Travelling in Italy during Turner’s Lifetime

Ross Balzaretti, Pietro Piana and Charles Watkins

The number of British travellers to Italy in search of health, education and increasingly leisure grew substantially during Turner’s lifetime. Like Turner, travellers recorded their observations in journals and diaries, and some turned their experiences into printed books and guidebooks. This essay examines this material and provides a vivid insight into the rich environment that shaped Turner’s artistic development.

The peace in Europe that followed the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815 led to a surge in the number of British travellers to Italy.1 Napoleon’s armies had developed an infrastructure that included new roads which facilitated the development of cheaper accommodation, opening up travel to a wider range of social groups. Like the pre-Napoleonic Grand Tourists, these later travellers wished to experience Italy, the ‘cradle of western civilisation’, for themselves. In August 1819, as Joseph Mallord William Turner was travelling through France on his way to his first tour of Italy, the artist Harriet Parry was making her way home to Speen Hill, near Newbury in Berkshire.2 She had been away for nearly two months on her ‘Tour in France, Switzerland and Italy’. Her record of this tour still survives in the British Library, written on a narrow roll of cloth-backed paper over five metres long.3 Physically made to resemble a road, it constituted a detailed map of her route, with brief comments on what she encountered, accompanied by a series of tiny postage-stamp sized watercolours reproducing the places she had seen with very considerable skill. No doubt her family would have been impressed by the resulting artefacts, which were intended for them and for her friends.

Parry took the conventional route to Italy through France, via Paris, Burgundy and Chamonix. She journeyed across Switzerland to Milan through the Simplon Pass on the Napoleonic road built between 1801 and 1805.4 She then proceeded to Genoa and Turin, and returned home via Lyons, Tours and Le Havre, arriving in Southampton on 5 August 1819. Parry seems to have had a trouble-free trip if her record of it is anything to go by. Typical of her prose is her highly visual description of travelling from Novi, where she had arrived on 16 July 1819, to Genoa, reached late the following day:

The road from Voltaggio very pleasant in the midst of Appennines [sic] covered with Spanish chesnuts [sic]. Fiery lilies in full bloom in a dell. A zigzag road over the Bocchetta the highest of these Appenines from the top of which is a fine view of the Mediterranean Genoese the road pitched with rough stones and the shaking intolerable towards Campo Marone all the way to Genoa, fine vallies [sic], woods of Spanish chesnuts between the vineyards, and the Mediterranean to the R [right] and deep ranges of wooded Apennines to the left, with palaces and country houses innumerable on the hills.5

It all sounds delightful, apart from the jolting of the carriage, which was the main hazard faced by travellers at this time, particularly on poorly maintained mountain roads. Her engagement with the landscape through which she passed is very evident here. Her comments about chestnuts and the extent of the woodland provide valuable evidence for environmental historians, as many travellers’ descriptions (and drawings) do.6 She had earlier noted that the road from Gavi, ‘passes by, and sometimes thro’ the dry beds of rivers’. These were another potential threat, although not in July when they were at their driest. As we shall see, autumn rains and winter snowmelt could render these extremely dangerous and, indeed, some lost their lives trying to pass them.

In January 1820, as Turner was making his way back north from his first Italian tour, the poet Catherine Maria Fanshawe was on her way to Italy, one of several trips she made there before her death in 1834.7 On her way to Rome, Fanshawe, like Parry, reported her arrival in Genoa to her friend Catherine Maria Bury, Countess of Charleville:

We reached it by moonlight and never shall I forget my surprise in turning a sharp corner of the road after descending the Bocchetta and traversing the long Valley to find myself suddenly upon the very shore of the Mediterranean. Then another turn at the foot of that noble Pharos, rather of the rock on which it towers with such majesty again changed the scene and we swept along the Bay and entered the marble City, the City of Palaces! No palace opens there its hospitable gate to strangers: we were miserably lodged, or perched, on the 6th or 7th storey of a wretched Hotel which we moand [moaned] for the labour but in the incomparable prospect, which commanded the whole bay and from my windows I cd have dropt an orange into the Mediterranean. Oh the Orange Trees! And Oh the beautiful grouping and endless variety of Tower and Dome and Arch and Spire and even at that late season of colouring from the grey Olive to the Pomegranate and the Orange. My green Sketch Book was full at Genoa! I longed [to share feasting?] my eyes amidst all these lovely forms for my sisters’ eyes (which have fingers belonging to them which mine have not) to share and perpetuate the treat.8

Like Parry, Fanshawe was a talented amateur artist who specialised in portraits rather than landscapes, and an even better poet, with a significant reputation by this time.9 Her two sisters Penelope and Elizabeth also drew, and numerous sketches by the latter have survived from a later trip to Italy undertaken by all three in 1828–9.10 Her experience of landscape is also notable in this passage, in particular the implied exoticism of orange trees in fruit.

Parry and Catherine Fanshawe are just two of the many women (and men) who took advantage of the peace after 1815 to travel south.11 The emotional rewards seem to have outweighed the numerous practical inconveniences for most of them. Fanshawe in the same letter told Catherine Bury that:

you will think me a good traveller when I tell you that the whole of the Jura and the whole of the Alps save a little bit of the Mont Cenis for we were too late for the Simplon and the whole of the Apennines I traversed on the box of my caliche [i.e. a caleche, a light, small-wheeled carriage with four seats] I who had never mounted a coach in my life before, but I cannot describe the pleasure I had in thus floating, as it were, in solitude.12

Fanshawe wrote the letter to Bury from Rome, which was a popular destination for British tourists; it has been estimated that as many as 2,000 British people visited the city in 1818.13 Over the next couple of decades more and more intrepid middle-class women travelled in search of excitement, new experiences and self-fulfilment. Mostly they went with their husbands or brothers, who in many cases were also travelling abroad for the first time, but sometimes with other women or even alone. The liberation that travel, especially to Italy, may have given these women from the domestic obligations of the home has been the subject of recent scholarly attention, as has the distinctive nature of their reportage when they wrote about Italian society and its customs.14 Of course Italy also continued to attract men, including most famously John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron, and a host of other successful Romantic poets.

Funerary monument to the English merchant William Walton of Wakefield, who died in Genoa in July 1823

Staglieno cemetery, Genoa

Photo: Ross Balzaretti

Fig.1

Funerary monument to the English merchant William Walton of Wakefield, who died in Genoa in July 1823

