Draughtsman and Watercolourist

David Blayney Brown

Turner was a master draughtsman and the outstanding watercolourist of his generation, renowned as a technical prodigy. David Blayney Brown surveys Turner’s stylistic and technical development over his long career, examining his production of sketchbooks, independent and intermediate colour studies, and finished watercolours for exhibition and engraving.

Tate’s collection of sketchbooks, drawings and watercolour by Turner comes very largely from the Turner Bequest and consists of working materials more than works that Turner finished, exhibited or sold. Finished and exhibited watercolours are present, especially from Turner’s earlier years, and there are numerous examples of drawings made for the engraver. Notable works have been acquired for Tate’s collection before the accession of the Bequest and afterwards to amplify it. But the distinctive character of the collection, and its uniqueness as a representation of works on paper by a single artist, is perhaps best defined by its vast array of pencil or coloured sketches, handwritten notes and studies of a private, personal or even intimate kind. Just as the oil sketches, experiments and works in progress that survive from Turner’s studio underpin his exhibited pictures, many thousands of works on paper provide the hinterland to both paintings and finished watercolours and offer unique insights into a great artist’s mind and methods.

Sketchbooks

Selection of sketchbooks from the Turner Bequest

Courtesy of Matthew Imms

Fig.1

Selection of sketchbooks from the Turner Bequest

Courtesy of Matthew Imms

Turner was always alert to technical developments, whether in papermaking or pigments, and was innovative or improvisatory in his use of them. He might buy a drawing book from a supplier or binder but was as likely to have leaves bound for him, or even to stitch them together himself between paper-wrapped boards. When he intended to use a sketchbook for coloured drawings, or planned to work outdoors and needed to reduce the glare of sunlight on the paper, he had the leaves tinted or did the job himself, with various solutions such as India ink and tobacco-water (some sketchbooks still smell of tobacco) or the soot-water then recommended for the purpose as well as coloured, mid-tone washes. Later he favoured grey grounds. Often, however, he used the natural colour of the paper as an integral part of his design, especially when working in watercolour in the later years of his life. When travelling, he took the opportunity to buy new, foreign-made papers.

Turner’s sketchbooks range from some of the largest, most luxurious and expensive then on the market, thick, calf-bound tomes with brass clasps, to soft-bound, flexible ones that could be kept rolled. They often contain the smoother wove papers developed in the later eighteenth century as an improvement on longer-established laid papers. These were good for watercolour as well as pencil or chalks. As research by Peter Bower has shown, the best British and European papermakers of the day are amply represented in Turner’s sketchbooks, as they are across the entire Bequest. But, as is also the case throughout the Bequest, the sketchbooks are not only made up of artist’s papers. Turner was often content to shop at a stationer’s and used a great variety of smaller books such as diaries, pocket or account books that contained everyday writing papers. From time to time he tried out papers originally made for other purposes, such as bank notes, and bought different varieties direct from paper mills.2 A wide range of papers were perfectly adequate for quick sketching in pencil and in any case Turner did not use them only for drawing. The term ‘sketchbook’ must be applied generically in relation to the Bequest as some were used mainly as notebooks. They contain jottings on a wide range of subjects, from drafts of poetry to notes for lectures or on finances, business and domestic matters, recipes and medical prescriptions as well as sketches. Such books are usually small and Turner was probably rarely without one or two in his coat-pocket, ready for use at any time. This would explain the random nature of the content, and its tendency to run across wide spans of time.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Copy of Wilson's 'The Convent on the Rock' 1796–7 from the Wilson sketchbook

Gouache, graphite and watercolour on paper

113 x 93 mm

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.2

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Copy of Wilson's 'The Convent on the Rock' 1796–7 from the Wilson sketchbook

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Lacy's Court, Bath Street, Abingdon c.1789 from the Oxford sketchbook

Graphite and watercolour on paper

160 x 250 mm

Tate D00014

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.3

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Lacy's Court, Bath Street, Abingdon c.1789 from the Oxford sketchbook

Tate D00014

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Storm Clouds, Looking Out to Sea 1845 from the Ambleteuse and Wimereux sketchbook

Watercolour on paper

238 x 336 mm

Tate D35397

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.4

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Storm Clouds, Looking Out to Sea 1845 from the Ambleteuse and Wimereux sketchbook

