Turner Bequest CXI

Pocket book, bound in red morocco, with pencil holder and one brass clasp

100 leaves of white wove paper

Approximate page size 110 x 88 mm

Made by William Balston at Springfield Mill, Maidstone, Kent, and watermarked ‘J. WHATMAN | 1808’

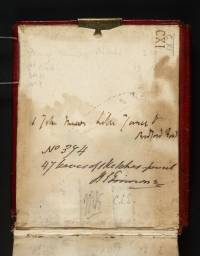

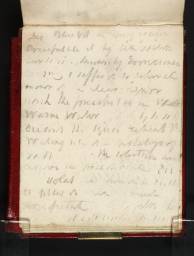

Endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest ‘No 394 | 47 leaves of sketches – pencil’ and signed by Henry Scott Trimmer in ink ‘H S Trimmer’ and by John Prescott Knight and Charles Lock Eastlake in pencil ‘JPL’ and ‘C.L.E.’ inside front cover (D07594)

100 leaves of white wove paper

Approximate page size 110 x 88 mm

Made by William Balston at Springfield Mill, Maidstone, Kent, and watermarked ‘J. WHATMAN | 1808’

Endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest ‘No 394 | 47 leaves of sketches – pencil’ and signed by Henry Scott Trimmer in ink ‘H S Trimmer’ and by John Prescott Knight and Charles Lock Eastlake in pencil ‘JPL’ and ‘C.L.E.’ inside front cover (D07594)

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

This little book must have spent some time in Turner’s pocket, being brought out for quick sketches and notes over a period of years. Sketches of Oxford were made just after Christmas 1809 in preparation for a picture for James Wyatt. Scenes around Hastings are datable to summer 1810 when Turner visited East Sussex to take up a commission from John Fuller of Rosehill (now Brightling) Park. As much a notebook as a sketchbook, Turner used it for poetry, accounts and memoranda relating to sales of pictures and engraving projects, and for personal notes. Issues reflected in these include the current fashion for the pictures of David Wilkie and Edward Bird, fuelled by the patronage of the Prince of Wales in 1810, the Prince’s failure to buy Turner’s Mercury and Herse despite having seemed to praise it in his speech at the 1811 Royal Academy dinner, and the financing of the Liber Studiorum. The overall date-range seems to be 1809–14.

A picture-dealer and framer in Oxford, Wyatt commissioned a picture of the city’s High Street in 1809. It was to be engraved, but at first it was undecided whether it was to be a painting or a watercolour. Although Turner already had an earlier drawing of the chosen viewpoint, looking up the High from between University and All Souls Colleges towards Carfax (Tate D08219; Turner Bequest CXX F), he needed up-to-date information and wrote to Wyatt at Christmas announcing his arrival in Oxford within the week. He asked Wyatt to have a large sheet of paper mounted on board1 and is said to have made a new drawing (currently untraced) from a post-chaise parked outside All Souls. The sketches in this book must have been made concurrently and be implicated in subsequent correspondence with Wyatt2 including queries about window-glazing, whether to include the Queen’s College or plan a companion picture looking in the opposite direction from Queen’s to Magdalen College. By March 1810 Turner had finished an oil painting, View of the High-Street, Oxford (Loyd Collection; on loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford).3 It did not include Queen’s.

Turner’s first commission from John Fuller for views in Sussex, initially for hire for engraving, came in spring 1810 and the same year he sold his picture Fishmarket on the Sands (William Rockhill Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri)4 to the same patron. By 1862, Fishmarket had acquired the additional title ‘Hastings’ and Butlin and Joll speculate that Turner told Fuller that it was set there in order to increase its appeal as Rosehill was barely ten miles away. Moreover Hastings was a fashionable subject following recent work by artists like the watercolourists Thomas Heaphy and Joshua Cristall. While Finberg was right to associate the numerous beach scenes in this sketchbook with Hastings, since the Stade and the cliffs of East Hill are clearly recognisable, Eric Shanes has doubted this location for the picture and there seems no real connection between them. The picture was exhibited at Turner’s Gallery, which opened on 7 May in 1810, but the sketches were presumably made during Turner’s visit to Sussex later that summer. Overlapping with other sketchbooks in use at the time, this one contains several views of Rosehill. Folios 20 verso–22 (D07623–D07625) have a panoramic view of the house and park that Turner repeated in a tighter, more finished study in his Views in Sussex sketchbook (Tate D10329; Turner Bequest CXXXVIII 10) and thereby made the basis of his painting for Fuller (private collection).5 Others are folios 61 and 65 (D07689, D07695). Folios 84 verso–85 (D07725–D07726) have a preliminary drawing of Somer Hill near Tonbridge, which Turner visited en route to Sussex. A larger version in the Vale of Heathfield sketchbook (Tate D10210–D10211; Turner Bequest CXXXVII 3a–4) was the origin of Somer-Hill, near Tunbridge, the Seat of W.F. Woodgate, Esq. (National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh)6 exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1811.