Staglieno cemetery, Genoa

Photo: Ross Balzaretti

More common than expatriates, however, were travellers who visited the long-established sights of the Grand Tour: classical Roman antiquities and Renaissance and Baroque artworks. The Grand Tour, on which young, upper-class gentlemen completed their classical education, had reached its zenith in the late eighteenth century but continued to influence the way people travelled well into the nineteenth century. However, tastes changed and in the early nineteenth century it became fashionable for travellers to seek out the romantic natural world and late medieval art and history which had not been very popular before. Less highbrow activities included shopping and illicit sex (especially for men, more rarely for women). One important attraction was the supposedly mild climate, which was believed to be especially advantageous for consumptive patients. ‘Invalids’ who could travel did so and guidebooks catered for their needs, especially those written by Mariana Starke, who travelled across Italy in the late 1790s with an ailing relative herself (probably her consumptive mother).21 Someone who was tempted by most of these attractions was the young, single lawyer Henry Matthews, who published his Diary of an Invalid in 1820, aged thirty-one.22 Matthews was ill with tuberculosis, and travelled south to escape the worst effects of the British climate and to make a full recovery. He entered Italy by an unusual route, having travelled by boat from Lisbon to Leghorn in twelve days.23 Despite being violently seasick, as he passed Trafalgar on 20 October 1817 he ‘Sung Rule Britannia, with enthusiasm; as the most appropriate requiem to the memorial of the immortal Admiral [Nelson]’.24 His account on the whole is surprisingly light-hearted for a sick man. On arrival at Leghorn he was told that he had to spend ten days in quarantine, which prompted the remark ‘before we enjoy the delights of an Italian Paradise, we are to be subjected to a purgatory of purification’, a sly dig at Catholic belief as well as a joke about customs rules.25 His route in Italy went from Pisa and Florence to Rome, where he stayed for Christmas and the famous Carnival, which many other travellers also chose to experience. However, he was disappointed by it, noting that ‘It may be, however, that I find it dull, because I am dull myself, for the Italians seem to enjoy it vastly’.26 He then visited Naples, wrote a long account of Pompeii and was rather ill with pleurisy much of the time. Even so, as an enthusiastic tourist and against his surgeon’s advice he ‘climbed’ Vesuvius, or rather eight men carried him up to the crater in an armchair.27 Having survived, and even enjoyed the ordeal, he slowly made his way home via Rome, Florence, Venice, Milan, Switzerland and France.

Matthews followed a fairly typical tour, although he wrote about it less formally than many of his contemporaries. Although like the majority of British travellers he was drawn to Europe largely for its art and architecture, after 1815 new motivations came to the fore, including visiting sites of famous recent British victories, such as Trafalgar as noted by Matthews. However, the emblematic site of ‘British tourism’ during this period was Waterloo, the object of several books, notably Narrative of a Residence in Belgium, during the Campaign of 1815, and of a Visit to the Field of Waterloo ‘by an Englishwoman’, which came out anonymously in 1817. This was written by Charlotte Waldie (later Eaton) who had visited the battlefield with her siblings John and Jane. Her account created something of a sensation when it appeared, as it represented the first eye-witness account of the battlefield itself in all its gory detail. The Waldie sisters went on to write other travel books that dealt with Italy, with Waldie’s Rome in the Nineteenth Century (1820) becoming the standard work. Other sites with Napoleonic associations were visited, including the Fort de Bard in the Aosta Valley, Marengo in northern Italy where Bonaparte defeated the Austrians on 14 June 1800, and the island of Elba itself, to which Napoleon had been exiled in 1814.28 Turner drew a scene of the battle of Marengo to illustrate ‘The Descent’, one of the poems in Samuel Rogers’s Italy, originally issued in 1822 but republished with twenty-five plates by Turner in 1830, which secured both its sales and its fame.29 Rogers’s poem, printed in a pocket-sized volume, drew on his own tour undertaken between August 1814 and May 1815 and was obviously a text that Turner knew, as did many other travellers at this time. The verses responded to fashionable themes including Alpine scenery, medieval history and banditti (‘bandits’). Like so many other travellers, Rogers had kept a detailed diary from which it is possible to trace his travels and his reactions to what he saw and those he met.30 For example, on Sunday 19 February 1814 he was conversing with the king of Naples ‘of Bonaparte and Elba’, but on 6 March 1815, still in Naples, he noted ‘Bonaparte gone from Elba’.31 His poem included reflections in prose on ‘Foreign Travel’ that expressed, alongside the conventional opinion that ‘ours is a nation of travellers’, the more original view that ‘travel restores to us in a great degree what we have lost’.32 Rogers, well known for his interest in memory, suggested in his popular poem ‘The Pleasures of Memory’ that through travelling we feel like children again, soon forgetting our pains but remembering forever our pleasures, especially those experienced while abroad.33 This sense of nostalgia was to become a prominent theme in travel writing during the later nineteenth century.

After 1830 the illustrated version of Rogers’s Italy became a popular gift for the departing traveller and secured the poet’s contemporary fame. A cheap pirated edition, clearly intended for the passing traveller, was printed in Paris in 1840, illustrated with naïve ‘cuts’ rather than Turner’s views.34 But the fame of Rogers was nothing, of course, by comparison with that of his friend Lord Byron, admirer of Bonaparte and the sensational celebrity of the day in whose ‘heroic’ footsteps so many travellers self-consciously followed. Byron was in Italy between 1816 and 1823, mainly in Venice, Ravenna and Genoa.35 ‘Celebrity spotting’ had long been an occupation for some travellers, with Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Rousseau, Madame de Staël and especially Voltaire being among those sought after. The places they had lived or visited became tourist sites. Such was Byron’s notoriety that some travellers pursued him with the deliberate intent of achieving a personal encounter. Lady Blessington succeeded and produced her renowned Conversations with Lord Byron in 1834 as a result, a book that helped to cement Byron’s reputation as the ultimate Romantic hero.36 She first met Byron in Genoa, where he was then living, on 1 April 1823 and her intimate portrait was initially published in instalments in the New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal between July 1832 and December 1833 (Byron having died in April 1824).37 This book reinforced Byron’s already strong connection with Italy, the subject of many of his poems and plays. Byron’s Childe Harold (Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto IV, was completed in 1818) became the most famous of his ‘Italian’ poems, and quotations from it appeared in many guidebooks for a century after it was first printed. Guidebooks not only contained practical advice about what to visit where, how to get there and which inn to stay in, but also inspirational verse (usually Byron’s) and images (sometimes Turner’s), which helped the novice tourist know how to react and feel. Travellers reading his poetry while on the move could explore Italy through Byron’s eyes. More mundanely they could also visit Byron’s foreign homes, notably his house overlooking Lake Lausanne in Switzerland and the Palazzo Mocenigo on the Grand Canal in Venice.

The ever-increasing number of travel books about Italy coupled with poems and plays set in Italy, both past and present, helped to entice a greater range of people to travel there from Britain. The scale of travelling itself soon became a subject of controversy, at least in some circles as a sort of anti-tourist snobbery set in. Byron famously commented that Italy was peopled by ‘staring boobies, who go about gaping and wishing to be at once cheap and magnificent. A man is a fool who travels now in France or Italy, till this tribe of wretches is swept home again. In two or three years the first rush will be over, and the Continent will be roomy and agreeable’.38 While this is an extreme example of contemporary opinion, it does chime with criticism in the British press that too many were lured by foreign travel and that women in particular should stay at home in the warm embrace of domestic life. This could spill over into real unpleasantness, as that voiced by several conservative reviewers of Lady Morgan’s Italy (1821), a book that appeared while Parry and Fanshawe were on the road and was castigated for its radical politics and for being too sympathetic towards papist Italians.39 Byron, by contrast, thought it a ‘really excellent book’.40 The controversy surrounding Morgan’s Italy, which was one of the most detailed and intelligent portraits of the country and its inhabitants that had yet appeared in English, placed it in a different category from the run-of-the-mill travel narratives intended to profit from the revived post-war interest in continental travel. Such books appeared in considerable numbers between 1814 and 1830.41 A similar outpouring of unpublished accounts (diaries, journals and other forms of reminiscence) can be found in many archives for the same period, and have provided much of the evidence for this essay.42

Appearing alongside serious guides and memoirs were various satirical works that mocked the new breed of English travellers, notably The Fudge Family in Paris, published by the Irish poet Thomas Moore in 1818, which poked fun at English and Irish travellers in France immediately after the Napoleonic Wars had ended.43 Moore, a friend of Byron and Lady Blessington, abandoned the projected ‘Fudge Family in Italy’ but did publish The Fudge Family in London in 1835.

