Turner Bequest CCXCI c 1–42

Sketchbook bound in boards, covered in red leather, with a brass clasp

42 leaves and pastedowns of white wove paper; page size 79 x 101 mm

Blind-stamped ‘CCXCI (c)’ front cover, top right

42 leaves and pastedowns of white wove paper; page size 79 x 101 mm

Blind-stamped ‘CCXCI (c)’ front cover, top right

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

References

This sketchbook remained undocumented before Finberg’s 1909 Turner Bequest Inventory, when he named it ‘Colour Studies (2)’ and associated it by implication with the Colour Studies (1) sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CCXCI b), dating them both to about 1834.1 Neither includes the usual Turner Bequest executors’ notes and endorsement or a schedule number from the 1854 inventory of Turner’s sketchbooks.2 Presumably they were put aside at the time on account of their sometimes erotic subject matter, which Finberg passed over in titling most pages with neutral variations on ‘colour sketch’ or ‘figure’ subjects.

Perhaps Finberg did not examine the contents closely, as he later guilelessly suggested that the pages ‘torn from a small sketchbook’ which appeared to contain ‘a memorandum in colour that [Turner] had made of the sky and sunset’ to serve as sails for a child’s model ship came from one of the Colour Studies books; this was as recalled in the words of the artist Robert C. Leslie (1826–1901; son of artist Charles Robert Leslie, 1794–1859), and supposedly occurred when he was staying at Petworth House in Sussex as a boy in 1834.3 Based on other primary sources, Ian Warrell has noted that the event was more likely to have happened in the autumn of 1836,4 though whether one of the Colour Studies books was involved remains a moot point, and the unrelated Oxford and Bruges sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CCLXXXVI) is another candidate.5 For more on Petworth, see the overall Introduction to the present grouping.

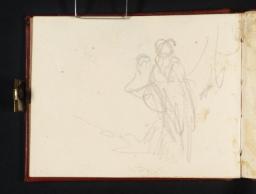

It was not until the 1960s when the two books, along with the Fishing at the Weir sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CCLXXXI), were addressed by Lawrence Gowing in terms of both the erotic character of their contents and their loose, improvisational technique.6 (Insofar as they address the two Colour Studies books in general, sometimes together with Fishing at the Weir, Gowing’s and others’ interpretations and comments as cited in this sketchbook’s literature are set out in the general Introduction to the three books.) Attempting to consider them as a coherent sequence, Raphael Rosenberg has suggested that the present book was filled first, followed by Colour Studies (1), and concluding with Fishing at the Weir, where the watercolours peter out after the first few pages.7

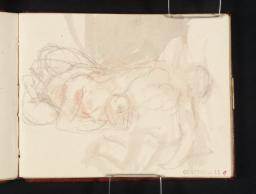

Andrew Wilton has proposed that the sequence between folios 1 recto and 12 verso (D28874–D28886) ‘form a series of studies narrating an erotic adventure’ as distinct from other ‘studies on similar themes throughout the book’.8 There may be a case for shortening this range slightly; Raphael Rosenberg has suggested that it ends at folio 11 recto (D28885),9 after the throes of passion. Folio 12 verso (D28886) is upside down in relation to the sketchbook’s foliation, and more probably belongs with a run of similarly inverted studies on the versos extending towards the back of the book in terms of its current numbering; these form a continuous sequence, albeit without a narrative, and were probably made working in from the ‘back’. In principle the ‘erotic adventure’ seems likely, as some of the scenes are more conventionally pictorial and carefully defined by drawing with the brush (albeit sometimes sexually explicit) than the often rather rough, undeveloped washes in the rest of the book. Jack Lindsay has imagined them as ‘the record of an episode at an inn (on the Rhine, perhaps). A set of delightful little paintings show a servant-girl undressing, a couple tumbling in the large bed, compositions derived from their embraces, and what are almost pure effects of colour and light derived from the experience.’10 Warrell has described the general ‘mood’ of the book as ‘lighter than its pair’, Colour Studies (1),11 although Gerald Wilkinson has called it the ‘less coherent’, with its ‘series of blots or smudges in pink and grey which here and there coalesce into sculptural figures’.12

The only inscriptions in this sketchbook are miscellaneous notes inside the front cover (D41220) and an apparent draft of poetry on folio 42 verso and inside the back cover (D28947, D41221). There is no specific internal evidence of when it was employed. Finberg’s date of about 1834 and others of a year or two later in subsequent sources have been taken into account, and the dates have been amended throughout to about 1834–6; this is also owing to certain aspects of the Fishing at the Weir and Colour Studies (1) books, which indicate that they too were in use between those dates.

Technical notes

How to cite

Matthew Imms, ‘Colour Studies (2) Sketchbook c.1834–6’, sketchbook, May 2014, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, September 2014, https://www