Turner’s presence around Hastings may have been prompted by more than his current work for Fuller. In 1811 Sarah Danby gave birth to Georgiana, the second of her two daughters supposedly by Turner. Years later, Georgiana said she had been born in ‘Surrey’ but may have mistaken it for Sussex. Georgiana’s older sister, Evelina, was baptised at Guestling near Hastings in 1801, and ‘Guestling. Calld 3 Oaks’ is written on folio 99 (D07751). Noting these suggestive coincidences, Anthony Bailey wonders if the ‘Platt’ and Mrs W’ mentioned with ‘Mrs D’ inside the front cover (D07594) are a doctor and midwife. Turner may have needed a doctor himself as on folio 8 verso and recto (D07606–D07605) he has scrawled a cure for gonorrhoea as prescribed by the surgeon Jesse Foot. Instructions for smoking stramonium are written nearby, on folio 2 verso (D07597). Turner liked to jot down remedies, whether or not for ailments of his own, and Bailey suggests that his use of this ‘herb’ was homoeopathic. Derived from the poisonous datura plant, it can help to treat asthma but is also a powerful (even fatal) hallucinogenic. Was Turner using it a pain-killer? Or still more dangerously as an aid to inspiration?

James Hamilton suggests that an overdose of stramonium produced the wearily introspective ode on death or suicide beginning ‘World I have known thee long...’ and ending with regret that ‘few there be who weave | Wreaths for the Poet brow’, on folio 66 verso (D07698). The book is rich in drafts of poetry, some of it gruesomely bloodthirsty and written while Turner worked on his picture Apollo and Python (Tate N00488)7 for the 1811 Royal Academy. Hamilton sees this picture of the god slaying a writhing dragon as a metaphor for the artist’s revenge on his critics. Turner showed it with his own adaptation of lines from Matthew Prior’s translation of Callimachus’s Hymn to Apollo which he cites on folio 70 verso (D07704). On folio 17 (D07617) he echoes John Dryden’s translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Dryden’s ‘expiring serpent wallow’s in his gore’ becoming ‘till the monster weltered in his gore’.

As god of poetry and music as well as light, Apollo prompts Turner to verses on creative inspiration, contrasting fancy and imagination. His starting point is the Sussex poet Thomas Otway who he says was born ‘By Arun[‘s] sedgy stream’ (actually at Milland, in Sussex but a long way from this river):

Mark Akenside’s Pleasures of Imagination (1744/57) and Dr Langhorne’s Visions of Fancy (1762) are more grist to Turner’s mill, as is an historical span of voyagers and adventurers from Columbus and Sir Walter Ralegh to James Bruce, explorer of the Nile. Bruce’s description in his Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (1790) of his quest as a ‘violent effort of a distempered fancy’, his ‘unquiet and imperfect sleep’ and ‘phantoms that, while in bed, had oppressed and tormented me’8 seems to have suggested some of Turner’s writing. As Turner pictures his travellers led by fancy into delusion and danger, he gets completely carried away (by stramonium again?), leaving behind his usual Augustan harmonies for a throbbing metre and the Romantic restlessness of a Samuel Taylor Coleridge or Thomas De Quincey. The poet and his heroes are suddenly beset by

...devils when all in the feverish night

When the livid dog star rages denying rest

To the weak Eyelids that the noon tide beam

Has glared to nothingness

(folio 94, D07744)

When the livid dog star rages denying rest

To the weak Eyelids that the noon tide beam

Has glared to nothingness

(folio 94, D07744)

This draft poem ends on folio 92 verso (D07741) with Ralegh in prison, writing his History of the World (1614) as a riposte to James I who had imprisoned him for treason. Poet as well as adventurer, Ralegh took literary revenge on his oppressor, thus perhaps seeming an historical counterpart to the mythic Apollo slaying the dragon. However, he was executed and might be the poet Turner imagines saying his farewells. The vein of pessimism running through Turner’s thoughts anticipates The Fallacies of Hope, the supposedly longer epic he first quoted in the Royal Academy catalogue in 1812, adapting a phrase from Langhorne’s Visions.

