Contemporary Art and the Sublime

Julian Bell

More than six decades after the publication of Barnet Newman’s 1948 article ‘The Sublime is Now’, artists are still trying to give the sublime a contemporary treatment. The sheer range of their attempts makes it harder than ever to offer a narrow definition. The artist and writer Julian Bell offers here his own critical reflections on the contemporary sublime, surveying recent art and considering his own practice.

The sublime is a term that has been heavily employed in art writing over the past twenty years. Too heavily, it may be. References to it have come from so many angles that it is in danger of losing any coherent meaning. We have been offered everything from ‘the techno-sublime’1 and ‘the eco-sublime’2 to ‘the Gothic sublime’3 and ‘the suburban sublime’4: anything from volcanoes and vitrines to still lifes and soft toys may be sniffed at for sublimity.5 How did we arrive at this state of affairs?

From our current perspective, we can track the term’s usage winding stream-wise across the landscape of cultural history. On the far mountainsides there is the glint of the Pseudo-Longinus, circa first-century treatise, our earliest reference point. Then we catch sight of two well-known waterfalls, Edmund Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry of 1757 and Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment of 1790. It is easy to trace the swelling river of references to the sublime that rolls on down from these two, but as the constructions of modernism rise up in the later nineteenth century, the river’s course gets increasingly obscured. Suddenly in 1948 it swings into view again, traversed by the bridge of Barnett Newman’s rhetoric. But here in the foreground, as of the 2010s, we seem to stand amidst a delta. Channels of discourse about the sublime meander all around us, but which is the main flow, which the subsidiary, which the navigation canal or ditch for irrigation has become almost impossible to tell. Ideally, I should like to draw a map of this muddle; pragmatically, I hope at least to offer a ground-level topographical sketch.

In the first section of this essay, I shall offer a directly personal take on the theme that will open out on to various aspects of current art-world thinking and practice. Many of the tactics and visual effects discussed here can easily be related to the tradition of artistic production stimulated by the writings of Burke. In the second section, I shall consider some reinterpretations of the theme that are distinctive to the recent past, even if in principle some are linked to the philosophy of Kant. The period under discussion – the phase of art history currently designated ‘contemporary’ – effectively begins during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Finally, I shall offer some brief qualifications, suggesting what the sublime is not. The sublime has always implied the over-powering, but once it becomes the all-swallowing, the term eats up its own meaning.

The sublime as it gets made

A painting by the author

I approach the sublime not as a philosopher or cultural theorist, but as an artist. Specifically, as the painter of a canvas to which many viewers have responded with mentions of ‘the sublime’. They do so, I should add, to describe the tradition to which they feel the painting relates, rather than to praise it. I shall try to discuss this canvas quite simply as a symptom of the mentality of a British painter who was born in 1952, asking how far that symptom might assist in a broader diagnosis of artistic trends.

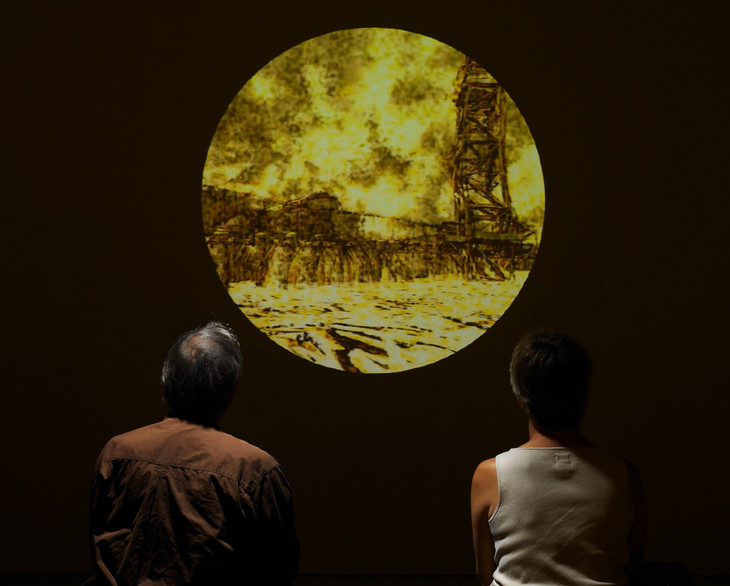

The painting in question is named Darvaza 2010 (fig.1), after a site in Turkmenistan that I visited as a tourist. The site, in the middle of the Karakum Desert, was drilled by Soviet engineers reconnoitring for fuel in 1971. Hitting a cavity, the engineers decided to burn off the gas inside, but the resulting inferno passed quite beyond their control. They abandoned the site, which was far from human habitation. At the time I visited, the vast crater was still burning away, night and day, among the bare compacted sands of the Karakum.

Julian Bell

Darvaza 2010

Oil paint on canvas

1397 x 2438 mm

© Julian Bell

Fig.1

Julian Bell

Darvaza 2010

© Julian Bell

On my return home, I represented what I had seen on a canvas eight-foot wide. On the crater’s far side, I placed a small male figure, just over an inch high, standing turned towards it, his palms raised to face the upward surge of heat. The figure functions as an indicator of scale and equally obviously as a testimonial. This is I, it tells the viewer, I the artist: I witnessed what I am showing you. I was a tourist who came close to this spectacle and now I wish to draw you close to it likewise. With that objective in mind, I took two chief decisions in translating the sketches and photos I had made at the original site into a picture intended for a British gallery wall. I chose to crop what could be seen of the crater’s round rim, so that there is no central foreground and from the picture’s base all is fire. And so as to set that fire ablaze, I took the white-primed canvas – this was my first act in marking it – leant it at an angle, and poured down, from what would become its base, a loose turpentine solution of a very strong yellow, letting the liquid stain and sediment however it chanced to run.

The results required editing with a brush in order to arrive at a shaped space, a crater that would seem to cup and enclose any viewer who drew near the canvas’s eight-foot span. But this way, inviting a relatively random process into the making of the image, I could feel that I was reaching out to touch something other in my studio – something not entirely self-willed and human – even as I had confronted something powerfully other, standing a previous evening by that flame lit cliff-edge.

