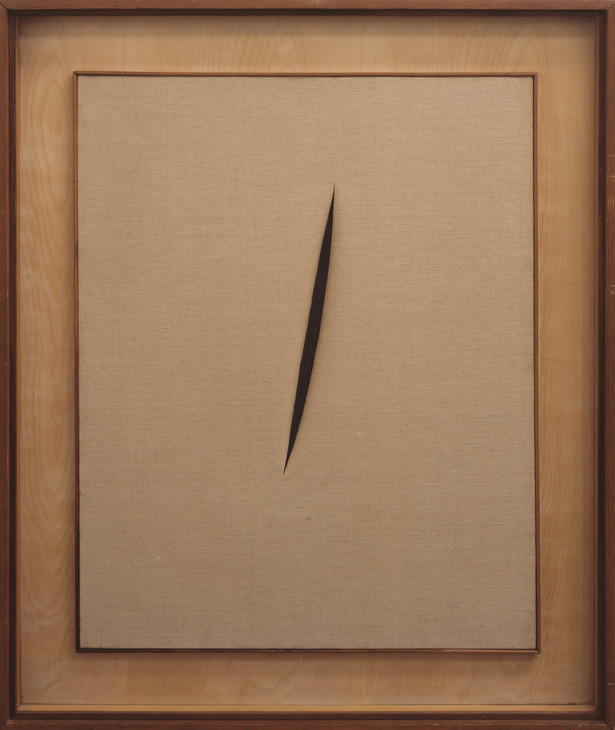

Sublime Sexuality: Lucio Fontana’s Spatial Concept ‘Waiting’

Philip Shaw

Lucio Fontana 1899–1968

Spatial Concept 'Waiting' 1960

Canvas

unconfirmed: 930 x 730 mm; frame: 1161 x 982 x 86 mm

Tate T00694

Purchased 1964

© Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milan

Fig.1

Lucio Fontana

Spatial Concept 'Waiting' 1960

Tate T00694

© Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milan

Lucio Fontana began to punch holes (or buchi) through his canvases in 1949–50, the aim being literally to break through the surface of the work so that the viewer could perceive the space that lies beyond. Fontana seems to have regarded this gesture as a means of disclosing the unlimited space of the sublime, announcing, ‘I have created an infinite dimension’.1 Towards the end of the 1950s, the artist experimented further with cuts (or tagli) executed with a razor. Although carefully premeditated, the slashes in these later canvases – Spatial Concept ‘Waiting’ (Tate T00694, fig.1) dates from 1960 – appear spontaneous and bear a certain resemblance to the ‘zips’ in the abstract expressionist paintings of Barnett Newman. The effect of Fontana’s cutting varies from canvas to canvas. In some works, such as this one, the viewer is drawn into the space beyond the canvas; in other works the slash seems to erupt outwards, conveying the force of the original assault towards the viewer in a way that is both energetic and terrifying. Despite the obviously violent implications of his art, Fontana maintained that he had set out to construct rather than to destroy.

The sense in which such work holds creative and destructive elements in tension has a clear connection with the comingling of pain and pleasure that are distinctive features of the sublime. Where Fontana goes further, however, is in his unstinting focus on the unconscious links between sublimity, terror and sexuality. To understand how these links emerge in this work it is helpful to consider an example from the world of advertising. In Britain in the 1980s Charles Saatchi spearheaded the design of a poster for the cigarette brand Silk Cut that depicts a swath of purple silk with a single slash in the fabric. Through the creation of a carefully orchestrated set of associations, linking luxury (the opulent fabric), violence (the razor cut) and female sexuality (the obscure object of desire which the cut resembles), the poster effectively circumvented restrictions on the use of explicit sexual imagery in advertising. In Freudian terms the Saatchi campaign artfully manoeuvred between the twin poles of idealisation and sublimation in the ego’s relationship with the sexual impulse.

In the realm of fine art, Fontana’s work seems no less concerned with the sexualised foundation of the viewing experience. In the terms of Thomas Weiskel’s groundbreaking reading of The Romantic Sublime (1976), Spatial Concept ‘Waiting’ seems to dramatise the moment when the illusory integrity of the ego succumbs to the overwhelming might of the dynamic sublime.2 Unable to resurrect the pleasure principle that would enable the ego to circulate around such terrifying ‘delight’, the unwitting viewer of Fontana’s work is brought to the terminus of their desire.

Philip Shaw is Professor of Romantic Studies in the School of English at the University of Leicester and Co-Investigator of ‘The Sublime Object: Nature, Art and Language’.

How to cite

Philip Shaw, ‘Sublime Sexuality: Lucio Fontana’s Spatial Concept ‘Waiting’’, in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication, January 2013, https://www