Tate D35397

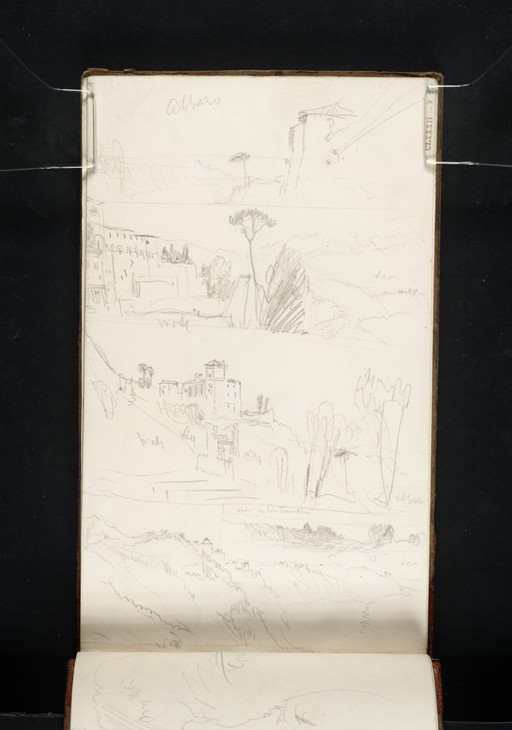

On major tours Turner tended to carry a number of sketchbooks and sometimes acquired more as he needed them en route, firstly in 1802 when he topped up his stock of English-made books with ones bought in Paris and Berne. They might range from small pocket books in which he noted his first impressions in pencil or ink, to much larger ones in which he explored their pictorial potential in coloured or composition studies. These might also interact with drawings made on even bigger loose sheets, which he carried in a portfolio. This practice of working across a range of materials was developed during early tours to the North of England, Wales and Scotland and reached something of a climax on the first Swiss tour in 1802. As he grew older Turner favoured smaller books for pencil sketching and larger soft-bound ones for watercolour. His use of pencil turned from clear outline and tonal shading into a highly characteristic shorthand, which could capture essentials with great speed and economy or combine a run of sketches on a single page like shots on a roll of film. Larger, landscape-format pages encouraged work with the brush and an expressive use of colour over minimal, but still precise, outline. Among many other examples, Turner’s highly focused pencil notation and broader coloured sketching can be found in sketchbooks used during his first visit to Italy in 1819 (figs.5, 6).

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Five Sketches of Lake Albano, Including the Monastery and Tomb at Palazzola 1819 from the Albano, Nemi, Rome sketchbook

Graphite on paper

189 x 113 mm

Tate D15311

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.5

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Five Sketches of Lake Albano, Including the Monastery and Tomb at Palazzola 1819 from the Albano, Nemi, Rome sketchbook

Tate D15311

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Lake Como 1819 from the Como and Venice sketchbook

Watercolour on paper

224 x 290 mm

Tate D15251

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.6

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Lake Como 1819 from the Como and Venice sketchbook

Tate D15251

Touring, rather than casual sketching of his day-to-day life, was always the main motive for Turner’s use of sketchbooks and for the technical and stylistic developments contained therein.

Much of Turner’s early travelling was undertaken in anticipation of, or as a response to commissions for topographical illustrations and prints. Such projects continued well into the 1830s along with the need to collect material for pictures for exhibition or watercolours for collectors. For Turner, his sketchbooks constituted a reference library of images, to source a subject or spark his imagination. When commissioned to make topographical watercolours for an engraver or publisher, for series such as Picturesque Views in England and Wales, he would look through a relevant sketchbook for the places and drawings required (which might have been made years earlier) and then develop his final watercolours through intermediate composition sketches or coloured studies. Splashes of colour from these or even from the final watercolour while it was in progress can sometimes be found on sketchbook pages, indicating that Turner also had his first sketch beside him as he worked. Often, as Sam Smiles has observed, he took initial inspiration from small, quick sketches rather than larger or more careful ones, suggesting that they served to ‘conjure the spirit of the landscape’ and ‘engage rather than restrain his imagination’.4