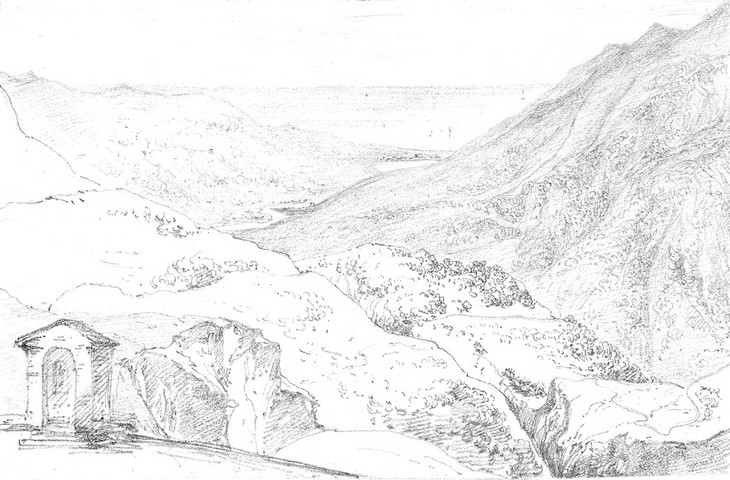

James Hakewill

From the top of the Bocchetta looking towards Genoa 1816

British School at Rome Library

Fig.2

James Hakewill

From the top of the Bocchetta looking towards Genoa 1816

British School at Rome Library

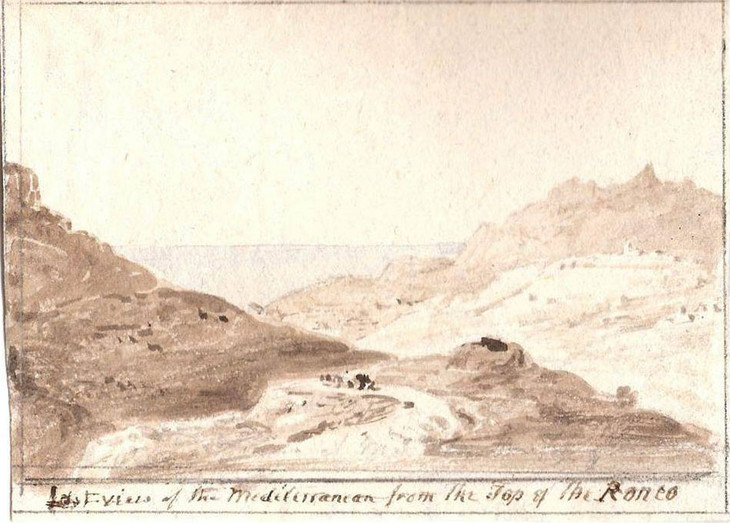

Elizabeth Christiana Fanshawe

Last (1st) view of the Mediterranean from the top of the Ronco c.1829

Private collection

Fig.3

Elizabeth Christiana Fanshawe

Last (1st) view of the Mediterranean from the top of the Ronco c.1829

Private collection

The tension between individual and group experience is evident in the published and unpublished archival material. People who went to Italy in search of themselves did so in such numbers that they could not escape other travellers. The ‘first view of the Mediterranean Genoese’ as reported by both Harriet Parry and Catherine Maria Fanshawe is typical. They presented their experiences as unique, whereas by 1820 the view had already become a classic, even hackneyed scene for professional artists. This exact view had been sketched by John Robert Cozens in 1776. It was sketched again in 1816 by James Hakewill, and reproduced as an engraving in his Picturesque Tour published in 1820 by John Murray, a publication that incorporated some of Turner’s images too (fig.2).44 The book sold well as it capitalised on the renewed desire for continental travelling in those immediately post-Napoleonic years.45 Elizabeth Christiana Fanshawe produced a further version of this view on her travels in the region in 1829–30 (fig.3).

Travellers were able to access the Bocchetta Pass relatively easily by road. However, by 1829, when the Fanshawe sisters were travelling in the region, a much easier way from Novi to Genoa existed on a new road at much lower altitude. This is clear from several accounts and from local archival documentation. Robert Wilkinson, travelling in the area in early September 1823, wrote in his diary: ‘proceeded from there [Novi] to Arconate [Arquata Scrivia?] along a very rough road. From Arconate we proceeded to Roncho [Ronco Scrivia] by a very made road, in many places on walls built up to support it. From Roncho to Ponte Decimo was the next stage. Over a hill where is a fine Road winding and very much like the Simplon.’46 The Fanshawe sisters appear to have intentionally put themselves at greater risk specifically to see this famed prospect. By 1840 though the old road was clearly seen as ‘dangerous’, and travellers were authoritatively told to take the ‘fine new road’.47

Getting there

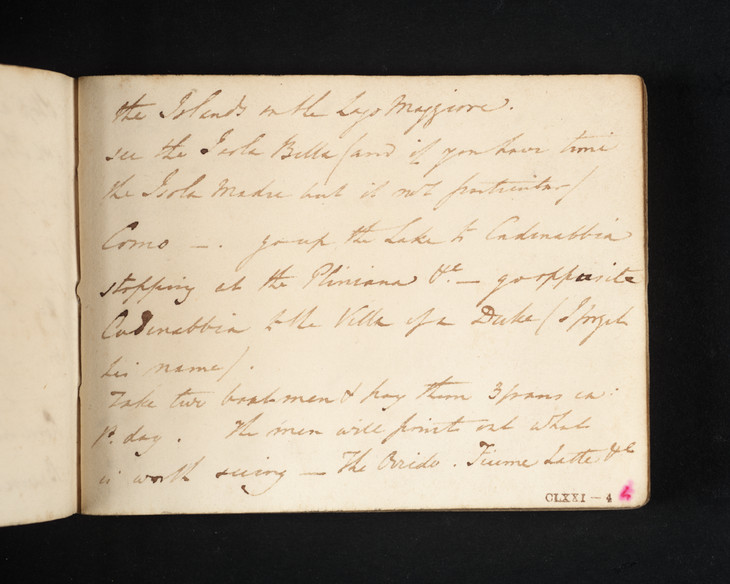

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Notes by James Hakewill on Travelling in Italy 1819

Pen and ink on paper

support: 88 x 114 mm

Tate D13865

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.4

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Notes by James Hakewill on Travelling in Italy 1819

Tate D13865

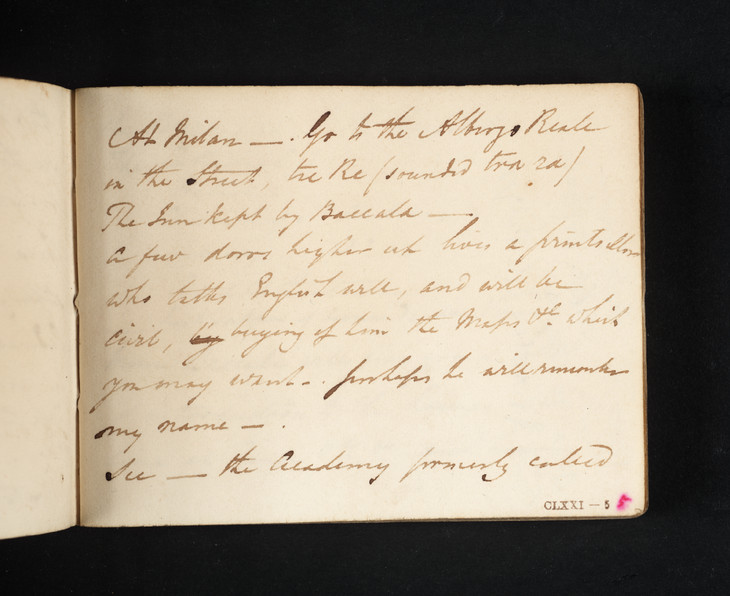

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Notes by James Hakewill on Travelling in Italy 1819

Pen and ink on paper

support: 88 x 114 mm

Tate D13867

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.5

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Notes by James Hakewill on Travelling in Italy 1819

Tate D13867

As has been demonstrated, Turner was among hundreds of people who travelled to Italy after wartime restrictions had been lifted in 1815.48 Like all travellers at this time he was concerned with the practical aspects of getting around.49 His sketchbooks contain advice from James Hakewill on where to go and where to stay, and he made notes himself about possible routes (figs.4–5).