Clearly, professional ups and downs have contributed to Turner’s mood. On folio 68 verso (D07701) he copies out from The Sun John Taylor’s flattering review of Mercury and Herse (on the London art market in 2005),9 his other historical exhibit at the 1811 Academy along with Apollo and Python. However, a mistaken rumour that the Prince Regent wanted to buy it and competing interest from other important collectors soon put Turner in such an awkward position that he could not sell it at all, a ‘victim of etiquette’ as Taylor wrote the following year. In a short verse on the genre painters David Wilkie and Edward Bird, Turner comments acidly on flattery and the whims of patrons:

Coarse Flattery, like a Gipsey came

Would she were never heard

And muddled all the fecund brains

Of Wilky and of Bird

(folio 65 verso, D07696)

Would she were never heard

And muddled all the fecund brains

Of Wilky and of Bird

(folio 65 verso, D07696)

Both these artists had been hyped, Wilkie especially by Sir George Beaumont who was also highly critical of Turner’s work. The Prince of Wales’s purchase of Bird’s Country Choristers from the Academy in 1810 and commission to Wilkie for a companion picture, Blind Man’s Buff (both Royal Collection) must have been galling when Turner had won no such recognition – and the more so the following year when the Prince did not buy his Mercury and Herse. A sudden interest in Wilkie’s work from Turner’s patrons Fuller and the Earl of Essex, when the latter had recently dropped a likely commission for Turner’s Wilkie-like Harvest Home (Tate N00562),10 could also have unsettled Turner at this time.

Among various notes culled from The Elements of Architecture (1624) by Sir Henry Wotton (called by Turner ‘Sir Billy’, folio 90, D07736) is a plea to the critic to ‘examine himself’ before attacking others’ work – an appealing argument for a sensitive artist and one that chimes with the attacks on critical vanity that Turner had already enjoyed in Martin Archer Shee’s Rhymes on Art (1805). Wotton’s book, with its wealth of reference from Vitruvius to Vasari, Quintilian to Palladio, was one of many that Turner consulted while preparing his lectures as Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy, given from 1811. His notes range from ancient artists to Renaissance architecture and sculpture and address aesthetic theory such as the Vitruvian concept of architecture as bodily representation (folio 89, D07734). Particularly relevant to perspective is Palladio’s advice (also derived from Vitruvius) to adjust the angle and proportion of sculpted figures when set high on a building (folios 90–89 verso, D07736–D07735).

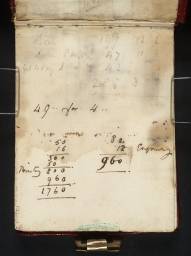

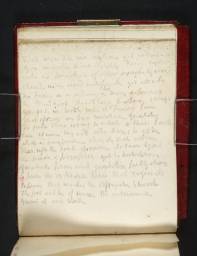

Of the various financial notes in the book, some concern the Liber Studiorum, Turner’s series of representative landscapes. On folio 1 (D07595) he records a payment to James Lahee, the printer of the plates, while on folios 96 verso–97 verso (D07747–D07749) he sets out the financing of the project and the impact of a rise in price on its profitability, and proposes issuing extra so-called proofs. Discussing these figures, Finberg and Gillian Forrester reach different conclusions, not least in dating, the former assigning them to early in 1809 and the latter arguing that they may be later. Turner mentions three prints going to ‘Holworthy’, presumably the artist James Holworthy who paid for a first number of the Liber on 19 March 1814, as observed by John Gage who, nevertheless, dates Holworthy’s appearance in this sketchbook to 1811.11 Overall, the figures give a very optimistic forecast of a profit of £3,475 but as Forrester shows, Turner has made some unrealistic assumptions and elsewhere he estimates the ‘Probable Advantage of the Liber Studiorum’ at the lower (but still unlikely) sum of £2,000 (Tate D40900).12

If there is some doubt about when Turner made his Liber calculations, other figures are dated or datable. Totting up his income from the sale of pictures in 1810 on folio 59 (D07868) he lists purchasers and patrons; Sir George Phillips, the Earls of Egremont and Lonsdale, the Hon. Charles Pelham and John Fuller. Differences between sums received and the actual price of the pictures can be explained by additional charges for framing, packing or delivery, as well as the expression of sums in pounds rather than guineas. Some of these sums correspond to records in the Finance sketchbook of transactions with Turner’s stockbroker, William Marsh. A draft or copy of a sale advertisement for property in Norton Street, Marylebone on folios 62 verso–63 (D07691–D07692) is dated Thursday 9 August; this date fell on a Thursday in 1810.

Forrester suggests that other figures, for example on folios 1 and 42 verso (D077657), relate to George and William Bernard Cooke’s Picturesque Views on the Southern Coast of England (1814–26), in the planning when this sketchbook was in use. Notes on the geology of the south coast on folios 3 verso–5 (D07599–D07602) and the history of St Michael’s Mount inside the back cover (D40662) must also be connected with it. So far, these have not been traced to a published source but as always Turner read widely around his subject.

Loose, folded sheet in the Finance sketchbook (Tate D08283–D08359; D40898–D40901; D41431; Turner Bequest CXXII).

Technical notes

How to cite

David Blayney Brown, ‘Hastings sketchbook c.1809–14’, sketchbook, May 2011, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www