Myriad Mediations: Henry Moore and his Works on Screen 1937–83

John Wyver

During his lifetime Moore and his works were seen frequently on television and in documentary films. From the 1950s onwards these appearances shaped a strikingly consistent and rarely challenged public persona as an artist concerned primarily with the ‘timeless’ subjects of the human figure and the landscape.

Only a very few visual artists in Britain have achieved the status of television celebrity. Since the late 1960s David Hockney has been one, and from the mid-1990s onwards Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and Grayson Perry have seen their celebrity in other contexts both partially created and mirrored by television. Before all of these, however, Henry Moore was most definitely a celebrity of the small screen and, from the early 1950s to the early 1980s, the dominant figure in television’s presentation of modern art. For the medium and its audiences Moore and his art proved acceptable and approachable. His sculptures and drawings were recognisably modern yet also grounded in tradition, in the human figure (especially the female body) and in the English landscape. The artist appeared happy to explain his work for the cameras, and it was his discourse, to the exclusion of almost all other analysis, that defined how his sculpture was received. Civic responsibility was typically represented as more important to him than sale prices, and artisanal skill (which he was happy to demonstrate) more central to his practice than any suggestion of an intellectual or ‘conceptual’ framework. This, in summary, is how Henry Moore was presented in the many television programmes, as well as documentary films, made until he died in 1986.

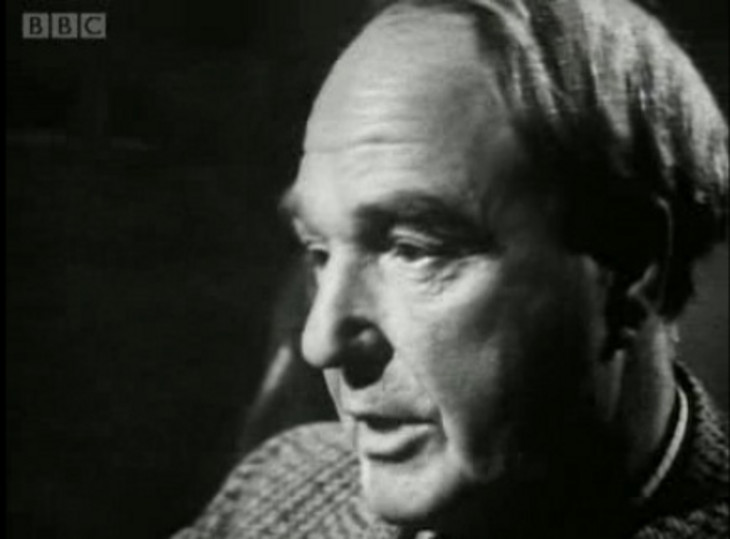

BBC publicity image of Henry Moore being filmed by John Read 1974

Fig.1

BBC publicity image of Henry Moore being filmed by John Read 1974

This essay looks at these and other television programmes and non-broadcast documentaries made by British producers during Moore’s lifetime, providing an initial overview of these myriad mediations and suggesting ways in which they can be understood. It aims to offer a basis for further critical engagement and analysis, made all the more timely as many of the films, including those made by the BBC, are becoming increasingly available.2 However, the essay is not intended to be comprehensive. Moore continued to engage filmmakers after his death, and a number of more critical studies have appeared in Britain including most notably England’s Henry Moore (1988) made by Antony Barnett and Hugh Brody. Moreover, while he was alive, Moore appeared in numerous news reports and documentaries made by filmmakers and broadcasters from abroad (in the extensive listing of copies of films held by the Henry Moore Foundation at Perry Green there are pre-1983 productions from the United States and Canada, and from Germany, France, Belgium, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal, Norway, Serbia, Bulgaria, Mexico, Singapore and Japan).3 Both the more recent films and the foreign productions, however, must be the focus for other articles.

The significance of still photography in the construction of Moore and readings of his works is well established (in 2001 Elizabeth Brown, for example, noted in a study of the centrality of photography to Moore’s working practices that, ‘investigating Henry Moore’s photographs promises a kind of direct access to the workings of his mind.’)4 The screen appearances of Moore and his work, however, have only the most minimal presence in the literature on the artist, even though, as John Read and others have confirmed, the sculptor influenced how his works were documented in moving images and these films played a determining role in shaping his public identity.5 Even texts that acknowledge the importance of films and televisions, along with newspapers and art journals, in constructing Moore’s persona typically focus on writing and still images, marginalising by exclusion the significance of television and films.6 Of course, this has been due in part to the difficulty of accessing historical films, lodged in film and television archives, but, as noted above, this situation is currently changing as more and more copyright owners are making the films available.