By 1819 some travellers were deliberately seeking out places off the beaten track, as we have seen with the Fanshawe sisters in the Scrivia Valley. Most, however, stuck to established routes, such as the member of the Mellish family from Blyth in north Nottinghamshire who made a series of notes for possible places to visit in Italy, which included Piacenza, Parma, Modena, Bologna, Foligno, Spoleto, Terni, Narni, Otricoli and Civita Castellana, as well as the more obvious Rome, Milan, Verona, Venice and Padua.50 Although this list may look quite adventurous, these were all well-established stopping places. The standard routes for getting between the great cities were listed in detail in guides and road-books of which the sixth edition of Mariana Starke’s Information and Directions for Travellers on the Continent (‘Thoroughly revised and corrected with considerable additions, made during a recent expensive journey undertaken by the author, with a view to render this work as perfect as possible’ according to the title page) may serve as typical.51 Arriving in Italy by the road route over the Simplon Pass, the traveller was advised to proceed by carriage via Domodossola and the ‘gloomy hamlet’ of Gondo to Baveno via Lake Maggiore, which was visited for its famed Borromean Islands. From there a boat was taken to Sesto Calende, where they joined a military road all the way to Milan.52 The north Italian lakes became increasingly fashionable as visitors to the English Lake District encouraged an appetite for lake landscapes. In 1815 the archaeologist Sir Richard Colt Hoare declared of Lakes Como and Maggiore that ‘this delightful tract of country is known to me only by report; but report speaks so loudly, and so universally in its favour, that I feel no reluctance in recommending it to my countrymen’.53 By 1828 Starke was recommending the lakes as part of a standard tour. Developing interest in medieval and early Renaissance art and history and the search for romantic landscapes encouraged some travellers to go inland to places once rarely visited, such as Orvieto, Assisi, Arezzo and Perugia where early art could be found in medieval churches.

Archives contain other eminently practical documents, none more so than the passport that was necessary in order to get across the Channel and thereafter, both to cross into Italy and move from one state to another within the peninsula. Unlike modern passports, early nineteenth-century ones were large pieces of paper, and provided detailed descriptions of faces and other distinguishing marks.54 Henry Matthews explained how ‘At the gate of Pisa, I first encountered the restraints of continental travelling, in the examinations of my passport and baggage’.55 His annoyance is barely concealed. Several surviving examples of passports in the University of Nottingham archives give a good idea of the kind of passport Matthews would have carried, of which that issued by George Canning to Mrs Ann Chambers on 26 March 1827 is typical.56 This allowed her, her family members and servants to travel in France and Germany, and indeed they went to Calais, Strasbourg and Dresden among other places. These are useful sources with which to determine the size of travelling parties, which were often quite small. On 19 September 1845 the fourth duke of Newcastle, Henry Pelham-Clinton, one of England’s grandest aristocrats, travelled to Paris with his four daughters, one chambermaid, one domestic and a courier.57 Occasionally servants are named, as with the Monsieur Crotch and Monsieur Mattieu who accompanied an earlier duke of Newcastle and his wife across the Channel in 1816.58

Turner, like most other travellers in this period, used a guidebook (rather than a man as a guide as was customary in earlier centuries).59 Several were available in 1819, and many more by 1828. He most probably used one published by the Galignani family in Paris, a specialist travel publisher.60 There were various types of guide ranging from the relatively simple ‘road-book’ to the more complex and detailed works published by Mariana Starke. The most basic practicalities of travel within Italy at this time are well documented by contemporary road-books, structured as they were around ‘posts’ and daily stopping places.61 These were a simple type of guide that focused on how to get from one place to the next and kept narrative about what to see and how to react to it to a minimum. During Turner’s lifetime such books were issued and reissued regularly to keep travellers up to date with the latest developments, such as new improved roads, and, from the 1840s, the slowly emerging Italian rail network.

A popular work was William Brockedon’s Road-Book from London to Naples published by John Murray in 1835 with twenty-five illustrations (by Clarkson Stanfield, Samuel Prout and Brockedon himself). This began with a chapter of practical advice of the sort needed by most travellers (passports, money, conveyances, luggage), unless they could afford to employ others to do those things for them. The form of the rest was fixed around ‘routes’, the roads divided into sections between posts with the distances and costs explained. This made the book eminently functional but, by virtue of the plates and accompanying narratives, instructive (and occasionally hectoring). Due to successive improvements to roads and places to stay made by Napoleon, the Piedmontese and the Swiss, Brockedon was able to suggest that ‘a journey to Naples is now as easy an accomplishment as a tour of England’, which seems unlikely.62 The audience for this work seems clearly to be middle-class rather than aristocratic or genteel as readers were clearly expected to arrange things for themselves: going to the relevant passport office in good time, organising Herries and Co.’s bills of exchange (a form of travellers’ cheque), ordering a carriage well in advance or roughing it by diligence or malle poste (mail coach), and restricting luggage to essentials and refraining from taking too many clothes.63 Servants posed another potential problem, especially English female ones who were deemed ‘generally useless’ when compared with their French counterparts.64 He ended with a warning – directed at ‘vulgar and half-witted Englishmen’ – against the idea that money can buy anything while abroad. Civility and forbearance were much more useful than hard cash.

Hot on the heels of Brockedon was Captain Jousiffe’s Road-Book for Travellers in Italy, first issued in 1839. Jousiffe, an army man, was the author of several other road-books. In the second edition of the Italian one, Jousiffe, perhaps with some irony, stated that he would ‘avoid the errors so frequently found in the Guide-Books of the present day, most of which are notoriously copies of old works which are more calculated to lead the traveller astray than afford him the required information’.65 Unfortunately, the first edition had been full of exactly such errors, for which an apology was made: ‘the work was published in his absence’ and he had not seen the proofs. All copies of the 1839 edition appear to have been destroyed suggesting that publishers by this time took the accuracy of the information printed very seriously. Like Brockedon, Jousiffe was at pains to stress how much was new: roads, hotels and ‘interesting objects discovered’. He also emphasised the number of English residents in Italy whom the sensible traveller would meet and employ in preference to Italians given the chance (the opposite advice given by Brockedon). Throughout the remainder of his text, Jousiffe commented on the quality of hotels and inns at some length, often noting their inadequacies and making it clear that this was his own opinion by attributing comments to ‘(Author)’. At Borghetto Vara, for instance, ‘the only house of reception is miserably dirty, exorbitantly dear, and the master and servants are very insolent’.66 His descriptions of sights were, by contrast, brief and bland suggesting a very different – less cultured – market from Brockedon’s more sophisticated volume.