A tradition of the pictorial sublime

What I was doing conformed, as the critic Jonathan Jones has noted,6 to a pattern of artistic behaviour that is over two centuries old. Joseph Wright of Derby, returning from a visit to Vesuvius in 1774 to create a number of images for British viewers, upended his brush, forsaking its bristles for its butt, or took to a palette knife in order to conjure up the primal force of the geological phenomenon he had observed (Tate T05846, fig.2). These randomising tactics are still more in evidence in the purely imaginary spectaculars created by John Martin in the 1840s: the topographies of his The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah 1852 (Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne) and his Plains of Heaven 1851–3 (Tate T01928, fig.3) coalesce around swooshing force-fields of oil paint, here accreted, there vaporously fine. A more recent interplay between free-flowing washes and controlled image design can be found in the awestruck landscapes Michael Andrews created in the mid-1980s, following a pilgrimage to Australia’s Ayers Rock (Tate T06677).

Joseph Wright of Derby 1734–1797

Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples c.1776–80

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1220 x 1764 mm; frame: 1461 x 1941 x 95 mm

Tate T05846

Purchased with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund, Friends of the Tate Gallery, and Mr John Ritblat 1990

Fig.2

Joseph Wright of Derby

Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples c.1776–80

Tate T05846

John Martin 1789–1854

The Plains of Heaven 1851–3

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1988 x 3067 mm; frame: 2415 x 3485 x 175 mm

Tate T01928

Bequeathed by Charlotte Frank in memory of her husband Robert Frank 1974

Fig.3

John Martin

The Plains of Heaven 1851–3

Tate T01928

Wright of Derby, an acute barometer of intellectual trends, undoubtedly painted with an awareness of Burke’s 1757 Enquiry. He takes up a challenge that Burke doubted painters could meet: for the young Irishman argued that ‘painting, when we have allowed for the pleasure of imitation, can only affect simply by the images it presents’7; whereas the words used in poetry can affect us ‘much more strongly’8 than the things they represent. Poetry, therefore, with its suggestive obscurity, was the art that could bring us closest to the sublime – ‘the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling’;9 a state of ‘astonishment’ including a ‘degree of horror’ that ‘anticipates our reasonings, and hurries us on by an irresistible force’.10 Burke contended that ‘darkness’ – the darkness of words dying away into silence – ‘is more productive of sublime ideas than light’, the condition within which paintings present their static imagery. And yet he allowed that ‘such a light as that of the sun, immediately exerted on the eye, as it overpowers the sense, is a very great idea’.11

Wright of Derby chose to exploit that possibility. Dazzling light is the type of overpowering optical impact his views of Vesuvius seek to ‘exert’ – an impulse also followed by John Martin and indeed myself. And the chance-courting studio tactics in each case are related, at least by natural sympathy, to the temporal rhetoric Burke employs: ‘immediately’, ‘hurries us on’ – when Burke is talking about the sublime, he often sounds like a drug user seeking a ‘rush’. Except of course that his thrill-seeking falls within respectable channels – the appreciation of nature and of art. Burke’s innovations in aesthetics challenged visual artists to disrupt the stasis of the two-dimensional image and, by the same token, the beautiful, which he interpreted as the perfectly self-contained. But did such tasks lie within their capacity? Their efforts, after all, generally lie contained within gallery walls: viewers always have the option to leave by the door. This image, the viewer may say, has no hold over me.

Going back to the eighteenth-century formation of an ‘art of the sublime’, I have been searching for a provisional working grip on this paradoxical concept. Let us take it for a controlled encounter with power that is beyond our control.

The scale of the sublime

A space modelled into the likeness of a crater – literally, a bowl-shape – that is nearly eight feet wide: such a space will invite the viewer to step in close, and then do its best to engulf him in a fiery embrace. Once you approach the canvas of my Darvaza, your eyes are going to need to look far to the left or right to find any rim to clutch at, let alone a stable foothold. So ran my working idea. And then, affecting it from an early stage, there was an awareness that I was due to exhibit in a largish public gallery. I needed a painting that would make a firm, strong impact on anyone who entered the room, before they turned to other works of mine with other agendas. Showmanship, in other words, gets inextricably bound up with an artist’s desire to deliver the sublime. This is hardly novel – think of the legendary attention-seeking of J.M.W. Turner, not only blasting his Royal Academy competitors into insignificance with the final varnishing-day touches to his marine spectaculars but giving them titles that insisted (probably falsely) on their own eye-witness status.

Richard Serra

The Matter of Time 2005

Installation of seven sculptures, weatherproof steel, Varying dimensions.

© 2012 Richard Serra/DACS

Fig.4

Richard Serra

The Matter of Time 2005

© 2012 Richard Serra/DACS

And yet this permanent exhibit inside the Guggenheim could be seen in terms of retreat. Produced between 1994 and 1997, it followed a much publicised legal contest which Serra fought and lost, his struggle to keep Tilted Arc, a 120-foot curved wall of steel originally erected in 1979, in place in a New York square. Serra’s sculpture presented a neighbourhood public with an obstruction that not only was daunting and resistant to interpretation but which they could not avoid as they walked the street: in effect, an uncontrollable uncontrolled. Their rejection of a challenging, ‘advanced’ sculpture has had repercussions.15 The past twenty years have seen a plethora of outsize outdoor sculptures (Jeff Koons and Anthony Gormley are familiar field-leaders), but by one means or another these works mostly seek to ingratiate, modulating the sublimity their scale proposes.

Instead, turn-of-the-millennium culture has kennelled the sublime. The Frank Gehry-built museum in Bilbao – another sort of materialistic masterpiece, as shimmering and heady as the steel maze that it houses is dun and obdurate – is one such monster-cage. Dia:Beacon in upstate New York is another, a resource of vast orthogonal interiors that bracingly complement the most ambitious artworks of the minimalist movement, the stable out of which Serra emerged. And Dia:Beacon’s aestheticised reinterpretation of an architectural space designed for early-twentieth-century industry is of course matched by Tate Modern with its Turbine Hall.

Anish Kapoor

Marsyas 2002

Installation at Tate Modern

© Tate Photography

Fig.5

Anish Kapoor

Marsyas 2002

© Tate Photography

The content of the sublime: global

Fear of what? What is that ‘something which one immediately has to recognise is bigger’? Does the contemporary art of the sublime have some substantive content in mind? Or do its meanings reside in its very nihilism, its hankerings after the sheer effect of power? Or is that taking matters too seriously? Why should we not simply celebrate showmanship, in this our age of spectacle?

