A History of Camden Town 1895–1914

David Hayes

In the early nineteenth century Camden Town had been a quiet, middle class suburb. But by the 1910s the district had become shabby and run down, with a different social mix. David Hayes reviews the early history of Camden Town and the life of its inhabitants in the early twentieth century.

The early suburb

The north London district first visited by Walter Sickert in 1888 to sketch at the Old Bedford music hall, and which in 1911 would lend its name to the Camden Town Group, was then a little over a century old. Until 1780 it had been only a wayside hamlet at the fork where the roads northward to Hampstead and Highgate diverged, known as the ‘village of Mother Red Cap’ after its best-known public house. ‘Ribbon development’ had begun along the main road (today’s High Street), the boundary between the estate of Lord Southampton to the west and, on the east side, that of Earl Camden, to whom the whole area owes it name. Started in greater earnest in 1791, the development of their fields on either side of the main road was gradual, and it was not until c.1850 that all the core parts of the new ‘town’ were fully built up.

Early Camden Town had been a quiet, middle-class, residential suburb. To encourage inhabitants of the ‘right class’, an imposing neoclassical chapel-of-ease, the Camden Chapel, was erected in Camden Street and consecrated in 1824.

By Sickert’s day, Camden Town had evolved into a crowded inner-London suburb with a very mixed character. The Regent’s Canal, whose banks would in due course be lined by warehouses and factories, was opened to traffic in 1820. In 1837 the London & Birmingham Railway cut through the fields to the west en route to Euston, separating the embryonic suburb, both physically and psychologically, from upper class Regent’s Park, to which it had originally aspired to belong. Opened in 1850 was a second railway, the North London, bestriding the district’s northern edge on a brick viaduct and bringing with it further smoke and noise.1

Housing

In the wake of the railways and canal came industry, and with industry a substantial working class population. This was further swelled in the 1860s by an influx from Somers Town (to the south) of large numbers of poor people displaced in the construction of the Midland Railway’s approaches to St Pancras. While the population had risen rapidly, the housing stock had remained essentially unchanged, and overcrowding was the inevitable result.

Most of Camden Town’s early houses had been designed for middle class families. These houses, in yellow stock brick, were typically of three storeys, with a basement service area and often an attic containing the servants’ quarters. Some smaller two-storey cottages had also been erected for the less affluent.2

By the end of the nineteenth century most of the housing stock was soot-stained and run-down. Multiple occupancy had become the norm: large houses originally built for the middle classes and their servants had been divided into apartments, and few premises were without boarders or lodgers. In 1905 the newly formed St Pancras Borough Council erected its first council flats, Goldington Buildings;3 and in the same year Lord Rowton opened Rowton House,4 offering basic accommodation for homeless men and vagrants.

Demographics c.1900

In 1898 the social reformer Charles Booth walked the streets of London, gathering evidence for a revision of his well-known, colour-coded ‘poverty map’. His notebooks portray Camden Town as a ‘middling’ sort of district, with no examples of either extreme poverty (which he coded black and which existed immediately to the south in the notorious slums of Somers Town), or of conspicuous wealth (shaded yellow and evident to the west in the grand Nash terraces encircling Regent’s Park).5

Although Booth’s notes about Camden Town are peppered with expressions such as ‘going downhill’, a surprising number of streets are still coded red (for ‘middle-class, well-to-do’). These include the High Street and its offshoot Park Street (now Parkway), whose shopkeepers were widely regarded as the most well-off inhabitants. Likewise shown as ‘middle-class’ are the area’s westerly streets near to Regent’s Park, such as Gloucester Crescent, where Sickert lived at number 68 in 1912. Just around the corner, at 11 Oval Road, was the childhood home and probable birthplace in 1869 of Walter Bayes, who, unlike other Camden Town Group members, could thus claim a lifelong connection with the district.6

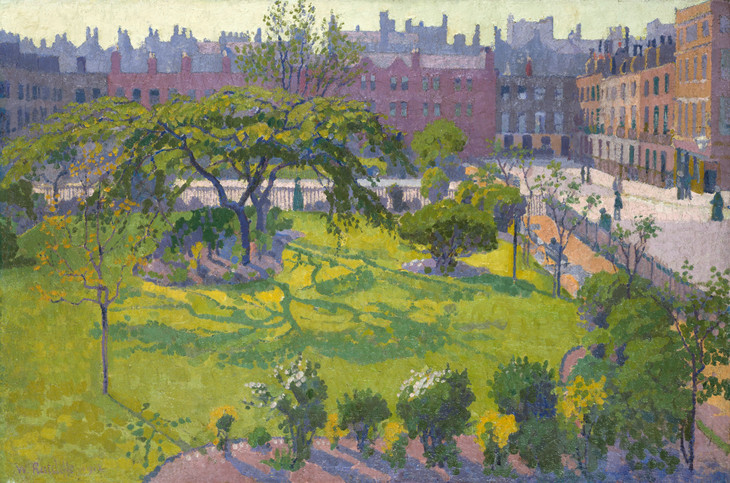

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Houghton Place 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 515 x 614 mm