There was considerable overlap in form and intention between road-books and guidebooks, both of which had eighteenth-century origins. The most famous Victorian series of guides – Baedeker, Cook and Augustus Hare – came into being just after Turner’s death in 1851. These drew on existing examples, above all those of John Murray III, whose first Italian guide was printed in 1842.67 Although he is often credited with creating the first guidebook, in fact he did no such thing. He drew substantially on the precedent of Mariana Starke (active in the early 1800s and published by John Murray II), Henry Coxe (pseudonym of John Millard), Richard Colt Hoare, Galignani (the Paris publishing firm) and some others. These books all adopted similar formats and contained similar information, often directly copied (without acknowledgment) from each other. A typical example is Galignani’s Traveller’s Guide through Italy, published in Paris in 1824. A lengthy volume of 666 pages with a thorough index, it began with sections on the geography, climate and history of Italy. A schematic ‘Plan of a Tour in Italy’ followed.68 This was complemented with advice on travel itself, including how to hire a coach or how to use public transport; it is notable that the railway network had barely developed in Italy before its unification in the 1860s.69 An explanation of the complex currency of the Italian states completed this introductory material. The rest of the work was in the form of detailed guidance for specific routes and places. For example, how to get from Antibes to Genoa was detailed over five pages.70 Other possible routes to Genoa were presented. Once at Genoa, the guide expanded upon the local sites and things ‘worth seeing’.71 Readers were told that ‘The best Inn at Genoa is the Hotel di Londra. It is situated not far from the landing place’.72 The prices were fair and the food ‘well dressed in the English, French and Italian manner’. The description of the city emphasised the beauty of its ‘picturesque’ situation, its palaces ‘literally heaped upon one another in the streets’, the churches, the port and its charitable institutions. The local natural history was highlighted as particularly attractive for ‘herborizing excursions’.73 The local food and climate received by contrast a mixed press.

The volume has similar entries for most of the major Italian cities and many smaller towns. The text was informative but not very critical and other guides, notably Mariana Starke’s, often included much more detailed information about galleries and the pictures and sculptures that they contained. In her Information and Directions for Travellers on the Continent (1828), the section on Genoa covers much the same ground as Galignani but is much more detailed with long lists of pictures to be seen accompanied by her novel ‘starring’ system (indicating particularly worthwhile sights by one, two or three exclamation marks).74 Her list of Genoese hotels included Galignani’s Hotel de Londres, but also four alternatives: the Hotel de York (‘excellent’), Hotel de la Ville (‘dear’), the Croce di Malta (‘reasonable but best for single men not families’) and the Hotel de la Poste (‘cheap’).75 It is worth adding that travellers could also purchase local guides when they arrived in a place, such as the Italian Piccola Guida di Genova published in 1846, which covered much the same ground as Galignani and Starke but came with a city plan too.76 Some travellers, especially women, had learnt Italian at home and specialist phrasebooks were beginning to appear in the 1840s as a new genre for the travelling public.77

Starke’s numerous guides seem to have been intended for solidly upper-middle class travellers like her with time to devote to travel, or perhaps for those travelling with an invalid in search of health as she did. Her publisher was John Murray (both II and III), who published most of the guides and effectively cornered this burgeoning market in the first half of the nineteenth century even before he started issuing his own volumes.78 As is well known, much snobbery surrounded such works that were thought by some to characterise a debased sort of middle-class travel. Many travellers therefore sought to distance themselves from his guides, perhaps as a way of fashioning themselves as ‘real’ independent serious travellers. Mary Wilson in her diary entry for 10 June 1847 noted, while in Milan, that ‘We then walked through a very pretty public garden to the Lazaretto, which was used at the time of the plague, but has been since allowed to go to ruin & is now let out in beggarly little shops, we should not have gone to see it but for that misleading book of Murray’s, which is complete rubbish’.79 They were probably using the first edition of the work, as the Lazaretto is not mentioned in the second of 1847 (in which ‘many omissions were made’). Marianne Wilkinson, who travelled from 1844 to 1845, quite frequently referred to Murray in disparaging terms. In Rome, on 15 November 1844, she gloried ‘in having seen St Peters without Murray. It was quite a relief to be in happy ignorance, instructed only by my own eyes and ears, with such general recollections as come naturally, enhancing the charm of everything in this interesting city’.80 She clearly referred to it often though, given the number of other references she made to it: already it was a necessary companion to continental travel whether valued or disparaged. The book she mostly used was the Hand-Book for Travellers in Northern Italy, the first edition of which was published in 1842 and was largely written by the historian Sir Francis Palgrave (but none of the revised editions were).81

Hazards of Travel

The publication of more and more guides encouraged new travellers, and overcrowding was a common complaint in diaries and journals, as was the terrible state of beds, furnishings, food and just about anything else that could be complained about. On his arrival in Genoa on 9 July 1840 en route from Rome for Turin, Lord William Pelham-Clinton (fourth son of Henry Pelham-Clinton, the fourth duke of Newcastle) recorded: ‘I arrived here at half past four this morning, it was not however til 3 hours after that I got finally on shore, and finding all other hotels full I am now at the Hotel Royal.’82 In late October 1825 Mrs Elizabeth Mellish confided to her journal that at her ‘noisy, dirty, lofty, stinking Hotel’ in Genoa ‘we had neither cream nor butter for breakfast; we knew that our fare later in the day would consist of variety – but of a variety in which blackness and oiliness never failed; we were often treated with a bit of dried looking veal for “beeksteak” and when we asked for la mode Italienne au lieu du la mode Angloise, we were worse off, and they don’t know how to dress Maccaroni, at least they did not at Genoa’.83 Although she bemoaned the heat and mosquitoes in Genoa, just a week later she complained of the cold in Florence, where she would have put on her furs like the locals had she brought them with her.

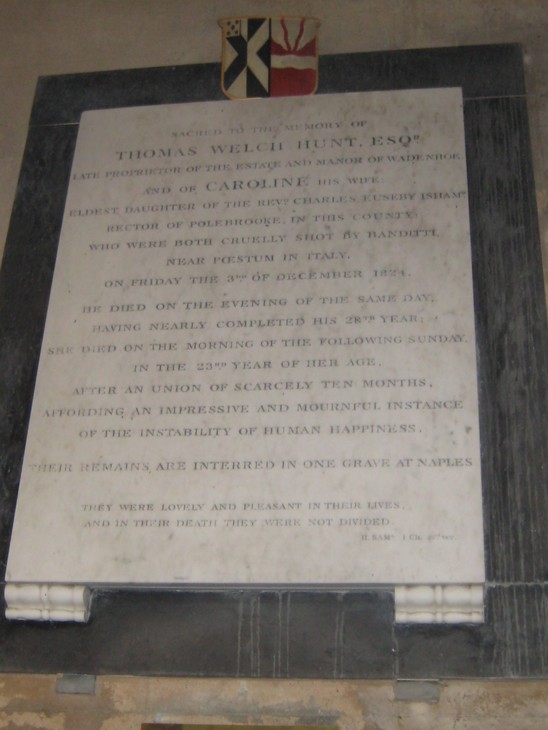

Memorial to Caroline and Thomas Welch Hunt, St Giles's Church, Wadenhoe, Northamptonshire 1824

Fig.6

Memorial to Caroline and Thomas Welch Hunt, St Giles's Church, Wadenhoe, Northamptonshire 1824

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Banditti, for Rogers's 'Italy' c.1826–7

Pen and ink, graphite and watercolour on paper

support: 247 x 301 mm

Tate D27681

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.7

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Banditti, for Rogers's 'Italy' c.1826–7

Tate D27681

Travellers sometimes also clashed with the locals, especially servants travelling with their employers.91 A good example is Matthew Todd who travelled with Captain Andrew Barlow in 1814–15, when twenty-three years old. They got into many scrapes and, as advised, kept pistols at the ready to defend themselves. As they travelled by ship from Genoa to Civitavecchia, Todd got into a fight with the captain’s mate when he asked them at Portofino to give up their beds on board and go ashore to sleep. As Portofino was ‘an outlandish place’, Todd refused: ‘At the same time he took our baggage forcibly and pushed it towards the cabin door. This I could not stand, and insisted upon his not further moving the baggage ... some stormy arguments took place between us.’92 He was in trouble again in early February at Leghorn. They were dining with some English sailors when,

One of the party, a little consequential midshipman, being pot valiant [drunk], thought to insult me, by calling me a landlubber and other insulting expressions. However, I did not choose to sit down with it, and told him, Landlubber as I was, I thought myself a match for a Salt-water sprat like him, and would meet him in any way he chose to name.93

Pistols were drawn but it all blew over as the midshipman was quickly arrested.