Returning to my own studio, I would like to review various potentially significant concerns that passed through my mind as I worked on my Darvaza. Some of these thoughts were about the planet. As we stood by that crater edge in the Karakum, we could see old pipelines dangling and breaking away into the abyss. Central Asia is in fact littered with jagged relics of Soviet industrialisation in all its furious, heedless hubris. On a separate stretch of barren sands, we got shown a rusting fleet of trawlers: the inland Aral Sea they had once fished had evaporated after the waters to feed it were rerouted to boost cotton production yields in another state of the USSR. But anyone with the faintest interest in what goes on around them will know that the march of ruination goes far beyond that little lamented twentieth-century political experiment. The frontline has simply moved on: we might locate it now in the dammed Yangzi valley, or in the uprooted forests of the Amazon or of Kalimantan.

Edward Burtynsky

Oil Spill #2, Discoverer Enterprise, Gulf of Mexico, May 11, 2010

Digital, colour print on paper

1524 x 2032 mm

Photo © Edward Burtynsky courtesy: Nicholas Metivier, Toronto / Flowers, London

Fig.6

Edward Burtynsky

Oil Spill #2, Discoverer Enterprise, Gulf of Mexico, May 11, 2010

Photo © Edward Burtynsky courtesy: Nicholas Metivier, Toronto / Flowers, London

Beauty, here, seems to coexist comfortably with sublimity because the image has the status of reportage. Photography outside the studio, being tethered to external, real-world processes, has a weighting unlike other art forms: it can persuade us that it is those processes which beautify, rather than individual human volition. Since painting has no such grip on factuality, I saw little point in including those broken pipelines in my picture. (They would merely have complicated the design.) But if painting cannot stand up in court as evidence of what is going on physically on this planet, perhaps it could still tell us something imaginatively about the nature of massed human volition? For you might argue that the uncontrolled forces welling up to pollute the Gulf of Mexico are at root consumer avidity and the pursuit of profit. Concluding a spirited attempt to identify a genuine sublime for our times, the American art critic Thomas McEvilley declared that ‘the unknown face of global capitalism is terrifying in its vastness. Art and technology and so on are just role-players in the grand game.’17 Here, he argued, was an object truly worthy of our fear.

‘Capitalism’ is a master-abstraction of massed human processes, never wholly clear to the view – and yet, just as Burke argued when it came to poetry, that obscurity can add to its imaginative significance. Think of the alarm that a ‘free-falling’ diagonal on an economics graph can induce. This is the level of abstracted signification worked by the graphic language of the New York-based artist Julie Mehretu. Her melodramas of swooping vectors and nested graphemes, with their bravura, baroque complexity, seem to picture the dynamics of the age on a very large and general scale. Sometimes a local detail snags the quasi-infrastructural flowchart into specificity: in Dispersion 2002 (fig.7), a ghost aeroplane provides it. The reference, easy to intuit, is to events in New York the previous September. Here is visual art attempting zealously to respond to a moment of global crisis and convulsion. Mehretu’s work seems to ask for the description ‘tremendous’ – an epithet that closely tracks ‘sublime’, touching on both Burke’s ‘horror’ and his ‘astonishment’.

The content of the sublime: cosmological

The sublime may be political in effect – if it ‘hurries on’ our reasonings, prompting us to this or that response – and yet it cuts across morality: it ‘anticipates’ those reasonings, oblivious of good or evil. The spectacle of 9/11 could at once constitute an imagistic master-stroke (hailed as such by Damien Hirst and Anselm Kiefer, and anxiously so acknowledged by various cultural theorists) while at the same time remaining humanly contemptible. Its sublimity by another light reappears as banality: the mindset involved is one many male adolescents pass through and a few never leave. Most innocently computer-game their way through this psychic terrain. On the other side of that zone, some come out with artworks which give contained poetic shape to schemes of world-destruction and world-reconstruction.

Titanic structures tower overhead or tumble into an ocean traversed by some bobbing boat from which we look out, in a digital animation by the British-born, USA-based Matthew Ritchie. The Iron City 2002 (fig.8) belongs within a larger sequence in which, according to the artist,

First the universe assembles itself into a garden, and it’s sort of like the beginning of the world. [But here] gradually that world decays and falls apart and is turned into a kind of ruined city, which is the world we’ve created. And then that ruined city transforms gradually into The Morning Line [the work’s overall title], which then dissolves back to the beginning of time and the whole thing becomes a kind of endless narrative loop.’18

On one level Ritchie’s project has a direct contemporary agenda, speaking to the often apocalyptic pessimism with which people conceive the twenty-first century: ‘The idea is to confront and perhaps even transcend the rhetoric of fear that has recently come to dominate all discussions of the future.’19 But as in several installation projects he devised during the 2000s, the immediate means to hand point his viewers towards a large scale reflection on change and possibility in general, informed by readings of physics and cybernetic theory.

Anselm Kiefer born 1945

Lilith 1987–9

Oil, ash and copper wire on canvas

support: 3815 x 5612 x 500 mm; support, each: 3815 x 2806 x 50 mm

Tate T05742

Purchased 1990

© Anselm Kiefer

Fig.9

Anselm Kiefer

Lilith 1987–9

Tate T05742

© Anselm Kiefer

Andreas Gursky

Shanghai 2000

C-print

2800 x 2000 x 62 mm

© Andreas Gursky/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/DACS 2012Courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin London

Fig.10

Andreas Gursky

Shanghai 2000

© Andreas Gursky/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/DACS 2012Courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin London

If we are seeking an adequate object and content for our subjective sensations of sublimity, then the universe by definition provides an answer, the universe being absolutely big. But if we are to produce artistic representations, then we must seek some way to grapple with that totality, and this is where a scheme of interrelated cosmic states becomes relevant. Kiefer’s mythologies mull over such schemes continually, often by way of alchemy; Ritchie, using time-based media or interactive game scenarios, represents states as they develop and succeed one another.