Tate N03839

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1927

Fig.1

Spencer Gore

Houghton Place 1912

Tate N03839

Opposite Harrington Square lay Mornington Crescent (fig.2), then ‘largely let in apartments’. Number 31, in 1901, was the family home of an Anglican clergyman, but with a publisher’s assistant as lodger.9 It was probably the latter’s room that Gore took over in 1909, painting from his window the private garden enclosure, equipped with tennis courts for key-holding residents, which then still fronted the Crescent (fig.3).10 At its south end, and backing onto what was by then the London & North Western Railway (LNWR), was number 6, converted into a lodging-house and home to Sickert in 1905 on his return from France.11

Mornington Crescent, northwest quadrant, including No.31 where Spencer Gore rented a room in 1909–12 c.1904

Postcard

90 x 140 mm

Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Photo © Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Fig.2

Mornington Crescent, northwest quadrant, including No.31 where Spencer Gore rented a room in 1909–12 c.1904

Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Photo © Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Mornington Crescent 1911

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 616 mm

British Council

Photo © Rodney Todd-White & Son

Fig.3

Spencer Gore

Mornington Crescent 1911

British Council

Photo © Rodney Todd-White & Son

Close by was 247 Hampstead Road, which housed Sickert’s studio and art school in 1908. Beyond the railway bridge, in the same road, were the sites of his earlier etching schools at number 209 and No.140 (which the artist dubbed Rowlandson House; Tate N05088, fig.4). Booth described Hampstead Road as being ‘in a shocking state of repair’ and undergoing ‘great social deterioration’. Westward lay Harrington Street (fig.5), described by Booth as a ‘lodging street’ and the site of Sickert’s rented house at number 60 in 1907; and ‘inferior’ Granby Street, where Gore lived at number 15;12 the latter street’s north side had been swept away in the widening of the railway cutting in 1900–6.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Rowlandson House - Sunset 1910–11

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 502 mm

Tate N05088

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

© Tate

Fig.4

Walter Richard Sickert

Rowlandson House - Sunset 1910–11

Tate N05088

© Tate

Harrington Street, home to Walter Sickert in 1907 c.1904

Postcard

90 x 140 mm

Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Photo © Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Fig.5

Harrington Street, home to Walter Sickert in 1907 c.1904

Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Photo © Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Also west of Hampstead Road – and, strictly, not part of Camden Town – lay a district of largely working class housing originally conceived by John Nash as a ‘service area’ for his Regent’s Park development. Here lay Munster Square and Clarence Gardens (Tate T03359, fig.6), which would each be portrayed by various Camden Town Group members. A third square, Cumberland Market, had been laid out in 1819 for the sale of hay; though never a great commercial success, it functioned until closed in 1926. The houses lining the Market included number 49, the studio of Robert Bevan, where each Sunday in 1914 the members of the Cumberland Market Group exhibited their work.13 In nearby Augustus Street, number 31 had in 1905 functioned as one of Sickert’s etching schools. This area was shaded by Booth in a mixture of pink (‘fairly comfortable, good ordinary earnings’) and purple (‘mixed: some comfortable, others poor’).

So, too, were large parts of Camden Town proper, but here there were several pockets of real poverty, coded blue: off the High Street, for example, in Stanmore Place, a row of ten especially mean houses with small yards to the front but no space at the rear; Carlow Street and Nelson Street (now Beatty Street), barely a hundred metres from Mornington Crescent, where one small house contained twenty-one inhabitants; and Union Terrace, a particularly squalid street north of the Camden Town Underground station site.