Another life-threatening problem often encountered by travellers in most parts of Italy was flooding, which then as now could be severe. As has already been noted, Harriet Parry noticed that the riverbeds her carriage passed through were dry in July 1819. However, summers were not always so safe, as Mary and Agnes Berry – the famous bluestocking friends of Horace Walpole – found on Thursday 12 June 1823 on their way from Rome back to Genoa. The River Magra was in flood: ‘the peasants said we could pass ... with the help of a horse to our three mules and ... peasant guides’.94 Mary reflected: ‘One crosses that horrid river five times before reaching Borghetto; but the other fords were wider, and less water.’ Had Parry and the Berrys travelled in the autumn it could have been worse as, in Liguria, there is evidence that floods made travelling impossible, especially in October and November. A remarkable case in point is the story regaled in The Landscape Annual for 1833.95 The brief chapter on ‘La Spezzia’ is largely taken up with the borrowed account of a near-fatal encounter with the River Magra, which the doctor James Johnson had first set out in Change of Air, or the Diary of a Philosopher in Pursuit of Health and Recreation (1831). The incident is worth quoting in full:

Another life-threatening problem often encountered by travellers in most parts of Italy was flooding, which then as now could be severe. As has already been noted, Harriet Parry noticed that the riverbeds her carriage passed through were dry in July 1819. However, summers were not always so safe, as Mary and Agnes Berry – the famous bluestocking friends of Horace Walpole – found on Thursday 12 June 1823 on their way from Rome back to Genoa. The River Magra was in flood: ‘the peasants said we could pass ... with the help of a horse to our three mules and ... peasant guides’.94 Mary reflected: ‘One crosses that horrid river five times before reaching Borghetto; but the other fords were wider, and less water.’ Had Parry and the Berrys travelled in the autumn it could have been worse as, in Liguria, there is evidence that floods made travelling impossible, especially in October and November. A remarkable case in point is the story regaled in The Landscape Annual for 1833.95 The brief chapter on ‘La Spezzia’ is largely taken up with the borrowed account of a near-fatal encounter with the River Magra, which the doctor James Johnson had first set out in Change of Air, or the Diary of a Philosopher in Pursuit of Health and Recreation (1831). The incident is worth quoting in full:

On approaching Borghetto, situated in a wild and savage-looking country, we encountered one of those mountain torrents so common in Italy, and which was foaming down a steep course, and falling into the Magra within a hundred yards of the place we were to cross. The torrent had evidently been momentarily swelled by some rain that fell among the mountains in the night, and, though narrow, appeared to me to be rather dangerous. GALLIARDI was of a different opinion, and drove boldly into the stream. By the time we reached the deepest part of the bed, the water began to curl into the carricello, and the BUONA BESTIA was unequivocally tottering, and even lifted occasionally off the bottom. I saw at once that we were in imminent peril, and instantly threw off my cloak to swim for it. At this moment Galliardi sprang from the shaft into the torrent, and, floundering like a grampus, reached the farther bank in a twinkling, leaving me and the mule to shift for ourselves! Seeing the MAGRA roaring along within a few yards on our right, and not wishing to leave my bones in that river at this time, I was on point of following Galliardi’s example, when he bawled out to me to keep my seat. I should have paid very little deference to this advice, being conscious that I could swim tolerably well, but at this critical moment, the poor animal, lightened of half its load, and apparently encouraged by the sight of its master on dry land, made two or three convulsive plunges, and obtained firm footing on the shelving bank, where Galliardi vigorously assisted him in dragging the carricello and myself out of the water! I confess that this little aquatic excursion gave me no great relish for the new road, although Galliardi assured me I should become quite reconciled to such incidents, especially between Genoa and Nice.96

The situation appears not to have improved by 1840 when Captain Jousiffe remarked that ‘After leaving Sarzana the river Magra is crossed by a pont-volant [a temporary wooden structure]. If it were possible to erect a bridge here, it would add much to the safety as well as convenience of the traveller, as the passage of this river is often very dangerous, from the violence of its torrent’.97 Johnson’s Change of Air, lengthier and much more literary than Jousiffe’s commentary, is a minefield of fascinating information about the hazards, real and perceived, that travellers faced and indeed sometimes sought out and enjoyed. Once Johnson, Galliardi and the ‘BUONA BESTIA’ had crossed their torrent they ascended one of Italy’s ‘sites of terror’, the Bracco Pass. As in some Gothic novels, a genre still popular at this time, Johnson’s account is peppered with adjectives to reinforce the horror awaiting them: ‘the TERRIFIC’, ‘horrifying’, ‘wild and savage beyond description, or even imagination’, ‘lonely’, ‘sublime’, ‘gloomy horrors’ contrasting with ‘pleasant sensations’.98 All this in a single paragraph.

One of the biggest problems faced by many on arrival in Italy was not related to the natural world but to humans: how to deal with the local people. Relatively few employed Italian servants like Johnson and most were capable of the unpleasant anti-Italian sentiments regularly expressed by all classes of English visitor. An example of the more extreme sort of opinion is that expressed by Jane Waldie, in her anonymously published Sketches Descriptive of Italy in the Years 1816 and 1817 (1820). Waldie travelled with her elder brother John and sister Charlotte, author of Rome in the Nineteenth Century, also dated 1820. The final chapter of Jane’s four-volume work dealt with the ‘Character of the Italians’ and contains such jaundiced comments as: ‘Totally to divest the mind of every latent prejudice, is neither attainable nor desirable. Happy we with whom reason confirms that sentiments cherished by patriotism. If I am unfavourable to the Italians, it is because my ideas of national character are rated by a standard far above their; – for I entered Italy, unprejudiced – at least against them.’99 She railed against Italian beggars while pointing out the extent of British charitable activities towards them: ‘into whatever land the British find their way, they seek to alleviate the sufferings around them.’ Italians, by contrast, still live, ‘as they have ever lived, contented slaves’, a rather pointed remark given contemporary debates about slavery in Britain. Waldie, unlike many travellers, knew the Italian language well and lived in the country for some time. As a talented painter she also enjoyed the landscape. Almost all works about travel in this period refer to Italian ‘dirt’, untrustworthiness, thieving, insolence, superstitious religious beliefs and practices, and so on. It is worth noting that such attitudes were taught early on in children’s books, such as those published and written by Peter Parley. At the end of his Tales about Rome and Italy the child reader was advised that,