For my own part, painting Darvaza, the idea of a succession of states implicitly governed the progression of the work – from a white-primed canvas to a liquid yellow staining to the many deeper hues that my brushes eventually laid down. Running backwards through that sequence, you move away from solidity, this peculiar local condition in which a few objects in the orbits of stars happen to find themselves. You move back through gaseous flame towards plasma – towards the condition in which particles dance about in such a white heat that they become electrically conductive. For plasma is the state in which, overall, most matter exists: the condition of the sun from which, historically, the materials of our planet originated; this universe’s vast and humanly intolerable normality.

The content of the sublime: theological

But another theme, far more immediate than the counter-intuitive, science-derived reflection mentioned above, was much on my mind as I painted Darvaza.

The title of my painting means ‘gateway’ in Persian. The name was in fact originally given to a camel halt in the Karakum Desert, but since 1971, when the Soviet gas probe blew up, locals have understandably taken it to mean ‘gate of hell’. Hell as a pit of fire is an image that is vivid and potent to any reader of the Qur’an and which remains verbally alive wherever cultures have been formed around the Bible. In those scriptures, the pit of fire is the ultimate threat to those who disobey God. It is how God appears to us at his most terrible. And yet an interesting thing happens if you start depicting a pit of fire. You are obliged to visualise light, and light, in the same scriptures, is a facet of God that draws us towards him. The red and yellow tints of your flames fade back to the same white ground that supplies your painting with the radiance of the sky – of heaven, in other words.

Symbolically, this is in accordance with standard theology. Humans are bound to approach God in his unity from multiple, circumstance-bound perspectives and these facets in which he shows himself will at first appear to contrast, but on deeper inspection will start to dissolve. God’s fearfulness – his sublimity – is for the Abrahamic religions ultimately subsumed within his radiance and perfection, his beauty. For European artists informed by a strong sense of this, the task has typically been to keep their work transparent to that brightness, by one route or another. What once Gothic stained glass delivered, William Blake and later Cecil Collins strove for with the translucence of staining inks on paper, and for that matter pious Victorians such as William Holman Hunt worked to the same end with the glazing of their oils.

But we are a long way from Gothic stained glass, and the emergence in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries of a category of taste that came to be labelled ‘the sublime’ is a marker of that distance. Other papers in this Tate Research project discuss the historical relations between that emergence and the process of secularisation. My own extremely simplified formula would be that art itself as a cultural category had progressively established an autonomy, vis-à-vis religion, during the Renaissance, and that afterwards this new sub-category of the sublime arose as a way of sealing the separation, for it enabled its users to redesignate any impulse that headed towards the transcendent as an affair of purely human ‘taste’. (Pseudo-Longinus, the antique writer who for us is the originator of the sublime, describes the ‘Let there be light’ of the Bible as an effect of authorial good judgment on the part of Moses.24) The more a notion of the sublime is entrenched and absorbed, the less it becomes possible for new artworks, however full of spiritual aspiration, to pretend to a publically defined, distinct religious function. That is why whatever thoughts I may have had about Hell while painting Darvaza, my big canvas for a public art gallery, could only be as it were in play.

There is nothing to stop an artwork maintaining an indistinct spiritual availability – witness the popularity of Rothko’s Seagram murals 1958–59 (Tate) and more recently of Bill Viola’s video triptychs and James Turrell’s presentations of pure light. Currently ‘the spiritual’ is a category a whole degree more vague than the sublime – with which to be sure in these cases it overlaps. ‘The spiritual’, a category contemporary art can more or less share space with, really just amounts to an ever-latent inflection of consciousness. The religious, a category it effectively cannot, is about something, or rather someone, namely God.25

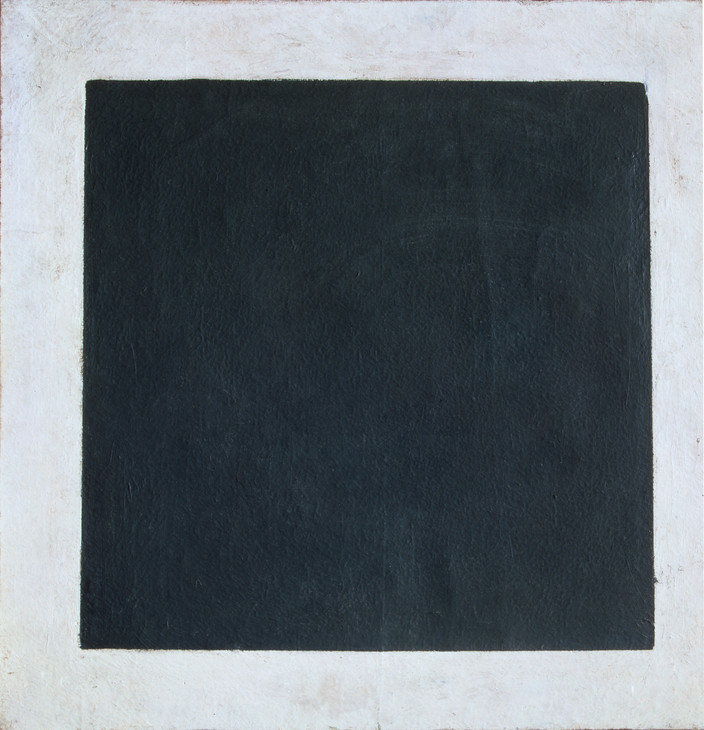

Kazimir Malevich

Black Square 1930

Oil on canvas

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

© The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin, Leonard Kheifets, Yuri Molodkovets.

Fig.11

Kazimir Malevich

Black Square 1930

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

© The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin, Leonard Kheifets, Yuri Molodkovets.

Nonetheless, various strands in the intrinsically extra-religious art of the sublime might correspond to various ways of religiously approaching God. One, the subject of much exegesis, is the via negativa, the attempt to come to God by way of what he is not. Interpreters of modern painting have been fond of characterising any blocked-off vista, or any point at which expression-driven brushwork collapses into the muteness of ‘mere paint’, as an analogue for a failure to discover the divine within the visible – or even as an attempt to jump the viewer into his own spiritual crisis. To come at this critical line reductively, all that is being reconfirmed here is that painting (in parallel, famously, with British politics) ‘doesn’t do God’. But painting has a predisposition to dual effects and paradoxical: at its mutest it is liable to be at its most eloquent; its darknesses may dazzle. Witness the archetypal modernist moment of 1915, Kazimir Malevich painting his Black Square (fig.11)while rhapsodically declaring that, through this ‘zero of form’:

I have destroyed the ring of the horizon and escaped from the circle of things ...