Moore’s first appearances on screen

The very earliest extant moving images of a work by Moore appear in a 1937 documentary titled BBC Television Demonstration Film. The BBC had begun a regular high definition television service from two studios at Alexandra Palace in north London in November 1936, and this documentary was a ‘survey of television production during the first six months of operation’, intended for viewing primarily by set manufacturers and engineers. The scenes were shot on film but otherwise closely mimicked the live electronic transmissions of the time. Included in the film is a sequence with the painter John Piper that lasts just over one minute and exemplifies the simplicity of early television’s presentation. Piper, who knew Moore well, stood in the studio with the sculptor’s elmwood Reclining Figure 1935–6 on a plinth flanked by easels on which are canvases by Gainsborough and Picasso. ‘I believe what sound broadcasting has done for music’, Piper said, ‘television may do for painting and sculpture. In the last few months I’ve been taking works from the London galleries to the Alexandra Palace and commenting on them and showing them.’ After brief observations about Gainsborough and Picasso, Piper turned to Moore’s figure and ran his finger along its back: ‘this is a carving by the young English sculptor Henry Moore. It’s a carving in wood. Moore is a Yorkshireman in his thirties and he has a rapidly rising reputation among artists and connoisseurs.’

One of Moore’s abstracted faces in stone also featured, alongside other modern ‘masks’ by Elise Passavant and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, in Masks through the Ages, a live televised talk by Duncan Melvin broadcast on 29 April 1937. Moore’s Composition 1932 (which, as discussed below, also appeared in Civilisation in 1969) was eulogised by the artist and author Wyndham Lewis in the television discussion Modern Art, broadcast on 23 May 1939. Lewis had the work in the studio and it was also reproduced in the Listener with a transcript of the exchanges with the poet and critic Geoffrey Grigson – like Lewis, on the side of modern art – and the Royal Academy’s painter A.K. Lawrence and architect Reginald Blomfield. About Composition Lewis enthused, ‘This particular piece is beautifully carved; and it displays an exquisite understanding of the problem of the object in space.’7 Reginald Blomfield, however, was unconvinced: ‘I don’t in the least understand what Mr Moore is after ... To me [his works] mean nothing at all.’

The first time that Henry Moore himself appeared on film was in a powerful sequence of just over four minutes in Jill Craigie’s documentary Out of Chaos (1944). This half-hour film, shot on 35mm and intended for cinema distribution, explored the work of a number of artists during the Second World War, and highlighted the activities of the War Artists Advisory Committee. It also looked forward to the role that visual artists might play in the reconstruction of Britain after the war.8 The sequence began with a generic newsreel shot of people wrapped in blankets on a tube platform as they shelter from the Luftwaffe’s bombing raids on London in 1940–1. The image cross-faded to a sequence reconstructed in a film studio at least two years later in which Moore picks his way down a crowded staircase into a beam of side lighting (which sets him apart from his subjects) and onto a platform packed with sleeping figures. Having introduced Moore, who was isolated in a heroic mid-shot gazing concernedly around him, Jill Craigie’s admiring narration said, ‘Here perhaps was the one artist capable of immortalising the stoic endurance and suffering of these people.’ Two sleeping women were shown before Moore wandered away to make a private note, shared with the camera, of what he had seen: ‘Remember Two Sleeping Women / mouths open / try to get restless feeling’.

The scene then moved to Moore working on a drawing in his studio at Perry Green, where the camera also picked up groups of maquettes and models. Of Moore’s drawings, Craigie said, ‘What really matters in his mind is that they should be timeless and elemental’. The only artist in the film granted the privilege of speaking about his work, Moore reflected on his process as he used first a wax crayon and then a watercolour wash to re-create a drawing of two sleeping women (Pink and Green Sleepers 1941, Tate NO5713). At the centre of this sequence, much of which was accompanied solely by a stirring romantic score by composer Lennox Berkeley, was an extended static shot that focused on the paper for sixty-five seconds as the drawing appeared through the wash. Forty years later Jill Craigie recalled: ‘Magically a powerful impression of two women restlessly asleep in the Underground appeared, the whole creating an atmosphere of oppression beyond the scope of a photograph. The execution of the work was so beautifully timed and adapted to a medium devised for action – it was shot in one take – that Henry’s conquest of the film unit was complete.’9 The sequence was an early example of what Philip Hayward identified in 1998 as the ‘extreme “fetishisation” of the actual moment of creation’ that became a common trope in films about the visual arts from the early 1950s onwards.10 The voice of the critic Eric Newton then described the image:

Deep shadows brood over the picture and out of the shadows emerge two heads sunk in an uneasy sleep. There’s no sharp detail to disturb them, only the mouths and nostrils of the sleepers stand out in relief, like symbols of the deep, slow-breathing of exhaustion. Yet it’s an unnatural sleep, troubled by memories of fear. It’s an oasis of tranquillity in the heart of a nightmare.