We must now bid farewell to the Eternal City! Farewell to the beautiful lands, which are covered in such magnificent monuments of art, and blessed with such profuse bounties of nature! We will go back to the humble and unpretending home of our own country, and to the stubborn soil, which yields its harvest only to the hand of laborious industry. We will return, without a sig for the splendor we have left; because we return to happy firesides, and to a virtuous people.100

These attitudes were reinforced by the guidebooks on which many adult travellers increasingly came to rely, although some, notably those of Mariana Starke, who lived for some seven years in the country and whose guides are generally very level-headed, voiced more positive sentiments. Her remarks on Florentines are typical: ‘they are, generally speaking, mild, good-humoured, warm-hearted and friendly’, attributes which were ‘endearing to Foreigners’.101 The career of Mariana Starke provides an interesting example on which to end. Fourteen years older than Turner, she carved out a special niche as the author of reliable guidebooks. She began with Letters from Italy, between the years 1792 and 1798 containing a view of the Revolutions in that country (1800) and proceeded via Travels in Italy, Between the Years 1792 and 1798 (1802), Travels on the Continent (1820), Information and Directions for Travellers on the Continent (1824; expanded and republished as Travels in Europe for the use of Travellers on the Continent and likewise in the Island of Sicily, to which is added an account of the Remains of Ancient Italy in 1832), Travels in Europe Between the Years 1824 and 1828 (1828), to Travels in Europe (1839), published after her death by the Galignani brothers.

Starke died in Milan aged seventy-six in the spring of 1838. Her will, proved on 11 September 1838, is very revealing of her personal interests and Italian connections. In addition to bequests of property and cash to various friends and servants, she left paintings by Salvator Rosa and Etruscan pottery to a nephew and another ‘small oval cabinet picture painted on copper by Salvator Rosa and enclosed in an ancient frame together with my two alabaster statues by Bartolini’ to a woman friend. Sums of cash went to Mrs Jane Gort ‘for the expense of her journey to England when she quits my service in Italy’ and to ‘my faithful servant Saverio Garguilo a native of the Piano di Sorrento’.102 These phrases provide tantalising evidence of her life spent living in and writing about Italy. This became possible for women only during Turner’s lifetime, and it is no coincidence that much evidence cited in this essay comes from the pens of women. They clearly found travel liberating, whether they travelled briefly (like Harriet Parry), repeatedly (like Catherine Maria Fanshawe and her sisters) or throughout a lifetime (like Mariana Starke). For all those that travelled there were, of course, very many more who did not, but they could stand in front of Turner’s pictures on display in London or glance at them in engraved form in books in their homes, and they too could dream like Fanshawe of ‘this vast country of the illustrious Dead’.

The first few decades of the nineteenth century saw many more people travelling outside Britain. For the middle-class majority tours were no longer ‘grand’ but short and concentrated on highlights alone. Unsurprisingly a more elaborate tourist infrastructure developed in response to these changing social and cultural patterns. In Italy, as elsewhere, this meant more and better roads, safer and faster carriages, smarter and more comfortable hotels, which were all described at length by the numerous guidebooks published in this period. These became more and more elaborate. Mariana Starke was particularly concerned to present the most up-to-date information in successive editions of her various guides. When she died in 1838, this role was taken up by her publishers John Murray whose first Handbook for Northern Italy appeared in 1842. Guides were increasingly pocket-sized, detailed and up to date. It did not take long before travellers became fed up with such prescriptive texts, as has been noted in the cases of Mary Wilson and Marianne Wilkinson travelling in the mid-1840s. By then they often wanted to travel to escape Britain’s increasingly smoky and crowded industrial cities for their health as well as to see the world, in tune with the spirit of adventure prevalent in mid-Victorian Britain.

Speen is a suburb of Newbury, two kilometres or so north-east of the centre of Newbury. Speen Hill is now the site of modern housing.

Harriet Parry, ‘Tour in France, Switzerland and Italy’, British Library, London, Add. 62945 A and B.

Turner produced an image of the Simplon ‘gallery’ (i.e. Pass): Tate T04743, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-the-simplon-t04743/text-catalogue-entry , accessed 1 July 2015.

Pietro Piana, ‘Topographical Art and Landscape History in Central-Eastern Liguria (c.1770–1840)’, unpublished Ph.D thesis, University of Nottingham 2015; for a later period, see Ross Balzaretti, ‘Victorian Travellers, Apennine Landscapes and the Development of Cultural Heritage in Eastern Liguria, c.1875–1914’, History, no.96, 2011, pp.436–58.

Catherine Maria Fanshawe, letter to Catherine Maria Bury, 11 January 1820, University of Nottingham, Marlay Papers, My 269, transcribed by Ross Balzaretti and Charles Watkins. Fanshawe implies here that her sisters were better at drawing landscapes than she was. We are grateful to Mark Dorrington, Keeper of Manuscripts, for permission to quote from this letter.

As evidenced in the posthumously published collection edited by William Harness, The Literary Remains of Catherine Maria Fanshawe, privately printed 1865.

Ross Balzaretti, Pietro Piana, Diego Moreno and Charles Watkins, ‘Topographical Art and Landscape History: Elizabeth Fanshawe (1779–1856) in Early Nineteenth-Century Liguria’, Landscape History, no.33, 2012, pp.65–81.

J.R. Hale (ed.), The Italian Journal of Samuel Rogers, London 1956, pp.56–99 remains an excellent account of English travel on the continent at this time.

Catherine Maria Fanshawe, letter to Catherine Maria Bury, 11 January 1820, University of Nottingham, Marlay Papers, My 269.

Alison Chapman and Jane Stabler (eds.), Unfolding the South: Nineteenth-Century British Women Writers and Artists in Italy, Manchester 2003; Jane Stabler, ‘Taking Liberties: The Italian Picturesque in Women’s Travel Writing’, European Romantic Review, no.13, 2002, pp.11–22; Jane Stabler, ‘“Know me what I paint”: Women poets and the aesthetics of the sketch 1770–1830’, Studies in Literature, no.39, 2007, pp.23–34.

For instance, Galignani’s Traveller’s Guide through Italy, Paris 1824, pp.xviii–xx: ‘A prudent person, not ambitious of passing for an Englishman of fashion, may certainly live very reasonably in Italy’ (p.xviii, emphasis in original).

Edith Clay, Lady Blessington at Naples, London 1979; Ross Balzaretti, ‘British Women Travellers and Italian Marriages, c.1789–1844’, in Valeria Babini, Chiara Beccalossi and Lucy Riall (eds.), Italian Sexualities Uncovered: The Long Nineteenth Century (1879–1914), Basingstoke 2015, pp.264–5.

Charles Dickens (ed.), The Life of Charles James Mathews, Chiefly Autobiographical, London 1879, vol.1, p.156.

See the ongoing research project ‘Leghorn Merchant Networks’: https://leghornmerchants.wordpress.com/home/leghorn-merchants/ , accessed 1 July 2015.

For Florence, see http://www.florin.ms/cemetery.html , which lists all the graves with much useful additional information, accessed 1 July 2015; for Livorno, see Matteo Giunti and Giacomo Lorenzini (eds.), Un archivio di pietra: l’antico cimitero degli inglesi di Livorno. Note storiche e progetti di restauro, Pisa 2013.

The authors visited Staglieno on 29 April 2014. The British section of this vast burial ground is rather overgrown but contains many early nineteenth-century graves. Staglieno was much favoured by British tourists later in the nineteenth century.

John Ingamells, A Dictionary of British and Irish Travellers in Italy 1701–1800, New Haven and London 1997, p.891.