Turner quickly got into the habit of writing the names of key places represented in a sketchbook, or the rough outline of a tour, inside or outside the covers or on the spine, sometimes on a paper label. As sketchbooks accumulated in his studio, he began numbering them. Generally, he regarded them as a private resource. While he clearly valued him he did not treat them as sacrosanct, tearing out pages before use (single sketches are apt to spread across successive pages), breaking up books afterwards or leaving only some of their contents intact. He moved some of the finest drawings and coloured studies made on tour in 1802 from sketchbooks into an album, labeled with their titles, to show clients whose initials he noted alongside when he obtained commissions. While even the most evolved drawings in sketchbooks were only means to an end, Turner did sometimes allow privileged individuals like Ruskin to choose selected pages, and is known to have given an entire sketchbook to his friend and patron H.A.J. Munro of Novar, indicating that he ‘was prepared to countenance a limited dispersal of such work’.5 Whether this meant that he also came to allow it aesthetic value in its own right is a moot point. It seems at least as significant that he made no specific provision for sketchbooks, or indeed for any of the many thousands of drawings and watercolours in his studio. Either he did not much care about their fate or he assumed that his executors would deal with them as they saw fit, as turned out to be the case. Today, very few sketchbooks are untouched or exactly as Turner left them. But while they have undergone various interventions since, they are certainly in better condition than they were found after his death.

Drawing and painting in watercolour

From Turner’s beginnings as an artist, drawing architecture, topography or the human figure from casts or life in the Royal Academy Schools, the subjects, media and techniques found in the sketchbooks were amplified on separate sheets of paper. He launched his career as a watercolourist, producing picturesque views and antiquarian subjects, and like all artists at the time, learned by example. In 1789, aged fourteen, he was working for the architectural draughtsman Thomas Malton, whom he later described as his ‘real master’, helping to draw buildings in colourful landscape settings. He also worked in the drawing offices of several architects, operating on what Greg Smith has described as ‘the fluid border between architect and artist, which stemmed from shared skills’.6 These included not only perspective and the ability to draw plans and elevations but the typical watercolour method of the period, tinting drawn outlines with touches of bright local colour applied over a ground of grey or grey-blue wash. This ground served as a mid tone on the white or off-white papers Turner used for his early watercolours.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 558

An Octagonal Turret and Battlemented Wall: Study of Part of the Gateway of Battle Abbey, after Michael Angelo Rooker 1792–3

Graphite and watercolour on paper

172 x 146 mm

Tate D00193

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.7

Joseph Mallord William Turner

An Octagonal Turret and Battlemented Wall: Study of Part of the Gateway of Battle Abbey, after Michael Angelo Rooker 1792–3

Tate D00193

Just how quickly Turner advanced from the conventional ‘tinted drawing’ – the staple of the topographers – to composing and thinking with the brush can be seen in large, ambitious colour studies that from the later 1790s supplemented material in the sketchbooks he took with him to the North of England or Wales (fig.8). Their dramatic effects of weather and light are expressed in dynamic brushwork and resonant tones more like those of oil than water-based media. Turner’s spell of study at Monro’s coincided with his first efforts as a painter in oil, and experiments in tonal contrast and chiaroscuro dating from the middle of the decade, though trialled on paper, can be related to early oils including his first Royal Academy exhibit in 1796, a moonlit marine. Working across both media, Turner realised that tones could be modulated in what was effectively the reverse of watercolour scale practice, reduced from dark to light on paper just as they were in oils. Whereas his earlier sketchbooks had been filled with pencil drawings to which he sometimes added watercolour tints or washes, he began washing some of their pages with grey or brown over which he worked in pencil, chalk, watercolour or gouache and scratched or rubbed out highlights. Working on larger, independent sheets of paper he added many layers and combinations of wash but also made exceptional use of these scraping and mopping techniques, which could include using his finger nails, brush handles, absorbent breadcrumbs or damp cloths. In finished watercolours, he harmonised the whole design by brushing layers of sombre-toned washes over a foreground or middle distance.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Caernarvon Castle, North Wales exhibited 1800

Watercolour on paper

706 x 1055 mm

Tate D04164

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.9

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Caernarvon Castle, North Wales exhibited 1800

