cover, and in pencil ‘schedule 3.’ towards top left

24 leaves of white wove paper with front and rear paste-downs of similar paper

Approximate page size 230 x 328 mm

Inscribed by Turner in ink ‘24 Ideas of Folkestone’ towards top centre of front cover

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram towards bottom right of inside back cover

Stamped in black ‘CCCLVI’ top centre of front cover

Inscribed in pencil ‘CCCLVI’ top centre and bottom right on front cover, and in pencil ‘schedule 3.’ towards top left

24 leaves of white wove paper with front and rear paste-downs of similar paper

Approximate page size 230 x 328 mm

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

Ideas of Folkestone is typical of the soft-covered ‘roll’ sketchbooks favoured by Turner during his late travels; so called, as curator Robert Upstone writes, ‘because they could be rolled up and stored in a pocket’.1 Horizontal in format, the sketchbook is comprised of dark green-grey thick paper covers with a dark green cloth spine. It is generally believed that the ink inscription on the front cover of the sketchbook, ‘Ideas of Folkestone’, is in Turner’s hand. Tate curator David Blayney Brown notes that ‘unlike some sketchbooks of this period’ Ideas of Folkestone was ‘left intact by Ruskin, whose endorsement it bears’.2

The drawings are in watercolour, some with light and often minimal pencil under-sketches. Of Turner’s methods in this medium, Upstone notes that the artist either made his initial sketch on the spot, the ‘watercolour being applied directly onto a roll sketchbook sheet’, or he later transferred ‘the visual information from one of his smaller books, or from one of the pieces of loose paper he carried’.3 In this sketchbook the drawings have been taken ‘sometimes, but not necessarily always ... on the spot’, according to Brown.4 Some of them may have been produced at Turner’s lodgings following a day’s sketching; various memories, pictorial jottings, and annotations on colours or effects later synthesised to produce a view.

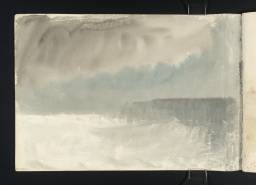

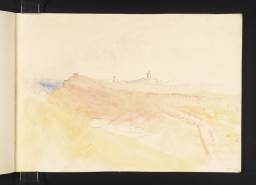

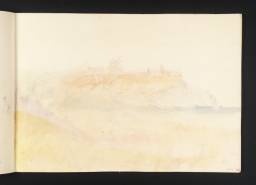

The sketchbook begins and ends with two drawings of Folkestone harbour pier in stormy weather on the inside front and back covers (D35361, D35385). Rendered in pure watercolour, the paper has been flooded with broad applications of blue and sombre grey wash. The rest of the sketchbook is comprised of beach and harbour scenes often with views of the coastal headlands receding into the distance. Local features such as the Pent Stream (D35362), the thirteenth-century Church of St Mary and St Eanswythe (D35370), and Folkestone’s Foord railway viaduct appear in a number of the sheets (D35371–D35374). The last of these features appears to have been of particular interest to Turner given that he took multiple views of the viaduct from various angles, rendering it each time with a vivid red pigment probably to capture the brightness of the new red brick. Built in 1844, only one year before the Ideas of Folkestone drawings were taken, the viaduct was constructed for a branch line connecting Folkestone Junction station with a new harbour station. The line was primarily for passengers taking steamer packets to Boulogne on the northern French coast.5

Indeed, steamboats are also a feature of a number of the drawings in this sketchbook: see folios 2, 3, 18, and 22 recto (D35363, D35364, D35380, D35384; Turner Bequest CCCLVI 3, 4, 19, 23). This type of vessel was used frequently by Turner as a means of transport within Britain and the Continent. His drawings produced between 1833–5 for the Annual Tour print series (later gathered in one volume under the title The Rivers of France) often feature the sort of packets which he himself would have used to tour the Loire and Seine rivers (see, for example, Turner’s watercolour drawing Le Havre, Tour de François 1er of c.1832 (Tate D24699; Turner Bequest CCLIX 134) and the line engraving Havre, published in 1834 (Tate impression: T04698). The inclusion of the steamboat in the Ideas of Folkestone sketchbook, then, both registers Turner’s longstanding awareness of its signification with regard to modernity and maritime technological development and, on a compositional level, the aesthetic potential of the vessel. As Prints and Drawings Registrar Sarah E. Taft notes, steamboats appealed to Turner ‘for the way they looked’: he ‘used their bold blackness to produce striking effects in his landscapes’ and ‘took advantage of the way the black smoke from a steamer’s funnel made evident the currents in the air’.6 Turner noted in 1808 that pictorially reproducing the way steam vapour dispersed into the atmosphere was a means to evoke ‘wavy air, as some call the wind’.7 It is these and other atmospheric effects which Turner fundamentally sought to convey in his depictions of this Kent coastal town: the ‘Idea’ of Folkestone, the impression of its topographies and harbour landscapes.