Henry Matthews, Diary of an Invalid; being the journal of a tour in pursuit of health; in Portugal, Italy, Switzerland, and France, in the years 1817, 1818, and 1819, London 1820. All citations are to the modern reprint issued by Nonesuch in 2005.

A sea voyage may have been recommended for his tuberculosis: there was much debate about how to treat this disease in the early nineteenth century, with some arguing that a ‘foreign climate’ was helpful, at least in the early stages of the disease. James Johnson, Change of Air or the Diary of a Philosopher in Pursuit of Health and Recreation, London 1831, pp.267–72, gave advice on pulmonary consumption, citing Matthews. Mariana Starke, Information and Directions for Travellers on the Continent, 6th edn, London 1828, p.2, advised consumptive travellers to take the boat from Marseilles to Leghorn as ‘best calculated to benefit’ them.

Matthews 1820, p.33. The Battle of Trafalgar had taken place on 21 October 1805, twelve years earlier.

This fort ‘gave occasion to one of the most brilliant displays of French valour, and Buonaparte’s generalship, on record’, Thomas Roscoe, The Landscape Annual for 1833, London 1833, p.266, with an engraving of a drawing of it by J.D. Harding opposite, p.265.

Turner’s original watercolour: Tate D27663, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner/joseph-mallord-william-turner-marengo-for-rogerss-italy-r1133297 , accessed 1 July 2015; the published steel engraving: Tate T04639, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-marengo-t04639 , accessed 1 July 2015. On the publication history of Rogers’s Italy, see Cecilia Powell, Italy in the Age of Turner: ‘The Garden of the World’, London 1998, pp.95–7. Rogers’s 1830 edition sold 10,000 copies.

In a letter to Thomas Moore, 25 March 1817: Peter Gunn (ed.), Byron: Selected Letters and Journals, Harmondsworth 1972, p.205.

Lady Morgan, Italy, London 1821, and Lady Morgan, Letter to the Reviewers of ‘Italy’; including an answer to a pamphlet entitled ‘Observations upon the calumnies and misrepresentations in Lady Morgan’s Italy’, Paris 1821.

Maria Schoina, Romantic ‘Anglo-Italians’: Configurations of Identity in Byron, the Shelleys, and the Pisan Circle, Farnham 2009, p.95.

Benjamin Colbert, ‘Bibliography of British Travel Writing, 1780–1840: the European Tour, 1814–18 (excluding Britain and Ireland)’, www.cardiff.ac.uk/encap/journals/corvey/articles/cc13_n01.html , accessed 1 July 2015; Pine-Coffin 1974, pp.162–87 on books published between 1814 and 1821.

Lorna Watson, The Errant Pen: Manuscript Journals of British Travellers to Italy, La Spezia 2000, pp.28–38.

The original drawing (James Hakewill, From the top of the Bocchetta looking towards Genoa July 1816) is reproduced in Tony Cubberley, Luke Herrmann and Valerie Scott, Twilight of the Grand Tour: A Catalogue of the Drawings by James Hakewill in the British School at Rome Library, Rome 1992, p.136.

There is, for example, a copy in the Bromley House Library in Nottingham, a private subscription collection opened in 1816. According to the librarian Carol Barstow, it is likely that the book was purchased on publication.

‘Journal of Robert Wilkinson 21 August–28 September 1823’, Birmingham University Archives, MS9/1, Sunday 7 September.

James Hamilton, Turner: A Life, London 1997, pp.195–204, and Cecilia Powell, Turner in the South: Rome, Naples, Florence, New Haven and London 1987, pp.20–35 and the map of his travels printed on the endpapers.

He made preparatory notes, for example, from Revd John Chetwode Eustace’s A Classical Tour through Italy, the standard work of the day, first published in 1813. Hamilton 1997, p.196.

University of Nottingham, Newcastle Papers, NPC 2/22. As kindly pointed out by the anonymous peer reviewer of this essay it is surprising that Newcastle seems to have travelled without a valet on this occasion.

There is a considerable literature on guidebooks in this period, imperfectly synthesised. See James Buzard, The Beaten Track: European Tourism, Literature, and the Ways to ‘Culture’ 1800–1918, Oxford 1993, pp.65–79; Alan Sillitoe, Leading the Blind: A Century of Guide Book Travel 1815–1914, London 1995, pp.74–117; Nicholas T. Parsons, Worth the Detour: A History of the Guidebook, Stroud 2007, pp.169–92; Jonathan Keates, The Portable Paradise: Baedeker, Murray, and the Victorian Guidebook, London 2011.

Galignani’s Traveller’s Guide through Italy was published in Paris in 1819 and reissued in several later, updated editions. This firm, which published unauthorised versions of works originally published in London, often by John Murray, also published from 1824 Galignani’s Messenger, an English-language newspaper aimed specifically at travellers. See Pine-Coffin 1974, p.181.

‘Posts’ were the places where horses were changed. Guidebooks listed them in detail so that travellers would know how far they would have to travel before they also were able to rest.

A diligence was a large carriage which was less comfortable because it lacked springs and was often over-crowded.

In 1840 Britain had 2,390 km of track, whereas Italy had a mere 20 (and in 1850 still only 620 km compared with Britain’s 9,797 km). Albert Schram, Railways and the Formation of the Italian State in the Nineteenth Century, Cambridge 1997, p.69, table 2.

As discussed by Sarah Hughes, ‘The Evolution of the Italian Phrasebook and Its Impact on British Travel to Italy, 1820–1940’, unpublished BA thesis, University of Nottingham 2012. I am grateful to Sarah Hughes for discussing this subject.

Richard Mullen and James Munson, The Smell of the Continent: The British Discover Europe, London 2009, pp.114–22.

M. Heafford (ed.), Two Victorian Ladies on the Continent: An Anonymous Journal, Cambridge 2008, p.111.

As stated in the ‘Notice to the Second Edition’ dated August 1846 on p.vi. The volume was issued in 1847.

Diary of Lord William Pelham-Clinton, 21 December 1839 to 2 August 1840, University of Nottingham, Newcastle Papers, Ne 2F/12.

Jousiffe 1840, p.36. This is the second edition, although no copies of the first appear to have survived.

Servants alongside itinerant workers were really the only British working-class travellers of this period. Susan Barton, Working-Class Organisations and Popular Tourism, 1840–1970, Manchester 2005, p.23 characterises their travelling experiences before 1850 as ones of ‘no Grand Tours’ and very limited leisure-travel at home.

Lady Theresa Lewis (ed.), Extracts of the journals and correspondence of Miss Berry: from the year 1783 to 1852, 3 vols., London 1865, vol.3, p.341.

The Landscape Annual for 1833, ‘The Tourist in Italy by Thomas Roscoe’, illustrated by J.D. Harding, London 1833.

James Johnson, Change of Air or the Diary of a Philosopher in Pursuit of Health and Recreation, 3rd edn, London 1831, p.228.

Anon. (Jane Waldie), Sketches Descriptive of Italy in the Years 1816 and 1817, London 1820, p.345. Compare Matthews 1820, p.380 on his prejudices against the French that direct experience only confirmed.

Ross Balzaretti is Associate Professor of History at the University of Nottingham.

Pietro Piana received his PhD from the University of Nottingham in July 2015.

Charles Watkins is Professor of Rural Geography at the University of Nottingham.

How to cite

Ross Balzaretti, Pietro Piana and Charles Watkins, ‘Travelling in Italy during Turner’s Lifetime’, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, September 2015, https://www