Tate D04164

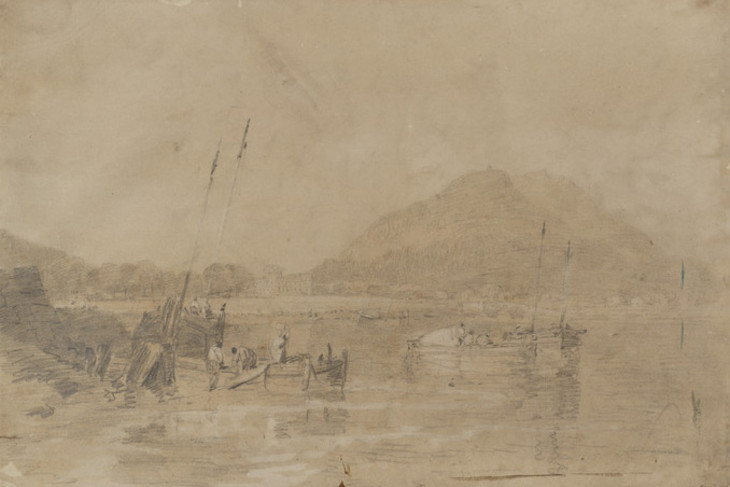

Tours of Wales in the late 1790s, Scotland in 1801 and his first visit to mainland Europe, to France and the Swiss Alps in 1802, introduced Turner to the raw materials of some of his finest watercolours – lakes and mountains dramatised by weather and light. He rendered them in subdued colours, quite unlike the dazzling tints of his later watercolours and perhaps affected by the foreboding visual language of the eighteenth-century sublime. In Scotland and Switzerland he also made monochrome studies in pencil or chalk, heightened with white gouache, on tinted paper, often repeating smaller pencil sketches in his sketchbooks in terms of tone and texture (figs.10, 11). These may have taken their inspiration from earlier black chalk drawings by Richard Wilson, which Turner knew from Monro’s collection and through Wilson’s pupil Farington, and of which he later owned at least one example. As records of scenic touring they could be shown to prospective clients, who presumably looked mainly at their subjects and compositions. For Turner himself, they helped sharpen his visual memory for colour, in effect by its very absence. While he did not make drawings quite like these again, he became less dependent on coloured sketches from nature and even came, in mid-life, to begrudge the time they took to make. When he coloured his drawings, he often did so afterwards, working on them in batches, and using a limited range of greys, blues and a little yellow and adding white gouache for highlights. Working towards a watercolour for a client, he might make a separate colour study in brighter colours to decide the chromatic scale and lighting scheme; sometimes these have additional colour trials in the margins.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Inveraray Castle and Duniquoich Hill from across Loch Shira, Loch Fyne c.1801

Gouache and graphite on paper

332 x 485 mm

Tate D03388

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.10

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Inveraray Castle and Duniquoich Hill from across Loch Shira, Loch Fyne c.1801

Tate D03388

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Lake of Brienz from the Quay 1802 from the Grenoble sketchbook

Chalk, gouache and graphite on paper

216 x 283 mm

Tate D04536

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.11

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Lake of Brienz from the Quay 1802 from the Grenoble sketchbook

Tate D04536

Hence it was hardly ever the case that Turner simply ‘drove his colours about’11 until he arrived at what he wanted, although to encourage that illusion can only have added to his reputation as a prodigy. Exhibition watercolours of Alpine subjects based on his tour in 1802 (fig.12) are technical tours de force, extraordinarily elaborate yet at the same time austere and grand, and less finished or intermediate versions of similar subjects demonstrate how carefully they must have been prepared (fig.13). No sooner, however, had he brought watercolour to a level of equality with oil than Turner returned to exploring its own distinctive qualities, transparency and capacity for intimacy and freshness. Working in both media on the same subjects at the same time, outdoors from nature along the Thames where he rented out-of-town lodgings at Syon, Hammersmith and Twickenham from 1804, his methods were the same; but his understanding of watercolour on paper once again conditioned his use of oil, rather than the other way around. Just as he laid watercolour thinly, leaving the paper bare or exposing it to give highlights or reflections, so he brushed oils over an off-white preparation on canvas or board. The results show a new feeling for naturalism and the cool and luminous tonality that earned him the description of ‘white painter’. This soubriquet (intended as an insult) was usually applied to his oil paintings, but his most interesting technical experiments tended increasingly to be carried out on paper while traditional boundaries between oil and water were eroded or dissolved.12

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Battle of Fort Rock, Val d'Aouste, Piedmont, 1796 exhibited 1815

Gouache and watercolour on paper

696 x 1015 mm

Tate D04900

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.12

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Battle of Fort Rock, Val d'Aouste, Piedmont, 1796 exhibited 1815

Tate D04900

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The St Gotthard Road between Amsteg and Wassen looking up the Reuss Valley c.1803 or 1814–15

Gouache, graphite and watercolour on paper

675 x 1010 mm

Tate D04897

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.13

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The St Gotthard Road between Amsteg and Wassen looking up the Reuss Valley c.1803 or 1814–15

