Artistic Responses to the Lebanese Wars

As the final section of On Three Posters makes clear, the original performance was produced with a Beirut audience in mind, one that would understand the nuances of the ‘Lebanese Wars’. As Mroué makes clear in ‘Travel and Translatability’, Three Posters was explicitly concerned with the Lebanese historical context; the artist worried about European audiences’ ability to understand a history that was too complex to be summarised and stopped performing the work when it became clear that responses to the attacks on the Twin Towers in New York in 2001 foreclosed any possibility of insisting on a Lebanese specificity. This insistence on Lebanese specificity is relevant not only to Mroué’s video but also to the way in which we can understand his position within a larger generation of Lebanese artists.

With their contradictory alliances, constantly shifting roster of combatants, and competing accounts, the civil wars remain a topic of obfuscation, denial and lingering antagonism within contemporary Lebanese society. This is reflected in the state’s handling of war crimes and in the undetermined fate of the estimated 18,000 Lebanese who went missing during the fifteen-year period. Following the signing of the Taif Accord in 1989, marking the formal cessation of hostilities, the Lebanese government passed an amnesty law effectively granting any former members of militias exemption from criminal prosecution.1 According to the official discourse of the newly reformed state, the amnesty law was predicated on turning the page of the past and starting a new one in the name of national reconciliation. The legal measure was prompted by the fear that any investigation of crimes perpetrated during the years of sectarian conflict would awaken grudges and undermine the peace process if they remained on the table for discussion and debate. However, the imposition of the amnesty law led to the complete absence of serious governmental or civil initiatives to deal with the past, whether in the form of a national dialogue or a public enquiry into the fate of the missing. Elias Khoury observed in 2006: ‘The new post-war political class – warlords and war criminals in alliance with oil-enriched capital and military and security apparatuses – was able to impose an amnesia, a complete forgetting, in order to whitewash their innocence. Their victims were silenced.’2

Working across the fields of photography, video, and live performance, a generation of artists who grew up during the wars and who have directly shaped each other’s practices – including Lamia Joreige (born 1972), Walid Raad (born 1967), Walid Sadek (born 1966), Lina Saneh (born 1966), and Akram Zaatari (born 1966) – have made artworks that provide platforms for the critical examination and recovery of collective memory in Lebanon.3 By conducting archival research, unearthing ephemeral artefacts, and collecting eyewitness testimonies, these artists seek to bear witness not only to the physical violence of the recent past, but also to the mnemonic damage caused by it. The difficulty in representing the events of this history not only concerns the problem of determining what happened based on fragmentary and tendentious evidence. It also has to do with the discrepancy between the immediate violence of protracted war and the incapacity of subjects to narrate their experiences in larger collective terms. At the same time as it has taken up fraught questions of traumatic memory, this generation of artists working in Beirut has sought to shift the focus away from an imagery that casts the Lebanese, in the words of philosopher Jacques Rancière, ‘as eternal victims of war’. Thus, rather than confine their gaze to images of war, they are more interested in ‘what the war did to the images’.4

This generation of artists has been seen by curators and critics both in Lebanon and the West as miraculously emerging from the ashes of a war that witnessed the destruction of Beirut’s image as a cosmopolitan capital for Arab cultural and intellectual production.5 This monolithic alignment of the artists around questions of war, trauma, and memory threatens to ignore the diverging and sometimes conflicting ways in which these artists represent the events of the recent past. Recognising this danger, and without treating these artists as a unified group, however, we can nonetheless say that there are a number of thematic and methodological procedures that link these practices together.