In Newton’s words there are strong traces of a complex understanding of Moore that was soon to disappear from films about the artist. Later documentaries valorised him above all as the supreme representative of an optimistic humanism grounded in ‘timeless’ English pastoral and figural traditions. After the war, and far from only in films, the Shelter Drawings came to be emblematic of the wartime survival of Britain and of the values that this triumph represented (as critic John Russell wrote in his obituary of the sculptor, the drawings transformed him into ‘someone who seemed to speak for a beleaguered nation in terms to which everyone could respond’).11 Yet Eric Newton’s compressed response in this film commentary suggests an artist whose work is shadowy, uneasy, unnatural, fearful and nightmarish.12

This dark and abject Henry Moore co-existed with the optimistic humanist in film of the immediate post-war years. The artist’s drawing Figure in a Shelter 1941 was employed as the background image for the opening titles of the Gothic-romantic horror film made by Ealing Studios, Dead of Night (1945), exemplifying the association of Moore with the uneasy and the uncanny (fig.2). Figures by Moore were also included in George Hoellering’s short film Shapes and Forms (1949), a film that was linked to the exhibition 40,000 Years of Modern Art, held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London and shown in the basement of Hoellering’s Academy Cinema. According to art historian Katerina Loukopoulou,

With only light and movement, [this film] draws on ‘pure’ cinema’s emphasis on visual rhythm and juxtaposition to convey the similarity of certain patterns across the centuries from ancient figures to Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon and Moore’s reclining figures. The film’s cinematography echoes German expressionism, with its dramatic shadows. The rotation of sculptures elicits engagement with three-dimensional artworks: in this way, the film presents an emphatic, modernist display of form.13

A ‘new model’ Moore was presented in John Read’s innovative documentary Henry Moore (1951). The son of the art critic and early champion of Moore, Herbert Read, John Read was a BBC producer who was charged with making a live television programme to mark the unveiling of a new work by Moore in the Festival of Britain and the artist’s first retrospective at the Tate Gallery. Read, however, was keen to produce a filmed documentary and with Moore’s support documented the artist at work in his studio in the Hertfordshire village of Perry Green. ‘Art is the expression of imagination and not the imitation of life’, Read’s script announced at the beginning of the film, and continued to attempt to explain Moore’s approach and the ideas fuelling his work. From this pioneering film emerged a sense of Moore as a humanist and English pastoralist, someone who had revived a tradition that had been ‘extinct in England for four hundred years, a tradition of expressiveness and truth to material’. The Festival of Britain commission provided the opportunity for the film to trace the development of the new work, from initial sketch to finished sculpture, and in so doing to appear to give television viewers privileged access to the workings of the artist’s mind.

In Henry Moore, as in all of his work, Read focused on a direct encounter with the artist. There are no critics or presenters in Read’s film, and each one aims for only minimal mediation by the camera. There are also moments where the screen simply shows an artist’s work, albeit with the viewer’s focus and feelings prompted by framing, camera movement and, often, by music. Here and in subsequent films with other artists –Graham Sutherland, John Piper, Barbara Hepworth and others – Read forged the framework and forms for television profiles of living artists. At the same time he expressed values and concerns that were rural rather than urban, individual rather mass-produced, organic and not technological, and modernist in the sense of offering a critique rather than an embrace of the modern material world. This was the understanding that he brought to and drew from Moore, and as expressed in the first film and the five that followed it was to prove immensely influential in framing the artist on screen. In 1960 an anonymous correspondent in the Times noted of John Read’s films about Moore, Sutherland and others that they ‘have done much to reconcile the most die-hard viewers to the modern artist’s way of seeing things.’14

In 1953 Read also featured several of Moore’s outdoor sculptures in his film Artists Must Live, made as a collaboration between the BBC and the Arts Council of Great Britain. This documentary explored the consequences for modern artists of the disappearance of private patrons and the difficulties of making a living from commercial gallery sales. Included are views of Henry Moore’s Madonna and Child 1943–4 in the parish church of St Matthew, Northampton, the Stevenage Family Group 1948–9 and the Time-Life Screen 1952–3. Artists Must Live used an even illumination, either employing or replicating diffused daylight, which became the default visual style for showing Moore’s works on film. In 1951 Moore’s work had also appeared in one of the series of films titled Painter and Poet. Produced by the animator John Halas with Joan Maude and Michael Warne for the British Film Institute, the series was conceived as ‘an experiment in words, music and paintings’. Each of the four films juxtaposed readings of poems with reproductions of paintings or drawings by a single artist and a contemporary score. The third film, with ominous modernist music by Matyas Seiber, included the poem ‘The Pythoness’ (1949) by Kathleen Raine. This was read by the actress Mary Morris against a selection of drawings by Moore that he had re-worked to strengthen the definition and clarity of the lines. ‘The Pythoness’ had an eerie, uncanny and strongly sexualised quality, and this brief sequence (it lasted little more than a minute) was effectively the final screen moment when a ‘Gothic Henry Moore’ made an appearance.