Tate D04897

If Turner’s media and techniques were in constant flux, in response to the task in hand or to actual or emotional experience, his choice of colour was no less various. It was instinctive and emotional, learned and theoretical, but above all pragmatic and rooted in practical experience. Well-versed in theories of optics, historical and contemporary, he was fascinated by the interplay of aerial colour (created by the operation of light) and material colour (made by pigments). He took full advantage of new colours as they became available, such as the ready-made watercolour cakes introduced by Thomas and William Reeves in 1781 and industrially-produced Mars colours which gave bright, earthy tones. When he was young, the absence of any true bright green required Turner, like all other artists, to mix it, usually by brown ochres in thinned Prussian blue which, with lead white, ultramarine, indigo, yellow ochre, red lead, vermilion and madder was already well-established.13 Cobalt blue and chrome yellow appeared after 1810, pale chrome in the next decade, viridian and emerald green in the 1830s and scarlet in the 1840s.

Such growing abundance only sharpened Turner’s speculations, later in life, as to the number of true ‘primary’ colours and his interest in the contrasting emotive powers of each end of the spectrum. He explored how colours changed, were in effect created in relation to others, or affected mood. Broadly, his palette, both in water-based media and oils, brightened over time but he could suddenly revert to the darker end of the spectrum or veer from naturalistic to deliberately artificial colour according to the subjects he was working on. While he used earthy, outdoor tints for his Thames sketches (fig.14), he chose a restricted palette of sepia, umbers, siennas and ochre for the landscape subjects for his Liber Studiorum (Book of Studies), thereby anticipating the shadowy chiaroscuro of mezzotint in which they were to be reproduced and the lyrical idealism of many of the compositions (fig.15). Later he took to setting his engravers the challenge of expressing, in black and white line, designs painted in blazing, extravagant colours far beyond reality. These extremes of restraint and recklessness can often, but not always, be justified by circumstance; they seem also to respond to the introvert and extrovert aspects so evident in his personality. If the gulf between them seems unbridgeable, Ruskin’s perceptive comment that Turner painted in colour but thought in light and shade suggests a common denominator.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The River Thames and Kew Bridge, with Brentford Eyot in the Foreground and Strand-on-Green Seen through the Arches: Low Tide Thames 1805 from the Reading to Walton sketchbook

Graphite and watercolour on paper

256 x 364 mm

Tate D05946

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.14

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The River Thames and Kew Bridge, with Brentford Eyot in the Foreground and Strand-on-Green Seen through the Arches: Low Tide Thames 1805 from the Reading to Walton sketchbook

Tate D05946

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Bridge and Goats c.1806–7 from the Liber Studiorum

Etching and watercolour on paper

180 x 250 mm

Tate D08147

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.15

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Bridge and Goats c.1806–7 from the Liber Studiorum

Tate D08147

Turner gave as much thought to the working materials he made for himself as to those he made for engravers. His first large topographical series, Picturesque Views on the Southern Coast of England commissioned in 1811 and a related Rivers of Devon prompted a long campaign of research and preparation beginning with touring and using his sketchbooks on the spot. As well as final watercolours made for reproduction, Turner made independent studies in broad, often muted washes (sometimes tested in the margin). These served for future reference, for paintings or as exercises, getting him into the spirit of the locale (fig.16). His first systematic use of colour studies to set out a chromatic plan seems to have been for another topographical commission, Dr. Thomas Whitaker’s History of Richmondshire, while he first used the term ‘beginning’ for a rough coloured sketch (fig.17) for a watercolour of a sinking ship, made for another Yorkshire patron, Walter Fawkes. Unlike these, the papers ‘tinted with pink and blue and yellow’ that Fawkes’s daughters remembered hanging to dry on cords in Turner’s bedroom at Farnley in 181614 sound like underpaintings, to be worked up later, or trials of colour or brushwork. Turner made many coloured sketches for their own sake, to record passing effects or ideas or experiment with colour and paint, and their impact on his public or published work, if any, must have been more cumulative than specific. As Eric Shanes has pointed out, the hundreds of works in the Bequest named by A.J. Finberg ‘Colour Beginnings’ or ‘Miscellaneous: Colour’ fall into more distinctly recognisable categories, preparatory, exploratory or independent. Collectively, Shanes prefers to characterise them as ‘explorations’, and to distinguish ‘studies’ (made for known, finished works) from ‘sketches’ that were taken no further and remain entities in themselves.15

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Hulks on the Tamar: Twilight c.1813