I have released all the birds from the eternal cage ...

I have untied the knots of wisdom and set free the consciousness of colour! ...

I have overcome the impossible ...26

I have released all the birds from the eternal cage ...

I have untied the knots of wisdom and set free the consciousness of colour! ...

I have overcome the impossible ...26

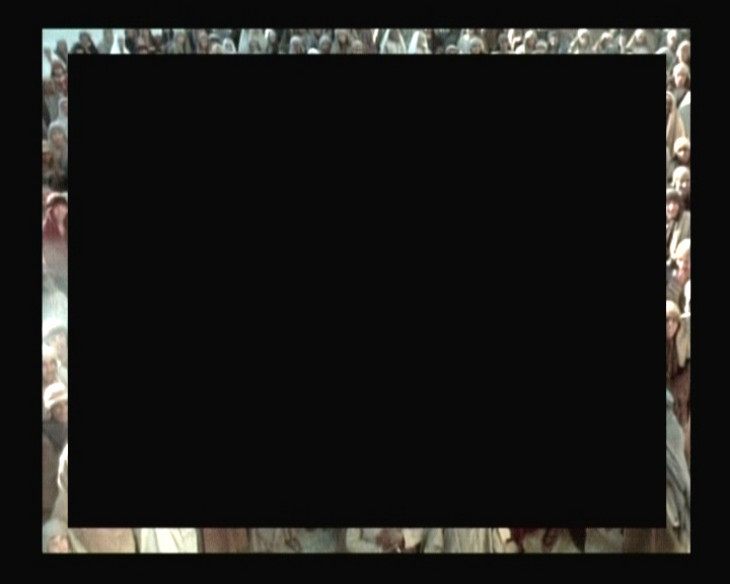

Even if contemporary art cannot be positively and substantively religious, it might provide a forum in which to consider this very problem. This is what Mark Wallinger did during the 1990s and 2000s, using a variety of tactics, from statuary to video. His Via Dolorosa 2002 (fig.12) is by genre a typical specimen of appropriation art: Wallinger laid claim to sixteen minutes of footage from Jesus of Nazareth, a reverent and highly popular film for television made in 1977 by Franco Zeffirelli. His concept was to black out the centre of the screen, leaving only a fringe of visible image, a picture that is in effect a frame. In the watching, Via Dolorosa is an experience of frustration. A salutary frustration? Are we thereby brought to the brink of sublimity, induced to contemplate the unpicturable pain of the crucifixion? A supercilious frustration? How dumb of Zeffirelli to translate divine mysteries into a florid picturesque: how much smarter this latter-day re-edit. The exercise is almost insufferably poised, not least in its arch nod to the Malevich modernist icon mentioned above; and yet it somehow obtains the benefit of the doubt. Wallinger would not have wanted to do it, if he had not wanted to think about something seriously.

***

We have looked at various formats in which contemporary art attempts effects that Edmund Burke might have recognised as sublime, and we have looked at certain types of content they might involve. The various issues we have touched on bear on a larger issue – what claims contemporary visual art can make for its own cultural centrality: why should it be accorded such titanic architecture and such an exorbitant status as a form of financial investment? Evidence, such as that assembled above, might be brought out in response, as a way to refute any allegation that the scene represented by and revolving around the Tates, the Guggenheims, the MoMAs and all the art fairs and biennales is petty, trivial or timid in its concerns. On the contrary, as I have tried to show, it is not only that we have this great big bag called art – this massive cultural kennel, this monster cage. It is that when we talk about the contemporary sublime, we are very largely talking about the way that artists have tried to fill that bag with appropriately huge subjects. (Or at least, very big-looking beasts, whether or not they really bite.)

The sublime as it gets spoken

That said, it is doubtful whether any of the artists mentioned above would care one way or the other whether or not they were described as exponents of the sublime. They might be willing to adopt the term as a convenient presentational hook, but most of them would probably regard it as a curatorial device, incidental to their real working concerns. Speaking for myself, I was peripherally aware that the label might be invoked when people looked at my painting Darvaza, but if anything I rather hoped that it could be avoided. And this was because it might involve me in an ongoing critical wrangle as to the definition of the sublime – the very thing, in fact, that has come to pass as I write this. In this second section, I will try to disentangle the verbal complications I had been holding at bay, approaching the sublime through those who have consciously given shape to the theme rather than through those artworks that merely happen to reflect it.

A genealogy of the contemporary sublime: Newman to Lyotard

‘The sublime’ is a concept, and concepts belong more properly to writers who theorise than to makers of things to look at. Yet some individuals straddle both categories. One, notably, was Barnett Newman, a philosophically educated controversialist who drafted the article ‘The Sublime is Now’ in 1948 in a bid to position his fellow New York painters in contrast to the European tradition. The latter had been overwhelmingly fixated on beauty, Newman claimed, whereas he and his friends pitched their new art at ‘the absolute emotions’. ‘The image we produce is the self-evident one of revelation, real and concrete’,27 he asserted, bombastically and paradoxically equating transcendence and physicality. But then a kind of God-shy spiritual presumptiveness posited on large and simply constructed artefacts would become Newman’s habitual arena. His activities epitomised the trait the philosopher James Kirwan ascribes to post-Romantic thought in general: ‘the aspiration of the self to lift itself up by its own bootlaces.’28 Newman went on two years after his essay to entitle his vastest canvas to date Vir Heroicus Sublimis 1950–51 (MOMA, New York). His rhetoric echoed the thinking of his sometime associate Clyfford Still and to some extent that of Mark Rothko; but Newman’s invocation of the sublime did not, as far as I can trace, result in the term joining the studio lexicon of 1950s painters.