The Ideas of Folkestone watercolours demonstrate the artist’s delight in the evocative possibilities of the medium. Dilute, modulated applications of pigment often allowed to bleed and feather upon the page coexist with vigorous dry-brush strokes producing a mottled gestural result. These formal effects amplify the atmospheric aspects of the view depicted in the drawing. This was a facet of Turner’s watercolours of interest to the artist David Hockney. In a dialogue with David Blayney Brown in conjunction with the Hockney on Watercolours exhibition, Hockney observes: ‘I don’t think that Turner was interested in the topographical landscape. He was not interested in using any mechanical devices ... to construct the landscape. So this meant he could look at the world in any kind of way. He was more interested in atmosphere – in a beautiful misty morning with its sunlight and shadows. Turner understood this process of looking’.8

Forms such as figures, boats, rivers, or buildings in Ideas of Folkestone are rendered in a summary often indistinct manner; reduced to their ‘absolute minimum’ according to Turner scholar Michael Bockemühl.9 That is to say, Turner does not seek to represent views of Folkestone mimetically, rather he attempted to convey the essence of the view before him. Bockemühl argues that it is this ‘open’ or indistinct quality of Turner’s late landscapes which in turn produces a ‘richness’ of aesthetic and ideational ‘experience’.10

Brown considers the Ideas of Folkestone drawings to some extent symbolic of Turner’s own emotional predicament in the mid-1840s. He finds in them ‘an old man’s vision, retrospective, selective, solitary, and not a little melancholy. Where Turner’s eyes had once been fixed mainly on the shore, and absorbed in its bustle and activity, he now looked out to sea, across wet and lonely sands, empty save for the odd horseman or beachcomber, into the infinity of the “loveliest skies in Europe”.’11

Regarding dating, Brown notes that no information is provided within the sketchbook to come to a definite conclusion as to when Turner was in Folkestone during 1845 or indeed if he was actually there at that time at all. The sketchbook may have been used ‘at different times during the year’ in Folkestone or in different locations.12 This date is traditionally attributed because Turner is known to have taken two excursions to the Kent coast in late spring – early summer and early autumn of that year.

For other sketchbooks with similarities in the style of handling to Ideas of Folkestone, see Turner’s Ambleteuse and Wimereux sketchbook, c.1845 (Tate; Turner Bequest CCCLVII); the Dieppe sketchbook of about the same date (Tate; Turner Bequest CCCLX); and the Channel sketchbook (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven). Turner scholar Andrew Wilton argues that this last sketchbook documents the artist’s journeys along the English and French Channel coast, basing his attribution of the date 1845 because of its parallels in handling to Ideas of Folkestone.13

For other of Turner’s sketchbooks in which Folkestone features as subject see the Richmond Hill; Hastings to Margate sketchbook of about 1816–19 (Tate D10475–D10477, D10479; Turner Bequest CXL 34a, 35, 35a, 36a); the Folkestone sketchbook of 1821 (Turner Bequest CXCVIII); the Holland sketchbook of 1825 (Tate D18855–D18864, D18866–D18879, D18883, D19399; Turner Bequest CCXIV 8–12a, 13a–20, 22a, CCXIV 282); the Holland, Meuse and Cologne sketchbook of about 1825 (Tate D19410; Turner Bequest CCXV 5a); the France and Folkestone sketchbook of 1826 (Tate D24107, D24109–D24135, D24138, D24167; Turner Bequest CCLVI 1, 2–14a, 15, 17v, 44a); the Folkestone (?) sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CCCLXII); and the Near Folkestone (?) sketchbook of c.1845 (Tate; Turner Bequest CCCLIV).

For Turner’s drawings and watercolours of the early 1820s in which Folkestone features as subject see Tate D17760, D17761 (Turner Bequest CCIII C, D) and Tate D18158, D25480 (Turner Bequest CCVIII Y, CCLXIII 357). In collections outside of Tate see also Folkestone, Kent, 1823 (Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati);14 Fishing Boats on Folkestone Beach, Kent, c.1828 (The National Gallery of Ireland);15 and Folkestone Harbour and Coast to Dover of c.1829 (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven).16 For Turner’s drawings and watercolours of the late 1820s and 1830s in which Folkestone features as subject see Tate D25185 and D25225, (Turner Bequest CCLXIII 63, 103). See also Turner’s oil painting Seascape: Folkestone (private collection).17

See ‘History of Folkestone Harbour and Cross Channel Links’, Folkestone Harbour Company, accessed on 30 January 2013, http://www.folkestoneharbour.com/pages/history.html .

Sarah E. Taft, ‘Steamboats’ in Evelyn Joll, Martin Butlin and Luke Herrmann (eds.), The Oxford Companion to J.M.W. Turner, Oxford 2001, p.309.

David Hockney quoted in Simon Grant (ed.) Hockney on Turner Watercolours, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2007, p.11.

Michael Bockemühl, J.M.W. Turner 1775–1851: Die Welt des Lichts und der Farbe, Cologne 1991, p.78; J.M.W. Turner 1775–1851: The World of Light and Colour, trans. Michael Claridge, Cologne 1993, p.78.

David Blayney Brown in Brown and Kenneth Reedie, Turner and Kent, exhibition catalogue, Royal Museum & Art Gallery, Canterbury 2001, p.15.

David Blayney Brown, Turner and the Channel: Themes and Variations c.1845, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1987, p.15.

Susan Morris, ‘A Turner Sketchbook at Sotheby’s’, Turner Society News, no.41, August 1986, p.4; see also Andrew Wilton, ‘A Rediscovered Turner Sketchbook’, Turner Studies, vol.6, no.2, Winter 1986, pp.9–24.

Technical notes

How to cite

Alice Rylance-Watson, ‘Ideas of Folkestone sketchbook 1845’, sketchbook, February 2013, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, June 2013, https://www