Gouache and watercolour on paper

262 x 330 mm

Tate D17169

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.16

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Hulks on the Tamar: Twilight c.1813

Tate D17169

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Beginning for 'Loss of an East Indiaman' c.1818

Graphite, watercolour and chalk on paper

311 x 460 mm

Tate D17178

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.17

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Beginning for 'Loss of an East Indiaman' c.1818

Tate D17178

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Burg Sooneck with Bacharach in the Distance: Large Colour Study c.1819–20

Watercolour on paper

support: 403 x 567 mm

Tate D25304

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.18

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Burg Sooneck with Bacharach in the Distance: Large Colour Study c.1819–20

Tate D25304

Transparent and opaque; watercolour and gouache

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

View of the Arch of Titus and the Temple of Venus and Roma, from the Arch of Constantine and the Meta Sudans, Rome 1819 from the Rome: Colour Studies sketchbook

Gouache, graphite and watercolour on paper

225 x 367 mm

Tate D16367

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.19

Joseph Mallord William Turner

View of the Arch of Titus and the Temple of Venus and Roma, from the Arch of Constantine and the Meta Sudans, Rome 1819 from the Rome: Colour Studies sketchbook

Tate D16367

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Somerset Room: Looking into the Square Dining Room and beyond to the Grand Staircase

Watercolour and bodycolour on paper

139 x 189 mm

Tate D22735

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.20

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Somerset Room: Looking into the Square Dining Room and beyond to the Grand Staircase

Tate D22735

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Paris from the Barrière de Passy c.1833

Gouache and watercolour on paper

143 x 194 mm

Tate D24682

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.21

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Paris from the Barrière de Passy c.1833

Tate D24682

The French subjects were the only instances when Turner used gouache for engraving. Elsewhere, in informal sketches of central European or Mediterranean subjects, it appears in ever more intense, sometimes almost hallucinogenic colours. By contrast, Turner’s watercolours of (mainly) English topography showed subtlety and restraint. In the 1820s and 1830s the medium reached a new level of refinement in finished works for the engraver, such as the series of The Rivers and Ports of England commissioned like the earlier Southern Coast by W.B. Cooke (fig.22). These watercolours blend expansive perspectives with a wealth of life and detail. Laid in first with generous fields of wash, they were worked up with very fine brushes with layers of delicate hatching and stippled with points of brilliant, jewel-like colour. The process looks painstaking but was probably (as with the Fawkes man-of-war) the work of hours rather than days, for as the painter James Orrock remembered being told by one of Turner’s colleagues, the master’s mature practice was ‘prodigiously rapid’ and involved working on several subjects at a time, the papers stretched on boards with a convenient handle on the back:

After plunging them into water, he dropped the colours onto the paper while it was wet, making marblings and gradations throughout ... His completing process was marvellously rapid, for he indicated his masses and incidents, took out half-lights, scraped out high-lights and dragged, hatched and stippled until the design was finished. This swiftness, grounded in the scale practice in early life, enabled Turner to preserve the purity and luminosity of his work, and to paint at a prodigiously rapid rate.20

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

A Villa. Moon-Light (A Villa on the Night of a Festa di Ballo), for Rogers's 'Italy' c.1826–7

Pen and ink, graphite and watercolour on paper

support: 246 x 309 mm

Tate D27682

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.23

Joseph Mallord William Turner

A Villa. Moon-Light (A Villa on the Night of a Festa di Ballo), for Rogers's 'Italy' c.1826–7

Tate D27682

Synthesis, transformation and controversy: Turner’s later watercolours

Rogers told a collector friend that the original designs for his poem Italy were returned to Turner after engraving because ‘the truth is, they were of little value as drawings’.22 This is unlikely to have distressed the artist, who regarded his works for the engraver as functional objects and the resulting prints as the real works of art. However, many of Turner’s designs for prints were exhibited in his lifetime, to promote the publications for which they were made, and while many stayed in his possession, exceptional examplesbecame sought-after collectables (Tate possesses only two engraved subjects from England and Wales, neither from the Bequest). Exhibitions like those held by the Cookes in Soho Square, Heath at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly and Moon, Boys and Graves in Pall Mall were important occasions because Turner was exhibiting so few watercolours himself, for the very reason that he was making most of them for reproduction. Fortunately, the last watercolour he sent to the Royal Academy, The Funeral of Sir Thomas Lawrence exhibited in 1830 (fig.24), is in the Bequest, as are colour studies for what seems to have been his final exhibited watercolour, Bamburgh Castle – perhaps an unused subject from England and Wales – shown at the Graphic Society in 1837. In a continuing demonstration of Turner’s varied methods, The Funeral was subtitled ‘A Sketch from Memory’, implying an immediacy and haste that is very evident in the work; colour trials surround its margins, on a backing sheet, indicating that it was painted from scratch. The Bamburgh studies, on the other hand, progress their subject through successive stages (fig.25).