Mroué and his artistic compatriots have produced work premised on the recognition that the traumatic effects of war manifest themselves most tellingly after the fact. As such, their art is concerned less with the manifest injuries of war than with its lingering effects. In fact, these practices can be seen to engage in a compulsive repetition of the recent past that is neither therapeutic nor cathartic but productive all the same, precisely in the space that it opens up for a working through of traumatic memory. Going a step further, it could be argued that in Lebanon artistic re-enactment serves to bear witness to a past that was never fully experienced at the time it occurred. Literary scholar Cathy Caruth comments in her elaboration of psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s study of war neurosis: ‘trauma is not locatable in the simple violent or original event in an individual’s past, but rather in the way that its very unassimilated nature – the way it was precisely not known in the first instance – returns to haunt the survivor later on’.6 From a Freudian point of view, then, a traumatic event paradoxically remains in a deep structural sense unavailable to the subjects who experience it. As such, it is only retroactively, in the unconscious symptom formations of the survivor, that the event is experienced at all.7

Mroué’s ‘chance’ re-discovery of Sati’s tape almost fifteen years after it was made raises an important question: what rights do the living have over images of the departed? In fact, the question might be reversed: what claims do the dead make over the survivors of a war? For here we are dealing with images that do not simply capture a fully resolved moment in the past but rather resurrect a dormant and unprocessed history. The artists Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joriege have theorised this oscillating and ambiguous relations to traumatic images that have emerged or resurfaced since the formal conclusion of the civil war around a psychoanalytically-informed notion of latency:

The latent image is the invisible, yet-to-be-developed image on an impressed surface. The idea is that of the ‘dormant’ – slumber, slumbering– like something asleep, which might awake at any moment. Latency has connotations with essence, but also with the idea of the repressed, the hidden, the untestable, of an invisible element ... Latency also evokes what is often felt in Beirut, in face of the dominant amnesia prevailing since the end of the war.8

Walid Raad’s Secrets in the Open Sea 1994, a work that consists of what appear to be a series of abstract prints of varying shades of blue, explicitly addresses the notion of images that exist in ‘a state of latency’(figs.1 and 2).9 The text accompanying these images states that they were found in 1992 under the rubble of demolished buildings in the Souks area of Beirut and given for examination to the Atlas Group (the identity under which, until 2008, Raad exhibited most of his art). When the Atlas Group sent six of the prints to a laboratory in France for analysis, it was revealed that they each contained ‘latent images’ hidden beneath the surface. These images (small black-and-white group portraits of men and women) were identified as individuals who ‘drowned, or were found dead in the Mediterranean between 1975–1991.’10 The marginalisation of the black-and-white images, dominated by the more abstract blue shades, suggests that a photographic image cannot provide direct access to history. Instead of taking for granted the existence of the archival image of death, the Atlas Group’s work raises questions about how such an image might be recovered at this point in history.

Walid Raad

Secrets in the Open Sea 1994 (plate 16)

1110 x 1730 mm

Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Photo © Walid Raad

Fig.1

Walid Raad

Secrets in the Open Sea 1994 (plate 16)

Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Photo © Walid Raad

Walid Raad

Secrets in the Open Sea 1994 (plate 16, detail)

Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Photo © Walid Raad

Fig.2

Walid Raad

Secrets in the Open Sea 1994 (plate 16, detail)

Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Photo © Walid Raad

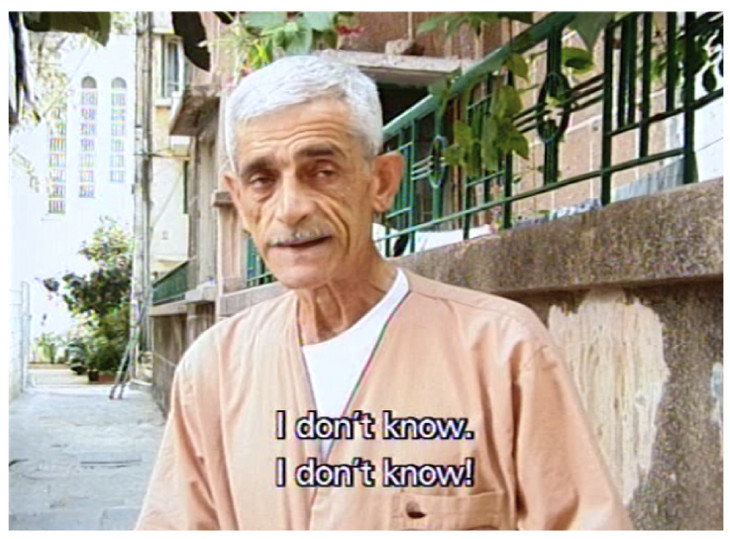

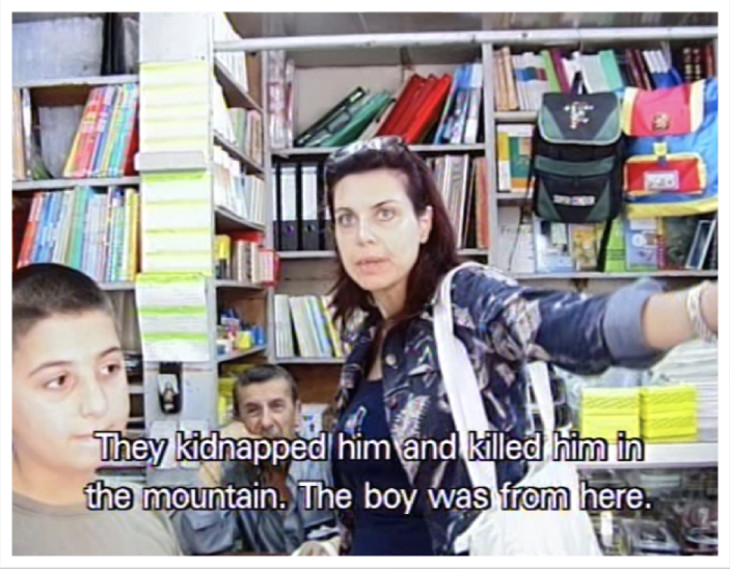

Another work that explicitly foregrounds the symptoms of traumatic memory and questions the living’s responsibility to the dead is Lamia Joriege’s Here and Perhaps Elsewhere 2003. This video documents a non-linear journey through the neighbourhoods adjoining the Green Line, the demarcation line that once separated east and west Beirut during the Lebanese wars. In the video Joreige walks through the city spaces, approaches residents, and asks them each the same question: ‘Do you know anyone who was kidnapped from here during the war?’ The question serves as a trigger, producing responses that range from callous indifference and startling admissions to aggressive denial (figs.3 and 4). Joreige’s art is not concerned with producing a moral judgment of human actions. Nor is it concerned with uncovering the final truth of these events. Indeed, one man in the video bluntly says of the testimonies gathered by the artist, ‘there’s no reason to record them, because they may be true, they may not. And they won’t give you the answer you’re looking for’. Yet Joreige’s question clearly touches open wounds, placing the artist in a double bind that admits to no easy solution. On the one hand, her intervention into these spaces seeks to counter the forms of repression, paranoia, and censorship that surround the subject of missing persons in Lebanon but, on the other hand, the video reveals that the interrogation of the past might itself be traumatic. Indeed, at some points Joreige’s line of enquiry seems to violate the respondents’ rights to forget painful episodes from their past.