Television and the ‘Moore mythology’

The key tropes of television’s presentation of Moore and his works, which remained largely unchanged through to the sculptor’s death, were established in the decade following John Read’s Henry Moore. According to art historians Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell, a ‘Moore mythology’ was ‘put in place in several ways: by the worldwide presence of his work in galleries and institutions; in numerous accounts of Moore’s role in the formation of British and international modernism; through an interpretation of his work as representative of post-war humanism; and last, but not least, by Moore himself, aided by favoured critics, writers, photographers and curators.’15 News reports about Moore during the 1950s and 1960s helped cement the artist’s fame. A BBC News Review item shown on 28 May 1954, for example, included a view of Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3 in a feature about the Holland Park open air sculpture exhibition. Moore’s work also featured on the BBC television news on 17 May 1956 in a filmed report showing Sir Kenneth Clark unveiling Moore’s Harlow Family Group 1954–6. News coverage continued throughout his life, and included a 1962 Granada news item about him receiving the freedom of the Borough of Castleford, which featured the Roll of Honour Moore carved when he was at school there, and a BBC news item on 1 November 1967 about the unveiling of Knife Edge Two Piece 1962–5 in Parliament Square. Unlike news coverage of other modern sculptures, such as the furore in 1972 about the Tate Gallery’s purchase of Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII 1966 or ‘the bricks’, these reports maintained a respectful, often celebratory tone.

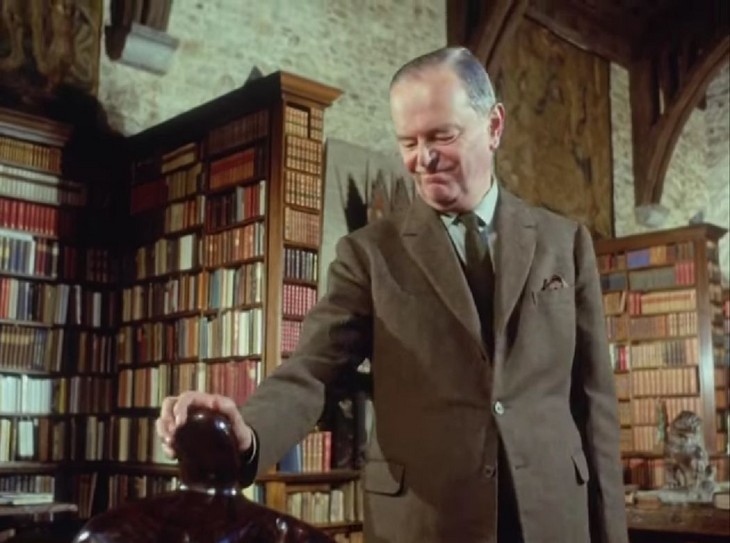

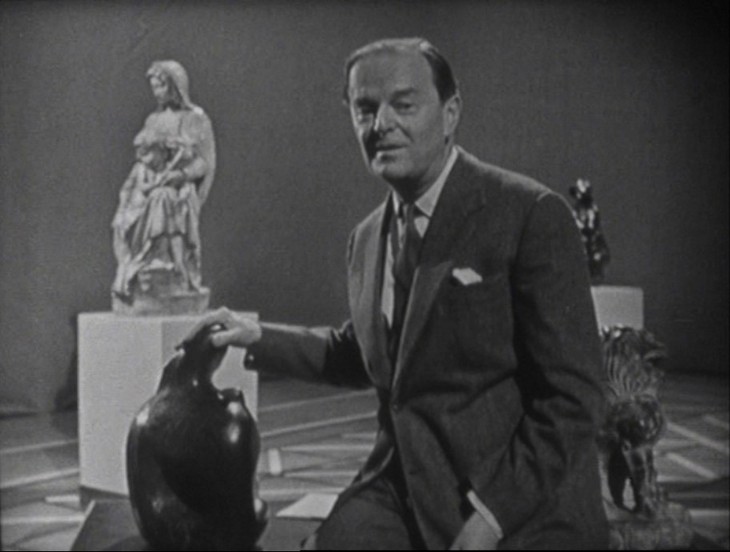

Still of What is Sculpture? (1959) showing Kenneth Clark touching Moore's Composition 1932