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Funeral of Sir Thomas Lawrence: A Sketch from Memory exhibited 1830

Watercolour and bodycolour on paper

561 x 769 mm

Tate D25467

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.24

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Funeral of Sir Thomas Lawrence: A Sketch from Memory exhibited 1830

Tate D25467

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland: Preparatory Study c.1837

Graphite and watercolour on paper

459 x 769 mm

Tate D36321

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.25

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland: Preparatory Study c.1837

Tate D36321

The last decade of Turner’s working life, into the mid-1840s, saw an outburst of work in watercolour and the astonishing technical flowering that has won him his modern reputation as the supreme master of the medium. It is the more remarkable that this was achieved against a backdrop of changing tastes and clientele and an adverse trend of criticism that may have made him wary of showing his latest watercolours widely in public. This had been evident even in the generally enthusiastic reviews of Fawkes’s exhibitions of his collection in 1819 and 1820, while Turner’s Italian visit in 1819 appeared to mark a watershed when his earlier ‘natural, simple and effective’ works began to give way to ‘a thousand yellow fantasies and crimson conceits’.23 Greg Smith’s analysis of printed criticism of Turner’s watercolours in 1819 and 1820, and of subsequent publishers’ exhibitions, has revealed the breakdown of positive consensus in the face of a growing realisation that special allowances had to be made for Turner’s exceptionalism; and moreover, that the ‘broadly associative’ reading of his landscapes in which colour was thought to underpin morality, sentiment and ‘presiding mental purpose’24 was ill-equipped to deal with colouring that threatened instead to become ‘an idiosyncratic element of handling’.25 As but one example, watercolours shown at Moon, Boys and Graves in 1833 attracted comment for their sometimes high colour. England and Wales, for which many had been made, proved to be a commercial failure – though for the different reason that as a designer of topography Turner was now a victim of his own success, with so many prints after his work already on the market and depressing demand.

In retrospect, the tensions of these later years can seem a blessing in disguise. As the pressure of big print projects lifted and criticism became more pointed, Turner’s private output became more prolific and relaxed. A tour through France to Switzerland with Munro of Novar (himself an amateur artist) in 1836 is a good indicator of Turner’s graphic practices when working informally at this time. He filled two sketchbooks with quick, concise pencil sketches set out several to a page in his typical shorthand. Munro told Ruskin, ‘wherever he could get a few minutes, he had his little sketch book out, many being remarkable, but he seemed to tire at last and got careless ... I don’t remember colouring coming out till we got into Switzerland’. When it did, Turner used a sponge to create ‘misty and aerial effects’.26 Munro’s recollections would seem to contradict a claim by Ruskin that Turner never used watercolour on the spot, and indeed Ruskin related an occasion on the same tour when Munro got into difficulties with an outdoor sketch and Turner borrowed his sketchbook to make three progress sketches, to show his friend ‘the process of colouring from beginning to end’.27 In Switzerland or Venice (fig.26) colour is integral to Turner’s response and it appears that he had outgrown his earlier reservations about colouring versus pencil sketching before the motif. Perhaps time was less an issue; he could work faster than ever; and ‘on the spot’ might now include a window or a hotel balcony, where he could sit comfortably out of direct glare. Wherever it was done, Turner’s watercolour sketching from the late 1830s distilled the medium to a perfection hardly seen before. At its most gestural and reductive, in studies of skies, clouds and waves it has contributed to modernist interpretations of Turner’s art (fig.27). But it is surely a mistake to argue, as did Kenneth Clark in 1969, that colour had taken on autonomous life for Turner, as the medium in which all form and feeling was subsumed;28 and that the essence of his art now rested in hidden and private rather than exhibited works.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Venice: Looking across the Lagoon at Sunset 1840

Watercolour on paper

244 x 304 mm

Tate D32162

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.26

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Venice: Looking across the Lagoon at Sunset 1840