Prostitution

In Union Terrace Booth noted a brothel, ‘now closed’; but prostitution was not confined to the poorer streets; it also existed in the generally ‘middle-class’ Camden New Town, the outlying, more spacious neighbourhood to the north-east, completed only in 1871 and focused on leafy Camden Square. On the edge of this area, at 29 St Paul’s Road (now Agar Grove),14 lived the prostitute Emily Dimmock, victim of the so-called ‘Camden Town Murder’ of 1907, which inspired Sickert’s series of ‘murder’ paintings. The lurid press coverage of the subsequent trial and acquittal of Robert Wood reinforced, and possibly exaggerated, the general perception of Camden Town as a hotbed of sleaze and vice.15

Industry and art

The railways were major employers of local labour; the vast goods yard of the LNWR dominated the north-western part of Camden Town, and three mainline termini were nearby. The district’s staple industry, however, was piano manufacture, having been drawn north from Fitzrovia by the ease of transporting timber by canal. It was often said that every street in north London contained a piano works, and in many parts of Camden Town this was literally true; Bayham Place was a notable piano-making enclave. Other major, well-established enterprises included Gilbey’s, the wine merchants and gin distillers, whose numerous premises covered twenty acres on either side of the canal, and Goodall’s in Great College Street, the world’s largest manufacturers of playing cards.

New factories were still opening: Idris, the soft-drink makers, set up in Pratt Street in the 1890s; Oetzmann’s opened a cabinet factory in the High Street itself, beside the uninspired statue of Sickert’s father-in-law by his first marriage, Richard Cobden; and in 1904 the huge bakery of the Aerated Bread Company was erected in Camden Road.

Closed in 1905 was the Bayham Street works of Dalziel Brothers, whose long-standing engraving business had provided work for many local artists and printmakers. Camden Town had attracted artists from the outset, offering inexpensive accommodation within easy reach of central London. An early resident was George Morland who from 1787 spent three years in the fledgling suburb at the height of his success.16 The North London School of Drawing & Modelling flourished from 1850 in Mary Terrace, and artists’ studios were later established, including, in 1865–9, the purpose-built Camden Studios in Camden Street.

Shopping

Serving the shopping needs of the heterogeneous population was the busy High Street, graced at its south end by the statue of Cobden (fig.7).17 Single-storey shops had been built over the front gardens of the original houses, some to be replaced later by purpose-built premises. Lining the typical Victorian shopping street were dozens of retail outlets to satisfy everyday needs, including food and clothing shops of every kind, and no shortage of fried fish shops of the kind depicted by Stanislawa de Karlowska (Tate N06238, fig.8); of these there were no fewer than five either in, or just off, the High Street’s southern end.18

Camden High Street, south end, looking north past the Cobden statue c.1904

Postcard

90 x 140 mm

Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Photo © Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Fig.7

Camden High Street, south end, looking north past the Cobden statue c.1904

Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Photo © Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Stanislawa De Karlowska 1876–1952

Fried Fish Shop c.1907

Oil paint on canvas

support: 337 x 394 mm; frame: 440 x 496 x 72 mm

Tate N06238

Presented by the artist's family 1954

© Tate

Fig.8

Stanislawa De Karlowska

Fried Fish Shop c.1907

Tate N06238

© Tate

Catering for the middle classes were more specialised shops, stationers and booksellers, for example, and sellers of bicycles and sewing machines. 1895 saw the opening of the area’s first large store, the furnishing emporium of Bowman’s, while for those of more modest means a street market opened in Wellington Street (now Inverness Street) in 1901. Opened in 1911 was the area’s first chain store, the Penny Bazaar, taken over two years later by Marks & Spencer.

Leisure

Drinking was a popular pastime in Camden Town, which boasted a plethora of public houses: over a dozen lined the High Street and there was scarcely a back street without one or more. Their profusion was popularly attributed to the dry and dusty conditions in which thirsty piano-makers worked. Some pubs provided music-hall entertainment. Of these the most prominent was the Old Bedford, which had evolved from the old Bedford Arms public house and which was superseded, in turn, by the baroque-fronted New Bedford Palace of Varieties opened in 1899; both incarnations were depicted at various times by Sickert (Tate N06174, fig.9) and Gore also painted the New Bedford (Tate T02260, fig.10).19

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The New Bedford c.1914–15

Oil paint on canvas

support: 914 x 356 mm; frame: 1105 x 545 x 62 mm

Tate N06174

Bequeathed by Sir Edward Marsh through the Contemporary Art Society 1953

© Tate

Fig.9

Walter Richard Sickert

The New Bedford c.1914–15

Tate N06174

© Tate

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

A Singer at the Bedford Music Hall 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 533 x 432 mm

Tate T02260

Presented by Mr and Mrs Robert Lewin through the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1978