Instead, it got reshuffled by the inventively revisionist New York art historian Robert Rosenblum. Rosenblum published an essay on ‘The Abstract Sublime’ in 1961, incorporating its arguments into an engaging and widely read book, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko, in 1973. As the title indicates, Rosenblum argued that Newman’s generation did have European forebears, only they did not come from Italy and France – the motherlands of beauty, sensuality and good taste, those qualities that Newman scorned. The art historian’s eye traced a certain vein of sensibility that runs from early nineteenth-century German landscapes in which the horizon – the limit of the visible – is forcefully symbolic, through Van Gogh, Munch and Klee to abstract expressionist canvases in which there is an equally emphatic reaching out to the ultimate. Rosenblum described a pictorial sublime that had been a means for two centuries of artists to ‘seek the sacred in a modern world of the secular’.29 A great deal of landscape-based painting and photography has been created in awareness of his book from the 1970s onwards, and to that extent an account of values acknowledging the sublime did re-enter studio currency.

In 1982, many artistic revolutions onwards from Newman’s invocation of the sublime in 1948, a totally separate interpretation of his rhetoric appeared.30 Jean-François Lyotard was a Paris-based philosopher in his late fifties who had participated in the dramas of the French left over previous decades and who remained intent on igniting radical, oppositional momentum – as a conceptual possibility, at least. Three years earlier an analysis of the cultural dynamics of the age, The Postmodern Condition, had brought him fame. The ‘postmodern’ that Lyotard presented was marked by a collapse of cohesive ‘grand narratives’ and as such was a development to embrace, since regimes on every level – political, cultural, epistemological – needed to be confronted with their own limits, the borderlines at which they ceased operating. It was a potential to deliver this sort of confrontation that Lyotard discerned in Newman’s artworks, linking them to works by Cézanne, Duchamp and Malevich as exemplary moments in the history of the avant-garde. Lyotard built on the fact that Newman had employed a term theorised by Kant, the philosopher to whom he himself most often returned.

Lyotard argued – through a succession of essays and the curation of a 1985 Paris exhibition – for an art of the sublime that was concerned with ‘presenting the unpresentable’.31 Certain radical, abrupt, uncompromising artistic acts might actively refuse to be understood – refuse to fall within known narratives and schemes of meaning – and might thereby confront viewers with their own conceptual limitations. Such avant-gardism could deliver the vitalising mental shock that Kant believed inherent in the experience of natural sublimity – of ‘threatening rocks’, ‘thunder clouds’ and ‘the boundless ocean’.32 It might interrupt the continual ‘destruction of experience’ in which the homogenising processes of global capitalism involve us. The stark verticals on which Newman’s artworks depend – his trademark ‘zips’ – provided Lyotard with one such sudden rush; Malevich with his irreducible Black Square supplied another.

Lyotard’s theorisations of the sublime (which ran alongside other French academic work on the theme, less concerned with contemporary art33) were meant to relate, at least implicitly, to a positive, proactive politics. If they were of a piece with his own account of the ‘postmodern’, they stood in declared opposition to a more common 1980s interpretation of ‘postmodern art’ – the ‘mix it up, anything goes’ version, one might say. As to ‘the painting that’s now generally referred to as “postmodern”’, Lyotard stated in a 1985 interview,

I can only say that it strikes me rather unfavourably. These forms of painterly expression that one now sees returning, these transavantgardists, or let’s say neoexpressionists ... seem to me to be a pure and simple forgetfulness of everything that people have been trying to do for over a century: they’ve lost all sense of what’s fundamentally at stake in painting. There’s a vague return to a concern with the enjoyment experienced by the viewer.34

This is what happens when scratchy ageing philosophers decide to address themselves to the theme of art: they not only avoid the tiresome business of actually looking at artworks, they make it their business actively to disparage it. By the same token, there was no particular form of visual sensibility that Lyotard appeared to advocate, while he clove to his lineage of verbally articulate avant-gardists. And thus an intellectually imposing, politically stirring description of ‘the sublime’ entered into international ‘artspeak’ – its importation reflecting a widespread 1980s vogue for French theory – as a joker in the pack: from Black Square to carte blanche.

A genealogy of the contemporary sublime: Kelley to Tuymans

As of the early 1980s, many a campus beyond Paris was acquainting students with the concept of the sublime. Emerging from CalArts, the trans-media arts institute outside Los Angeles, Mike Kelley used the term as the title of a Longinus-citing performance in 1984. Transgressive performances, erudite texts, crude drawings, sculptural installations and post-punk amplified noise all came together in the work of this bricoleur-provocateur, with his focus on the truths that might be exposed via base materials, ranging from recycled soft toys to excrement. Kelley’s imaginative world turned around working-class life in his hometown of Detroit, and as such his sublime was very much an affair of the street, of youth culture. The limit point to articulate thought did not come from mountains and oceans. ‘For me,’ Kelley reflected in an interview,

psychedelia was sublime because in psychedelia, your worldview fell apart. That was a sublime revelation, that was my youth, and that was my notion of beauty. And that was a kind of cataclysmic sublime. It was very interiorized, it wasn’t about a metaphysical outside; it was about your own consciousness. That’s my starting point of the sublime.35

Kelley went on to suggest that such a sublime could be produced by ‘image clash, image resonance, things like that’.36 An instance would be his Silver Ball 1994 (fig.13), a big unshapely scrunch-up of cooking foil and chicken wire suspended above a gallery floor and attended by a sound system and baskets of plastic fruit. The UFO-esque anomaly is desperate to be ‘weird’, is desperate to be worshipped, is desperate, period; and in this has a kind of sad integrity. Such a bathetic endpoint of meaning locates the sublime once again in adolescence with its familiar terrains of science fiction, drug-taking and intensive, abrasive noise. Another artist emerging from the 1980s LA scene, Fred Tomaselli, offered a comparable interpretation: ‘In my life I have only ever been able to access the sublime chemically ... It’s a major subject in the history of art and it also happens to be the major component around drugs.’37 Tomaselli’s paintings, however – literally pill-studded variations on the final, ‘Beyond the Infinite’ sequence of Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey – are defiantly, exultantly (and self-consciously) whimsical in their subscription to mind-alteration.