Tate D32162

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Sunset c.1845

Watercolour on paper

240 x 315 mm

Tate D35990

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.27

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Sunset c.1845

Tate D35990

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

A Harpooned Whale 1845 from the Ambleteuse and Wimereux sketchbook

Graphite and watercolour on paper

238 x 336 mm

Tate D35391

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.28

Joseph Mallord William Turner

A Harpooned Whale 1845 from the Ambleteuse and Wimereux sketchbook

Tate D35391

Turner was well aware that his late watercolours were an acquired taste. From 1842 he used his agent Thomas Griffith to market Swiss subjects based on his summer travels. Very selectively, Griffith showed potential clients ‘sample studies’ developed from drawings originally made on the spot and, at first, some final versions to show them what commissioned versions would look like. The strategy was not wholly successful, winning fewer commissions and lower prices than Turner hoped, while some of the works shown were not immune from suspicions – even from Ruskin – of a ‘falling off’ in their handling. This was hardly the case in 1842, when Griffith presented the first batch of samples and four finished examples including The Blue Rigi – an epitome of Turner’s late watercolour at its most enraptured and inspired (figs.29, 30). Then as now, it was evident that the process from first impression to completed work could still pass through several stages, much as it had always done, even if the differences between the penultimate and last – other than in scale – were now subtle. Alongside the Bequest at Tate, The Blue Rigi has rejoined its sample study and also Turner’s first rough pencil sketch of the mountain, drawn in a sketchbook in 1802 from a boat on Lake Lucerne. Together they form a unique microcosm of Turner’s practice, and show the continuity as well as the radical transformations of style and technique that marked his progress as an artist working on paper over more than four decades.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Blue Rigi: Sample Study c.1841–2

Watercolour on paper

230 x 326 mm

Tate D36188

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.29

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Blue Rigi: Sample Study c.1841–2

Tate D36188

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Blue Rigi, Sunrise 1842

Watercolour on paper

support: 297 x 450 mm

Tate T12336

Purchased with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund (with a contribution from the Wolfson Foundation and including generous support from David and Susan Gradel, and from other members of the public through the Save the Blue Rigi appeal) Tate Members and other donors 2007

Fig.30

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Blue Rigi, Sunrise 1842

Tate T12336

E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (eds.), Library Edition: The Works of John Ruskin. Volume VII: Modern Painters: Volume V: Completing the Work, and Containing Parts VI Of Leaf Beauty–VII Of Cloud Beauty; VIII Of Ideas of Relation: 1. Of Invention Formal; IX Of Ideas of Relation: 2. Of Invention Spiritual, London 1903, pp.4–5.

Peter Bower, Turner’s Papers: A Study of the Manufacture, Selection and Use of his Drawing Papers 1787–1820, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1990, pp.39–43.

Andrew Wilton, ‘Sketchbooks’, in Evelyn Joll, Martin Butlin and Luke Herrmann eds., The Oxford Companion to J.M.W. Turner, Oxford 2001, p.297.

Greg Smith, The Emergence of the Professional Watercolourist: Contentions and Alliances in the Artistic Domain, 1760–1824, Aldershot 2002, p.86.

Kenneth Garlick and Angus Macintyre eds., The Diary of Joseph Farington [12 November 1798], vol.III, New Haven and London 1979, p.1090.

David Blayney Brown, ‘Stylistic Development in Oils and Watercolours’, in Oxford Companion, pp.311–15.

Wilton 2006, pp.25–6; Joyce Townsend, ‘Techniques in Oil and Watercolour’, in Oxford Companion, pp.329–30.

William Leighton Leitch, ‘The Early History of Turner’s Yorkshire Drawings’, Athenaeum, 1894, p.327.

Eric Shanes, Turner’s Watercolour Explorations, 1810–1842, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1997.

As recorded by Edith Mary Fawkes, typescript in the Library of the National Gallery, London; see also Robert Yardley, ‘First Rate Taking in Stores’, in Oxford Companion, pp.109–10.

Walter Thornbury, The Life of J.M.W. Turner, R.A., Founded on Letters and Papers Furnished by his Friends and Fellow Academicians, London 1877, p.87.

Note in a copy of Rogers’s Italy (Dyce Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, London); Luke Herrmann, Turner Prints: The Engraved Work of J.M.W. Turner, Oxford 1990, p.183.

Munro quoted by A.J. Finberg, The Life of J.M.W. Turner, R.A., Second Edition, Revised, with a Supplement by Hilda F. Finberg, Oxford 1961, p.360.

How to cite

David Blayney Brown, ‘Draughtsman and Watercolourist’, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www