Joseph Mallord William Turner The Porta Nigra, Trier, from the North (outside the Gate) 1824

Image 1 of 2

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

The Porta Nigra, Trier, from the North (outside the Gate)

1824

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Folio 3 Recto:

The Porta Nigra, Trier, from the North (outside the Gate) 1824

D20141

Turner Bequest CCXVIII 3

Turner Bequest CCXVIII 3

Pencil, watercolour and chalk on white wove paper, 220 x 291 mm

Inscribed in red ink by Ruskin ‘3’ bottom right

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram bottom right

Stamped in black ‘CCXVIII–3’ bottom right

Inscribed in red ink by Ruskin ‘3’ bottom right

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram bottom right

Stamped in black ‘CCXVIII–3’ bottom right

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

References

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.II, p.683, as ‘The Porta Nigra, Trèves’.

1984

Gèrard Thill, Jean-Claude Muller and Jean Luc Koltz, J.M.W. Turner in Luxembourg and its neighbourhood, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Etat, Luxembourg 1984, p.103 no.38.

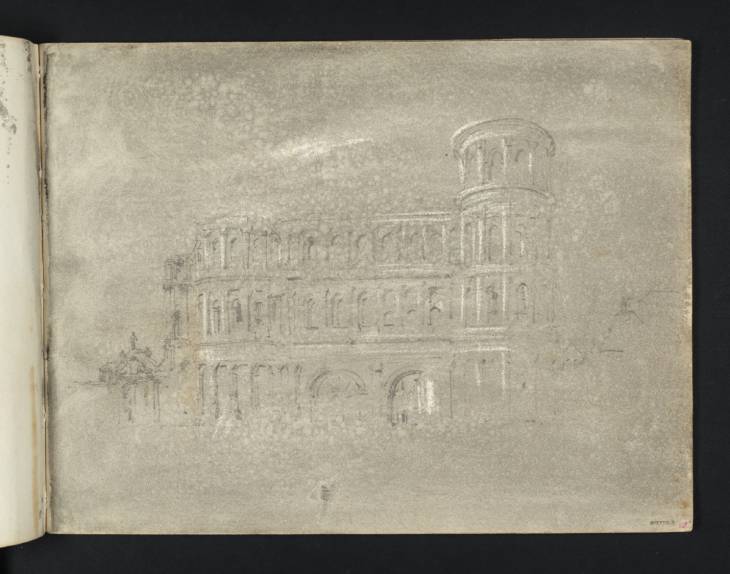

Carefully rendered in watercolour with fine and agile line, this drawing shows the Porta Nigra (Latin for ‘Black Gate’) at Trier, Germany. Constructed of grey sandstone that has blackened over centuries, the Porta Nigra was one of four gates erected by the Romans to defend the city from invasion. The travel writer Bartholomew Stritch, visiting Trier in the 1840s, found himself struck by the grandeur of the gate, remarking that the: ‘colossal and ebon black structure of the Porta Negra’ carried a ‘sombre air of remote antiquity’ and conveyed ‘an impression that is not speedily effaced from the memory of the spectator’.1 Stritch described the antiquity as a ‘sombre, imposing, and gigantic mass of masonry... built of immense blocks of stone, held together by bars of iron... in the form of a parallelogram’.2 It is ‘composed of two oblong towers connected by two ranges of galleries’ under which are ‘two lofty arched gates, which lead into the city’.3

A contemporary of Stritch, the author Michael Joseph Quin, wrote of the Porta Nigra in less laudatory terms. A ‘curious structure’, Quin writes, the gate was ‘evidently raised at a period when simplicity and true taste ceased to preside over the arts’.4 It:

abounds in halls and chambers, and galleries, for which no purpose can be assigned, except that of supplying to the citizens promenades where they might lounge in the heat of the day, or perhaps meet for the transaction of mercantile affairs, and at the same time enjoy charming prospects of the surrounding country and of the town itself.5

Here, Turner pictures the monument twenty years after Napoleon Bonaparte’s reconstruction of it. The Porta Nigra had for centuries served as a church, and was extensively remodelled in the medieval era to facilitate this ecclesiastical function. In 1804, however, the French Emperor ordered that the gate be converted back to its original Roman form and all its Christian accretions removed. This was to (re)secularise the Porta and to symbolically delete its associations with the Holy Roman Empire.6

Largely drawn with hairline strokes of black watercolour, Turner has employed chalk to highlight certain architectural aspects of the building as well as the fall of light. It also appears that the dappled effect seen above, below and to the right of the Porta Nigra has been achieved by dabbing the paper, saturated with wash, with a sponge.

Bartholomew Stritch, The Meuse, the Moselle, and the Rhine; or, A six weeks' tour through the finest river scenery in Europe, by B.S., London 1845, p.36.

Verso:

Blank

Alice Rylance-Watson

December 2013

How to cite

Alice Rylance-Watson, ‘The Porta Nigra, Trier, from the North (outside the Gate) 1824 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, December 2013, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, April 2015, https://www