Fig.3

Still of What is Sculpture? (1959) showing Kenneth Clark touching Moore's Composition 1932

Still of Moore being interviewed in Face to Face 1960

Fig.4

Still of Moore being interviewed in Face to Face 1960

Broadcaster Huw Wheldon encountered a similar resistance later the same year when he, too, came to Perry Green to speak with Moore for the arts magazine series Monitor (1958–65), the BBC’s prestigious arts magazine series which was broadcast fortnightly on Sunday evenings.19 Expressing sentiments recorded frequently elsewhere, Moore commented, ‘I prefer really to not talk about one’s work too much, not to try to explain it too much. One can say things that don’t matter about it, yes, but to try to go into its deep motives and reasons are – I think stops, might stop, one from wanting to go on.’ But the artist underlined how he intended his work to be understood. ‘Sculpture,’ he said, ‘is purely this interest in form and shape. Not in literary ideas or that kind of thing.’ As in Face to Face, Mexican sculpture from centuries past was introduced to help ‘explain’ Moore’s work while references to contemporary art were excluded: the discussions placed Moore’s work within an elevated tradition of great art, and described it as motivated above all else by formal concerns.

As it exists in the archive, the twenty-minute Monitor film begins with a sequence lasting more than two minutes without narration (although this may have been added in the television studio for the broadcast), with a camera executing fluid movements around large-scale sculptures by Moore in one of his spaces at Perry Green. The music is lush with occasional traces of threat. The programme then cuts outside to a seated figure, framed against the sky but with a hand resting on its shoulder. As the hand – which is Moore’s – pulls away after caressing the figure’s back, there is another cut to Wheldon and Moore together walking out of shot. The sequence that follows establishes the extensive grounds of the estate, the comforting exterior of the former farmhouse Hoglands in Perry Green and its cosy interiors, in one of which a fire burns in the grate next to a television set. Yet the rooms are empty, apart from an anonymous woman seated with her back to us and a cleaning lady, and there are drawings and sculptures everywhere. ‘Moore himself doesn’t buy works of art,’ Wheldon’s commentary explains, ‘it’s Mrs Moore who does the collecting’, though later Henry Moore reflects on an oil sketch by the French post-impressionist painter Paul Cézanne he bought a year or so before.

Still from Monitor showing the interior of Moore's home 1960

Fig.5

Still from Monitor showing the interior of Moore's home 1960

The Monitor film constructed the artist as a country squire, with a solid house and rolling grounds, a modest domestic staff and a comfortable but not over-elaborate lifestyle. Nor, unlike in John Read’s 1951 and 1957 documentaries, did he appear in this film actually to do any work or engage in sculptural process or production. Indeed, such sequences hardly featured in any of the films beyond those made by Read, who continued to be granted privileged access. Like many later documentaries, the Monitor film reinforced what curator Jon Wood described as the ‘quasi-magical status’ of the studios at Perry Green where in accounts written later ‘each visitor can be read as having achieved some kind of unique and authentic experience and insight into the man and his work in its correct context.’21

Moore’s art in Monitor is domesticated (a drawing hangs above the bath, maquettes populate the window-sills) and the talk is civilised but middle-brow, with an occasional moment of humour. ‘I think I have a very romantic idea of women,” Moore says at one point, with a broad grin. There is an unspoken fear that the art might be seen as challenging by the programme’s audience, so its embedding in tradition is stressed, as is the continuity of its preoccupations with those of other great artists, known or anonymous, from five hundred years ago. Moore is shown to be accessible and appealing, especially when, in close-up, his hands explore the natural forms of a bone. Process and production, economy and history are all effaced, and the viewer is positioned as feeling privileged to have been granted this glimpse of the artist at home. This is a home, moreover, that, as Jon Wood wrote, ‘effectively symbolised Moore’s belief in the regenerative relationship between life and art’.22 At the time Monitor was the only primetime arts strand on either of the two television channels, and as a consequence was widely watched, even if individual editions of the series tended not to be reviewed. The film was repeated just under a year later (on 30 July 1961) and together with John Read’s documentaries in the 1950s, helped shape still familiar interpretations of Moore and his work.