Lamia Joreige

Here and Perhaps Elsewhere 2003

Still from video

© Lamia Joreige

Fig.3

Lamia Joreige

Here and Perhaps Elsewhere 2003

© Lamia Joreige

Lamia Joreige

Here and Perhaps Elsewhere 2003

Still from video

Photo © Lamia Joreige

Fig.4

Lamia Joreige

Here and Perhaps Elsewhere 2003

Photo © Lamia Joreige

At the end of the video Joreige has a chance encounter with a woman who knew the artist’s uncle Alfred Kettaneh Jr., who went missing on 19 August 1985 while driving a Red Cross ambulance across the Green Line. The circumstances of his disappearance remain a mystery. The family can only assume that he was kidnapped and murdered, but without a body or any witnesses there is no way to determine what actually happened to him. Under Lebanese Law a person ‘whose whereabouts are unknown and of whom no one knows whether he is dead or alive’ can be declared deceased four years after his or her disappearance.11 The law places the burden on the family of the missing since it is they, rather than the state, who must request a hearing on the matter. Yet in the absence of any evidence can such a ruling provide real closure for the relatives of the missing? By the same token, do the relatives of the missing have an obligation to wait for the return of someone who will most likely never come back? These questions also resonate in Khalil Joreige’s and Joana Hadjithomas’s film A Perfect Day 2005, the narrative of which centres on the strained relationship between a mother, Claudia, and her son Ziad. Both are haunted by the unexplained disappearance of Ziad’s father fifteen years earlier. At the beginning of the film Claudia appears to rush Ziad into signing papers that would declare her husband legally dead. However, before the declaration is finalised the two must provide their lawyer with newspaper announcements attesting to the man’s disappearance. As the day progresses it becomes apparent that Claudia is not ready to close this chapter even if it means putting her own life perpetually on hold. This is expressed in an anxious monologue that she delivers next to the sleeping Ziad: ‘If he comes back tomorrow, what would he say? Tomorrow or the day after. If he ever came back and asked us, “Why didn’t you wait longer for me? Why did you stop waiting?”, what could we say?’

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige

Excerpt from the fictitious notice of disappearance inserts in newspapers, reprinted for the purpose of the film A Perfect Day 2005

Courtesy the artists

Fig.5

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige

Excerpt from the fictitious notice of disappearance inserts in newspapers, reprinted for the purpose of the film A Perfect Day 2005

Courtesy the artists

Mroué and the artists discussed here are not interested in providing autobiographical accounts of their war-time experiences (see the author’s interview with the artist). One reason for this has to do with their refusal of the indignity of victimhood. The second concerns their belief that the witnessing of a violent past disrupts the very existence of a coherent self that could be expressed in language, whether visual or verbal. The ‘I’ that appears in their work is one that more often than not has an invisible set of quotation marks around it. When he speaks in the first person, Mroué should be understood to be performing a role. Yet it would be wrong to say that biography does not in some way inform some of these practices.