They offer a wilfully naive descant on a scene in which bathos and shamefulness had come to the fore. The late 1980s and early 1990s were the heyday of the grunge movement in rock and of its art world equivalent, the vogue for ‘the abject’. Exhibitions dealing in blood, shit or viscera would habitually reference the Paris-based theorist Julia Kristeva and her 1982 book Powers of Horror. Kristeva took her cue (as to a large extent did Kelley) from Freud and his notion of the unheimlich or uncanny: the object which disturbs because it brings an individual into contact with matters that he or she has repressed. The overall shape of such a pattern of repression, for Kristeva, was an individual’s ‘symbolic order’, the foundation of their own self-definition – the abject being whatever it excluded. Kristeva found feminist and indeed more general political implications in this formula, which readily fell in line with the notion of the sublime as a limit to the comprehensible. It equally spoke to would-be avantgardists who sensed that their tradition had arrived at a defensive, dejected, historical low ebb.

Between Lyotard’s visually unspecified call-to-disorder and Kristeva’s backhanded picturesque of the repellent, between mass society’s ever-latent groundswells of spiritual dissatisfaction and articulate artists such as Kelley and Tomaselli who were finding new ways to emblematise them, there was every reason why ‘the sublime’ should prove a very convenient curatorial hook for a growing number of exhibitions from the early 1990s onwards, the tag being archly extended in many an ingenious direction. For all the thinkers I have just named, whatever was sublime must inevitably offend against taste – against, that is, received ideas of aesthetic decorum and discursive etiquette. And yet such exhibitions spawned their own loosely defined taste zone, proposing what might be an appropriate sensibility, what type of image-stock to use.

The catalogue illustrations to The Sublime Void, a show held in Antwerp in 1993, return repeatedly to emptied vessels (for example Rachel Whiteread’s object casts, or the dangling coats of Juan Muñoz ) and to forlorn, anomalous vestiges (Robert Gober body parts, Thomas Schütte putty figurines). The window-picture that is veiled or blurry (as in the paintings of Gerhard Richter) and the blocked-off receding road (as in the photos of Willie Doherty) would be co-opted in other exhibitions for the same triste symbolism of spiritual disappointment – often associated, as I indicated above, with the theologians’ via negativa. Back in Barnett Newman’s day, the sublime had still bristled with hunky machismo: no longer. It was now reassigned to keep company with ‘the trace’, that wistful sigh of the intellect so cherished by poststructuralist theorists.

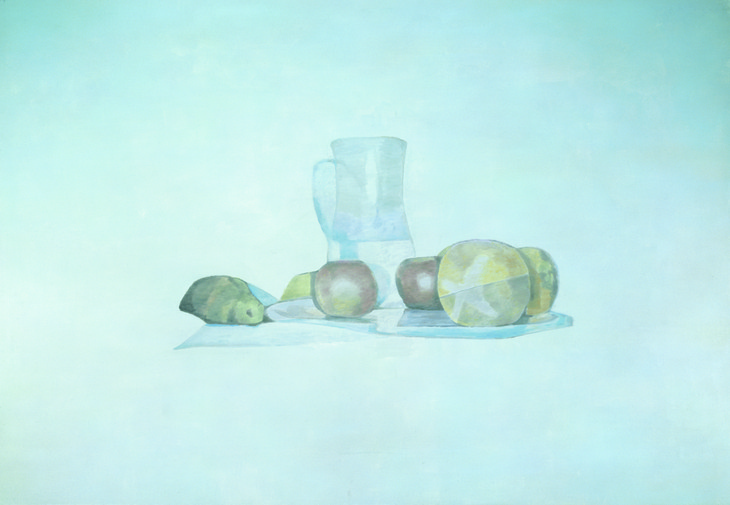

Luc Tuymans

Still Life 2002

Oil on canvas

3470 x 5000 mm

© Luc Tuymans, 2002

Image courtesy of The Saatchi Gallery, London

Fig.14

Luc Tuymans

Still Life 2002

© Luc Tuymans, 2002

Image courtesy of The Saatchi Gallery, London

The sheer scale makes the contemplation of this painting almost impossible: a vast canvas representing an absolute nothingness. Luc Tuymans chose the subject of still life precisely because it was utterly unremarkable; a generic ‘brand’ of ‘object’ rendered to immense scale; it is banality expanded to the extreme. The simplicity of Luc Tuymans’s composition alludes to a pure and uninterrupted world order; the ephemeral light, with which the canvas seems to glow, places it as an epic masterpiece of metaphysical and spiritual contemplation. In response to unimaginable horror, Luc Tuymans offers the sublime. A gaping magnitude of impotency, which neither words nor paintings could ever express.39

Tuymans himself positions his values on another level:

I’m not so much interested in the spiritual aspects of culture – ‘beauty’ or poetic descriptions of beauty don’t seem real enough for me. Reality is actually far more important than any form of spirituality. Realism. It’s much more interesting to crawl from underneath to the so-called top.40

To this author, both statements seem deeply misleading. Tuymans’s paintings gained their reputation owing to the fact that they are, in a melancholic fashion, extremely beautiful. Like the Belgian Symbolists of an earlier era – Fernand Khnopff, Léon Spilliaert – he revels in the poetry of cold, November-afternoon pastel tones and seems incapable of delivering an inelegant brushmark, even on the rare occasions when he tries. A fine judgment about how far to diminish and distance his motifs has been crucial to Tuymans in his attempts to conjure a frisson of menace from such exquisiteness. It deserted him as he worked up his response to the loud public agenda of 9/11: the result is neither ‘extreme’ nor ‘epic’, merely vapid and inert. In this case the vogue for the sublime delivered not merely inflated verbiage, but pretentious art.

The limits of the sublime

Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry and in its wake Kant’s Critique of Judgment each consistently distinguished the sublime from the beautiful, treating both categories as forms of ‘taste’, that is to say of aesthetic experience. The aspects of recent art practice and discourse that I have been reviewing return me to these distinctions, making me want to reconsider them. Can the sublime in art, I might ask, also at once be the beautiful? Can the controlled-uncontrollable, or presented-unpresentable, that which pushes me to teeter one foot over my mental cliff-edge, somehow bed down comfortably within the zone that we simply term ‘taste’? – good taste being aesthetic experience that meets with contemporary social approval.