The presentation, and self-presentation, of Henry Moore in Monitor and Face to Face, are striking records of the artist’s personality and considerable charm, which was noted by many of those who met him and which worked to disarm detailed critiques of his work. In 1946 A.M. Frankfurter wrote of the ‘deep pleasure of knowing the man himself – kind, sincere to a rare degree in a veiled society, alive with ideas and strength, undidactic, in short with all the seldom encountered marks of greatness’.23 How much more potent were these personal qualities when the viewer had a seemingly unmediated encounter with them, courtesy of the television screen? Notable, too, in both Face to Face and the Monitor film was the way in which Moore appeared to exist apart from, or indeed beyond, politics. Yet the 1950s and early 1960s were the years when Moore’s work in Britain was most deeply implicated in the processes of post-war recovery and reconstruction. Writing of the post-war Labour government, Margaret Garlake has detailed how an ‘unexpected relationship between social reconstruction and the visual arts emerged after 1946 in the form of several important patronage schemes ... The political reality of social reform had established the conditions for an expanded art support system, with higher educational standards, full employment and increased leisure contributed to the basis for a more widespread interest in the arts.’24 Shaped to a degree by this new context, to which television also contributed, Moore’s works of the 1950s, and perhaps especially the family groups, have been seen as symbols of a post-war return to order. The presentation of such works in the television programming of the time underscores this understanding of Moore through its placing of the works in a pastoral world of stability and tradition.

These interpretations obscured other aspects of Moore’s work and life. The programmes cited gave little time to coverage of the artist’s early professional life in the 1920s and 1930s or his engagement with various art movements. They also avoided mention of Moore’s experiences in the trenches of Flanders or discussion of the meanings that his works might have had to the generation after the First World War. Moore on screen, at least while he was alive, was an artist of the world after 1940, not the world after 1914. Such aspects only began to be explored by the medium in the major documentary England’s Henry Moore (1988), conceived by writer and commentator Anthony Barnett and directed by Hugh Brody. In an allusive and original film Barnett and Brody began with the traces in his work of Moore’s experiences on the battlefield and developed into an exploration of, as Barnett later wrote, ‘what it meant to be English, or at least working-class English ... Moore was part of something much larger than his military experience, however deeply traumatic. His great reclining figures are also metaphors for the immense power of perhaps the best-organised working class in the world. A movement that nonetheless knew its place and submitted to orders ... they have the strength but not the will to rise.’25

Beyond the small screen

Central as television was to the fashioning of Henry Moore for the post-war public in Britain, the artist and his works also appeared in films seen in contexts beyond the domestic screen. There were, for example, at least ten appearances between 1945 and 1969 of Moore and his works in British Pathé newsreels. These include ‘Fame in Fabric’ (1945) with Zika Ascher at the National Gallery looking at a Shelter drawing; ‘Open Air Sculpture’ (1960), which has a view of Moore’s Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross, 1955–6 at the Battersea Park open air sculpture exhibition; and ‘Henry Moore Receives Dutch Honour’ (1968), with the artist receiving the Erasmus Prize from Prince Bernhard and views of an exhibition at the Kröller-Müller museum in the Netherlands. As with television news coverage, the newsreels consistently treated Moore with respect and maintained a celebratory attitude.

Moore was also the focus of documentaries created for educational and other non-theatric forms of distribution. The British Council after 1955 made available a filmstrip of illustrations and a tape-recorded talk by Moore titled Sculpture in the Open Air. The main provider of cultural documentaries, however, was the Arts Council of Great Britain, which in the winter of 1950–1 organised the first ‘art films tour’. This offered a 16mm projector and operator, together with selections of films, to colleges and community organisations across Britain. Initially, these were prints of films purchased from abroad, and occasionally from the BBC (John Read’s Henry Moore was included in the 1951–2 tour). The Council then began to part-finance new productions, as it did in partnership with the British Council for Dudley Shaw Ashton’s Reclining Figure: Henry Moore’s Sculpture for the UNESCO Building in Paris (1959), with an adulatory commentary written and spoken by Philip Hendy, then Director of the National Gallery. Ashton’s film featured a number of the maquettes that Moore considered for this commission and travelled with the sculptor to the quarries at Carrara where the familiar comparison was made: ‘Here Michelangelo came to choose his marble.’ The conclusion celebrated the installed work with strong colour cinematography and a grand peroration from Hendy stressing the separation of Moore’s work from its inevitably politicised context of UNESCO’s headquarters:

While the typewriters click in the battery of office rooms behind the plate glass, and while men and women strive together in the conference rooms to raise themselves, and mankind with them, above the fears and doubts and pettiness of life, this Reclining Figure lies there, and there is watchful, courageous, empowered, a force on the side of greatness, a reminder of the grandeur to which the idea of humanity can reach.