Fig.10

Spencer Gore

A Singer at the Bedford Music Hall 1912

Tate T02260

Staging plays and hosting public meetings was the Royal Park Hall in Park Street, successor to the Park Theatre which had burned down in 1881.20 Also opened in 1900 at the south end of the High Street was the imposing Royal Camden Theatre,21 which by 1909 had become a variety theatre, the Camden Hippodrome, and by 1913 a cinema. In Delancey Street, a former public hall turned ‘billiards lounge’ became a roller-skating rink in 1903, capitalising on the popular craze of the day, and then in 1908 the Fan cinema. Further picture houses opened soon after.22

Highly popular were the St Pancras Baths & Washhouse in King Street, which offered two swimming pools, besides meeting the laundry needs of the many locals with inadequate washing facilities at home. Although for outdoor activities there was virtually no open space in Camden Town itself, the inhabitants at least had Regent’s Park (with its Zoo) on their doorstep.

‘Improving’ institutions

To serve the burgeoning population, six new Anglican parishes had been created, including St Matthew’s (1854), whose church spire graces the skyline in Gore’s Mornington Crescent 1911 (see fig.3). Catering for nonconformists were Congregational and Presbyterian chapels, and the New Camden (Methodist) Chapel which in 1889 superseded an earlier Wesleyan place of worship. Several mission halls targeted the poor.23

The Camden Hall in King Street housed a Working Men’s Club & Institute, and a Free Library from 1877. In the wake of the 1870 Education Act, three Board schools opened in Camden Street, the last in 1895. Nearby were the new premises of the Working Men’s College, removed to Crowndale Road from Bloomsbury in 1906.

Transport

Camden High Street, showing the recently electrified tramway c.1910

Postcard

Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Photo © Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Fig.11

Camden High Street, showing the recently electrified tramway c.1910

Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Photo © Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Conclusion

The Camden Town known to Sickert and Gore could indeed claim to exemplify the simple life of the middle and lower classes that was depicted in the paintings of the Camden Town Group. Its commercial heart was being modernised, and from the formation of St Pancras Metropolitan Borough in 1900 there emerged a new civic pride. But two World Wars and an intervening Depression would lead only to further deterioration of the housing stock and desertion of the area by the middle classes. Only in the last decades of the twentieth century would they return to the newly part-‘gentrified’ district, and would Camden Town again become so socially diverse. Today, in Mornington Crescent, described by Wendy Baron as recently as 1979 as ‘particularly decrepit’,24 a two-bedroom flat can fetch not far short of half a million pounds.

Acknowledgements

Most historical details not otherwise attributed have been drawn from the Camden History Society publication, Streets of Camden Town (London 2003). The contribution of fellow members of the Society’s street research team, led by Steven Denford, is gratefully acknowledged.

Notes

Such as that in Bayham Street occupied in 1822–3 by the debt-ridden family of the young Charles Dickens.

Now Goldington Court; Ethel Le Neve, secretary and the mistress of Dr Crippen, was an early resident.

Home in 1901 to a furniture salesman and his family, and a widowed hairdresser (Census 1901, RG13/145); and coincidentally the house where Charles Dickens had earlier installed his mistress Ellen Ternan.

Maureen Lee Connett, ‘Spencer Gore, the Story of a Painter’, Camden History Review, vol.15, 1985, p.19. The gardens were covered in 1926–8 by the ‘Black Cat’ cigarette factory of Carreras.

No.6 bears a blue plaque to Walter Sickert. In 1901 it was a lodging-house run by Mrs Louisa Jones, her lodgers being a medical student, a tailor and a ‘company secretary’. Lodgers at adjacent properties included students at the Royal Veterinary College in Great (now Royal) College Street. Several neighbours were German or Swiss. A few doors away at 263 Hampstead Road was the former home of the caricaturist George Cruikshank (also blue-plaqued).

Occupied in 1901 by a postman, his wife and four children; an omnibus driver and his family; and a widow with her son, a clerk.

Marian Kamlish, George Morland, a London Artist in Eighteenth-Century Camden, Camden History Society, London 2008, pp.32–93.

Marian Kamlish, ‘The Alhambra of Camden Town, the Rise and Fall of Sickert’s Dear Old Bedford’, Camden History Review, vol.19, 1995, p.30.

David Hayes is a member of the Camden History Society and edits the annual Camden History Review.

How to cite

David Hayes, ‘A History of Camden Town 1895–1914’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www