Or rather, perhaps I should ask: how can they not? How can any sublime that is presented through art not get bound up in the take-it-or-leave-it luxury of spectatorhood, how can it not be complicit in sheer showmanship? Surely Kant was right to dismiss artworks from consideration in his analysis of the sublime, instead positing his aesthetic on experiences of nature? By 2001, when Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe published Beauty and the Contemporary Sublime, the institutionalisation of a concept that in Lyotard’s hands had been definitively anti-institutional was already a given. Gilbert-Rolfe contrarily proposed (as far as I can tell) that nowadays it was the category of ‘beauty’ (idiosyncratically defined) that was truly radical and liberatory. A short sample of the book’s argumentation may suggest why it failed to resolve the issue to universal satisfaction:

The extreme mobility of the contemporary sublime erodes autonomy because it calls for movement through the heteronomous which is itself heteronomous, provisional singularity taking the place of the irreducible, movement being the basis of the indeterminacy of what is erased and represented within it.41

The book was in fact the occasion for Thomas McEvilley’s riposte, quoted earlier, that if contemporary art was looking for a genuine challenge to its prevailing modes of representation, then it needed to peer out of the gallery window at the vast and fearful unknown of global capitalism: only that way could the sublime regain ‘its old dignity and danger’.42

My impressionistic survey has tried to demonstrate, however, that artists themselves are not to be collectively arraigned for a failure to think seriously. A truth-seeking instinct seems to be a permanent feature of our mental equipment, and it reveals itself in any number of contemporary art initiatives. Axiomatically, we cannot foretell what truths these artworks might arrive at, or whether in fact they will arrive at any. The whole zone called ‘art’ is in many senses a fictive space, and to push at this limitation is bound to involve the artist in paradoxes. The critic and curator may in turn wish to round up any number of those paradoxes – those presentations of the unpresentable – within the category of the sublime.

It is just that, as of 2012, the process of rounding up feels to have gone a little too far. As a painter – a dealer in surfaces, a literally superficial individual – I need to keep in mind some look that distinguishes what is sublime from what is not. For me, it does not seem useful to include in the category art that employs the whole human figure as its central property. Art that describes the human figure in completed relationships is surely outside the province also. Individuals in relation to interiors they inhabit and in their social interrelations make poor candidates for the sublime, and by extension associated subject-matters – whether we are talking about identity issues and political contestation, or pastoral landscape and still life – are not well described in this way. (It is true that any of these prescriptive guidelines might be overturned as soon as an artist reaches out for extremes of scale.) Completed relationships on a formal and abstract level are obviously non-sublime. Donald Judd, Patrick Caulfield, Sophie Calle, Thomas Hirschhorn: these are all in their differing ways exemplary artists of the non-sublime. How far to gather them up within the attractive enclosure of the beautiful, I leave to others.

That still leaves rather a vast amount of contemporary art stuck in the bracing cold outside. And I think the point has been reached where a blanket description for these aesthetic asylum-seekers will no longer do. The critical border police need to find superior methods of discrimination.

Notes

For example in Lee Rozelle, Ecosublime: Environmental Awe from New World to Oddworld, Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2006.

For example in the essay of that name by Vijay Mishra, in Simon Morley (ed.), The Sublime: Documents of Contemporary Art, London 2010.

For example in the photographer’s website http://www.jeremyhogan.name/portfolio/11/military-industrial-shopping-complex , accessed 18 September 2012.

For example in the artworks of James Turrell, Damien Hirst, Luc Tuymans and Mike Kelley respectively.

Jonathan Jones, ‘Julian Bell, Joseph Wright and Britain’s Titian Triumph’, Guardian, 2 March 2012, www.guardian.co.uk/.../2012/.../julian-bell-joseph-wright-art-weekly , accessed 18 May 2012.

Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, 1757, Part 2, Section IV.

‘The sheer effort to build these things has a lot to do, finally, with what they’ve become’, Serra acknowledges. Ibid., p.301.

My belief that the opposition to Tilted Arc stemmed from a genuine groundswell of popular opinion rather than from politicians’ contrivances is based on conversations with New York residents, including members of the arts community.

Comments made in the film Anish Kapoor Marsyas 2002 theEYE: Anish Kapoor: www.youtube.com/watch?v=m1Ouyhjx06k , accessed 19 September 2012.

Matthew Ritchie | Apocalypse | Art21 Blog: blog.art21.org/2008/08/21/matthew-ritchie-apocalypse/, accessed 18 May 2012.

Jorge Luis Borges, ‘The Library of Babel’ (1941), opening sentence: this translation by James E. Irby in Jorge Luis Borges, Labyrinths (1964).

For example Caroline Levine, ‘Gursky’s Sublime’, pmc.iath.virginia.edu/issue.502/12.3levine.html, accessed 19 September 2012.

A lively, shrewd and deeply informed survey of these issues is available in James Elkins, On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art, Routledge, 2004: see in particular pp.95–100 for a discussion of the sublime.

Kazimir Malevich,text to accompany ‘The Last Futurist Exhibition’, 1915: translation as included in C. Harrison & P. Wood, eds, Art in Theory: 1900–1990, Oxford 1992, pp.166–176.

James Kirwan, Sublimity, London 2005, p.155. Kirwan’s book is the sharpest history of modern concepts of the sublime that I have read, wide-ranging and written with philosophical wit and discrimination.

Robert Rosenblum, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko, London 1978, p.218.

Jean-François Lyotard, ‘Presenting the Unpresentable: The Sublime’, translated by Lisa Liebmann, Artforum April 1982, 20(8): pp64–69.

Bernard Blistène, ‘Les Immatériaux: A Conversation with Jean-François Lyotard’, Flash Art, no.121, March 1985.

Mike Kelley, interview with Art21, 2005: www.art21.org/.../mike-kelley/interview-mike-kelley-language-and - ..., accessed 18 May 2012.

Fred Tomaselli and Philip Taaffe in conversation with Raymond Foye and Rani Singh, 2002: www.philiptaaffe.info/Interviews.../Tomaselli-Smith-Taaffe.php , accessed 18 May 2012.

Luc Tuymans, BBC Radio 3 interview with John Tusa: www.bbc.co.uk/radio3/johntusainterview/tuymans_transcript.shtml , accessed 18 May 2012.

Saatchi Gallery website: www.saatchi-gallery.co.uk/artists/luc_tuymans.htm , accessed 18 May 2012.

Julian Bell is a painter and writer.

How to cite

Julian Bell, ‘Contemporary Art and the Sublime’, in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication, January 2013, https://www