Other organisations also created films for non-theatric distribution as 16mm prints. British Transport Films (BTF) produced numerous documentaries to promote railways and other forms of nationalised transport as well as their various destinations. In 1960 John Piper presented the BTF film An Artist Looks at Churches, in which Moore’s Madonna and Child 1943–4 features towards the close.26 Accompanying dramatically-lit images in colour of the Northampton work, Piper’s narration proposes that the sculpture, ‘draws out nineteen centuries of love from the stone where it has been hidden for that length of time and longer ... When our eyes are adjusted to these works of our own time [Graham Sutherland’s The Crucifixion 1946, also in Northampton, had been shown], they take their place naturally enough beside the treasures of the past.’ At which point an image of the Virgin’s face dissolved to a precisely aligned, worn visage of a medieval figure in stone. A montage of other faces, in stone, wood and stained glass gave way to pastoral shots of churches in the English landscape. As in the contemporary television films, Moore’s work was fixed reverently in a timeless pastoral tradition. Moreover, it was expressive of what art historian Andrew Causey identified as a ‘fervent Englishness’ and ‘essentialist nationalism’ that he saw as having been mobilised by the pre-war politician Stanley Baldwin. ‘This involved stressing the length and continuity of English history,’ Causey wrote in 2003, ‘the importance of land, the regions, craft and artisanal traditions, and social and class interaction.’27

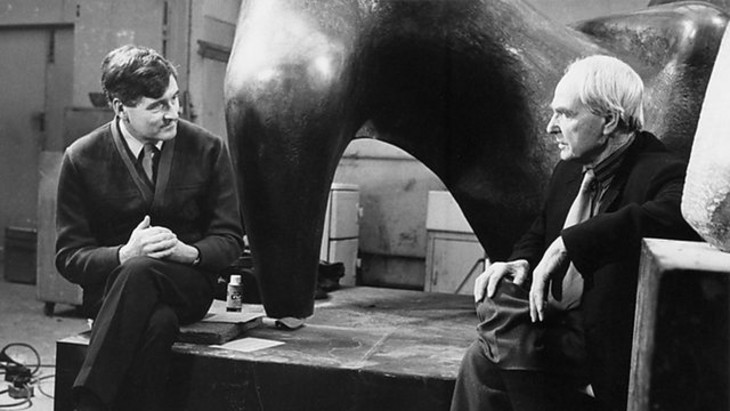

Films featuring the artist’s drawings and sculptures were also made for education, both by the broadcasters and occasionally by independent companies. In 1964 Anthony Roland Films produced the short Henry Moore, London 1940–1942, which focused on the Shelter drawings. Moore himself appeared in the documentary Figures in Space (which also featured the Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti) for the 1962 BBC Schools series Cubism and After, made by critic David Sylvester and television director Michael Gill, and in Fusion: Sculpture (Thames, 1971) directed by Richard Gilbert. Both schools programmes went to Perry Green to hear directly from the master, and the 1971 programme accompanied hand-held shots of works displayed in the grounds with an accompanying score of musique concrete.

David Sylvester was also central to the production of the Arts Council film Henry Moore at the Tate Gallery (1970). As a member of the Arts Council Films Panel at the time, he was involved in funding a number of films documenting major exhibitions. He was also the curator of the 1968 Henry Moore retrospective organised by the Council at the Tate Gallery, and the film of the show carries the credit ‘A film by Walter Lassally and David Sylvester’. Lassally was a great British cinematographer (his credits include The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) and Tom Jones (1963)), and the choreography of his fluid developing shots through the show remains impressive. The fourteen-minute film carries no commentary and no accompanying music, and simply records the display of Moore’s sculptures installed in Michael Brawne’s innovative exhibition design within the Duveen Galleries and (briefly) on the exterior lawn.28 To begin with the sculptures are seen in daylight, with visitors and the sounds they make in the spaces around the artworks. Then a dissolve between shots removes the people, and the camera – and viewer – is left alone with the works, with just a distant rumble from the city beyond. The camera in these later sequences grants the viewer privileged access to the show, at the same time as removing Moore’s work from the historical moment. Although the film acts in some ways as a catalogue for the exhibition, there are no captions to indicate titles or dates, nor is a chronology or other narrative apparent from the sequencing of shots.