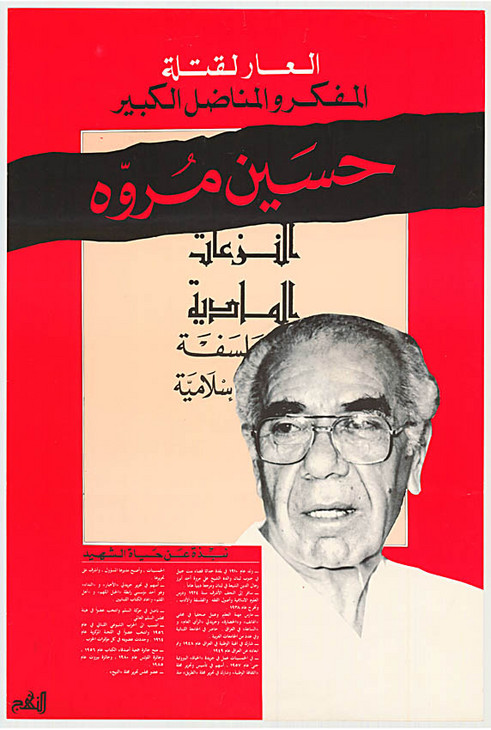

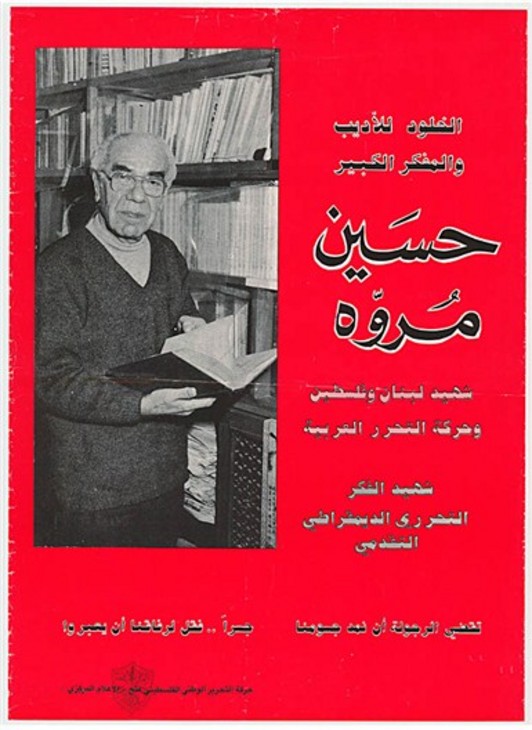

In Three Posters the weight of personal history was also deeply entangled with the troubled political history of the nation. In the second half of the 1980s the Syrian regime of Hafez al-Assad and the Islamic militias who served as its proxies oversaw the systematic elimination of the progressive Lebanese Left. This history forms an unspoken subtext to Mroué’s Three Posters (see also the author’s interview with the artist). The artist’s grandfather, Hussein Mroué, was among the leading intellectual voices of the Lebanese Communist Party (LCP). A member of the central committee of the Party, Hussein Mroué published two substantial volumes on materialistic tendencies in Islam, both of which were considered ground-breaking and highly controversial at the time. On 17 February 1987, while working on the third volume of this project, Hussein was assassinated in his home by two masked gunmen. With no governing authority in place to investigate such crimes or enforce the rule of law, Hussein Mroué’s murder, like countless other cases of its kind, was treated as an unsolved mystery and swept under the carpet. A poster published by the Nahj journal of the Iraqi Communist Party carries the following message: ‘Shame on the murderers of the great thinker and militant Hussein Mroué’ (fig.6). Another poster produced by the Palestinian Liberation Organisation reproduces a photograph of the writer in his library (fig.7). The caption reads, ‘Hussein Mroué the martyr of Lebanon and Palestine and the Arab liberation movement’. Hussein’s death was involuntary yet in these tributes his death is equated with the suicides of martyrs who willingly gave up their lives in defence of their political beliefs.

Poster published by the Iraqi Communist Party in 1987 announcing the murder of Hussein Mroué

Image courtesy of Zeina Maasri

Fig.6

Poster published by the Iraqi Communist Party in 1987 announcing the murder of Hussein Mroué

Image courtesy of Zeina Maasri

Poster published by the Palestinian Liberation Organisation in 1987 describing Hussein Mroué as a 'martyr'

Image courtesy of Zeina Maasri

Fig.7

Poster published by the Palestinian Liberation Organisation in 1987 describing Hussein Mroué as a 'martyr'

Image courtesy of Zeina Maasri

Rather than trying to directly document the events of the war or of their own personal lives, Mroué and his artistic colleagues insistently foreground how memory of the conflict is differently mediated through images that preclude any simple access to ‘the facts’. Al-Sati’s video was undoubtedly a trace of history, but in On Three Posters the tape was also shown to be very much a theatrical performance staged for the camera. This is not to deny the fact of al-Sati’s death (although we cannot be certain of it since we only have the tape and no body) but to recognise that through its artistic appropriation, the self-evident authenticity and immediacy of the video is thrown into question. Conversely, in playing the part of the martyr Mroué drew on aspects of his own life, undermining any clear-cut division between factual document and fictional work of art.

On Three Posters can thus be seen as part of a wider artistic pre-occupation with the uncertain status of images and artefacts in a society that has been traumatised by a history of unspeakable violence. The legacy of the Lebanese Wars cannot only be measured in the remnants of physical destruction or in the biographies of its survivors, including this generation of artists. The wars also changed the way images of conflict were perceived and, more specifically, contributed to a growing sense of their unreality. As Hadjithomas and Joreige note, in the minds of many Lebanese ‘the war had been put into brackets’ as if it did not even happen.13 If Lebanon can be described as a society living in a ‘state of marvellous denial’ about the events of its recent past, then the task of evidencing history through a resurrection of images from the war-era cannot be a straightforward process.14

Notes

The law applies to crimes committed before March 1991, including ‘crimes against humanity and those which seriously infringe human dignity’. Only crimes committed against religious or political leaders could be exempted from the law. These exceptions have mainly been applied to political leaders not in favour with the regime and have therefore been widely denounced as deviations. In comparison, war criminals in other late twentieth-century civil conflicts in Rwanda, South Africa, and Yugoslavia have been subject to national and international trials. For more on the amnesty law see Nizar Saghieh, ‘Dhakirat al-harb fil-nizam alqanuni al-lubnani’ [Wartime Memory in the Lebanese Legal System], in Amal Makarem (ed.), Mémoire pour l’avenir, Beirut 2002, p.225.

Elias Khoury, ‘The Novel, the Novelist, and the Lebanese Civil War’, Fourth Farhat J. Ziadeh Distinguished Lecture in Arab and Islamic Studies, Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilisation, University of Washington, Seattle 2006, p.4. http://depts.washington.edu/nelc/pdf/event_files/ziadeh_series/2006lebanon-eliaskhoury.pdf , accessed 21 November 2013.

Commenting on the closely-knit Beirut art scene, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige note that, ‘between 2000 and 2004, in Beirut we got together with a group of artists every Tuesday (such as Walid Sadek, Bilal Khbeiz, Tony Chakar, Marouan Rechmaoui, Lina Saneh, Walid Raad, Fadi El Abdallah [sic], and others. Rabih was also closely involved. It was a place for exchanging, for sharing, for discussions, for study’. Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, ‘I am Salah el Dine’, in Rabih Mroué, A BAK Critical Reader in Artists' Practice, ed. by Maria Hlavajova and Jill Winder, Utrecht and Rotterdam 2012, p. 85.

‘Lebanese artists like Joana Hadjithomas and Joreige also displace the representation of the Lebanese as eternal victims of war. They are interested not in images of the war, but in what the war did to the images, not in victims or the missing but in disappearance.’ ‘Entretien avec Jacques Rancière’, Les Inrockuptibles, no.679, 2 December 2008.

Examples of this attitude are Nana Asfour, ‘A Cultural Renaissance’, ARTnews vol.98, no.7, Summer 1999, p.76; and Anne Picq, ‘Reportage dans une ville en mutation. Etre artiste à Beyrouth. [A report from a mutating city. Being an artist in Beirut’, Beaux Arts Magazine, vol. 307, January 2010, pp.82–9. On the destruction of Beirut cosmopolitanism, see Elias Khoury, ‘Miroir Brisé’, Beyrouth la brûlure des rêves, ed. Jad Tabet, Paris 2003.

This was the original insight that Freud had made in his 1920 report on the shell-shocked soldiers suffering ‘war neurosis’. See Sigmund Freud, ‘Memorandum on the Electrical Treatment of War Neurotics’ (1920), in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol.17, London, 1955, p.211–15.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, ‘Latency’, in Ghenwa Hayek, Bilal Khbeiz, Samer Abu Hawache (eds.), Home Works: A Forum on Cultural Practices in the Region, Beirut 2003, p.40.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, ‘Latency’, in Ghenwa Hayek, Bilal Khbeiz, Samer Abu Hawache (eds.), Home Works: A Forum on Cultural Practices in the Region, Beirut 2003, pp.40–9.

See Article 33 of the 1995 Lebanese ‘Provisions Relating to Missing Persons’. For a list of amendments to this law see Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, ‘Latency’ in Ghenwa Hayek, Bilal Khbeiz, Samer Abu Hawache (eds.), Home Works, p.49.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, ‘Aida, Save Me’, transcript of lecture-performance, Gasworks, London 2010, p.4.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, ‘Infuences: Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige’, Frieze, no.147, May 2012, pp.166–9.

On this attitude see Bernard Khoury, ‘Yabani R2’, Bernard Khoury / DW5, http://www.bernardkhoury.com/projectDetails.aspx?ID=153 , accessed 23 November 2013.

How to cite

Chad Elias, ‘Artistic Responses to the Lebanese Wars’, February 2014, in Chad Elias (ed.), In Focus: 'On Three Posters' 2004 by Rabih Mroué, Tate Research Publication, February 2014, https://www