One of the rare presentations of Moore that set his work in an explicitly contemporary context is Opus (1967),29 produced by James Archibald and directed by Don Levy for the Central Office of Information (COI). The film was commissioned to be shown at Expo 67 in Montreal, inside Basil Spence’s modernist British Pavilion, for the exterior of which Henry Moore loaned a cast of Locking Piece 1963–4. With no narration Opus is an impressionistic and freewheeling study of ‘the work of British artists, architects, composers, designers and sculptors’. After sequences, among others, featuring Eduardo Paolozzi, Centre Point, the GPO Tower, theatre and film productions by the Royal Shakespeare Company and artworks by Alan Davie, Francis Bacon, Reg Butler, Kenneth Armitage and Bridget Riley, the climactic ninety seconds, following the briefest of glimpses of Moore with a maquette, show Locking Piece and other sculptures. These are shrouded and veiled by branches in the landscape, with insistent focus-pulls discovering affinities between the creations and the natural world. By this point in the film, also, an early aggressively modernist score has changed to a romantic, strings-based accompaniment. Moore in Opus may be as of-the-moment as popular fashion designer Mary Quant, yet unlike that of all the other artists his work appears in this film as at home not in the city but in the country where it takes forms as seemingly timeless as the trees of England.

Responding to growing interest in Moore abroad, the COI made two further documentaries with the sculptor in the 1970s. Henry Moore (1976) celebrates the artist as a European figure, with a focus on the presentation of Three Piece Reclining Figure: Draped 1975 to the European Court of Justice. More interesting is the eightieth-birthday portrait of the artist made in 1978 for the COI series This Week in Britain. Although the film carries no credits, it was directed by Peter Greenaway, who was working for the COI at the same time as making his imaginative and often witty avant-garde shorts like A Walk Through H and Vertical Features Remake (both 1978). An unidentified female presenter explains that this is a ‘report on the sculptor from the contemporary point of view’. One of the supposedly vox pop interviews that are featured only in voice-over sets up the film’s questioning tone: ‘I feel that Henry Moore’s work was fairly relevant in the sixties, but at the moment I don’t think is terribly relevant, and in fact is a bit of a yawn.’ The modest irreverence also infects the images and editing, as details of Moore’s works are shown in fast-cut montages and with children using them as slides. There is the spoken suggestion, too, that ‘particularly with the bigger works, [Moore’s sculpture] tends to fall into a kind of empty rhetoric, rather like the speech of an international statesman’. The artist himself, however, is on hand to reassert is distinctiveness. ‘I don’t worry about the other sculptural directions now,’ he says. ‘My own direction is enough to last me, if I was given it, two or three other lifetimes.’ And at the end he once again compares himself with Michelangelo, and with Titian, in saying that neither of them retired towards the ends of their lives, and that he has no intention of doing so either.

Portraits of the artist as an older man

A decade before Peter Greenaway’s film for the COI, television had largely abandoned any criticality with regard to Moore. I Think in Shapes Not in Words (BBC, 1968) was directed by John Gibson at the time of the seventieth-birthday exhibition at the Tate Gallery, which also featured in the Arts Council film discussed above. This is a richly detailed interview with the artist who takes the viewer on a guided tour of the exhibition but without any challenge or questioning. And Moore disavows even the activity in which he is engaged when he states, ‘You can’t explain sculpture in words. Otherwise you’d write a poem or you’d write a book or a description and say, this is what I intended to do.’ The reverential attitude to the artist is maintained in a filmed interview, shot at his home, for the LWT series Aquarius for Christmas 1970 in which Moore described once again the genesis of the Northampton Madonna and Child. The sculptor sits with a maquette of the work, touching it all the time and speaking without the apparent intervention of an interviewer. Another short interview, filmed once more at his home, features in Christopher Burstall’s film for Omnibus, A Question of Feeling (BBC, 1973). Rare in that it features Moore alongside other living artists, including Bryan Neale, Kenneth Armitage and Barbara Hepworth, this documentary explores a range of ideas about sculpture. Yet the section with Moore is self-contained, and there is neither challenge to his ideas nor any explicit comparison with works by the other sculptors.

Curiously, research to date has not revealed any film or television news report during Moore’s lifetime that discusses the public renunciation of him, via a letter to the Times on 26 May 1967, signed by forty-one artists, including his former assistant Anthony Caro. Caro and others were concerned that a proposed gift by Moore of twenty or thirty important works to the Tate would not leave sufficient space, both physical and mental, for contemporary work that they believed at the time had more significance. This very public row had no place in any of the television programmes that were made after this. Rather, Moore continued to make uncontentious appearances in films like The Woven Image (BBC, 1980), written and presented by the critic Edwin Mullins, which featured an eight-minute section about tapestries made to Moore’s designs.

Four BBC films made between 1971 and 1980 considered aspects of the economy of Henry Moore, with the most pointed of them also presented by Edwin Mullins. Near the opening of Art at Any Price, 1: Art and Reputation (BBC, 1971), Mullins drives to Moore’s home in Perry Green to speak with the artist about reputation and reward. The artist is engagingly reticent, as he says, ‘I never think of success in the sense that other people may. It’s come so slowly.’ But left to wander through the studios, Mullins speaks to camera as he proprietorially touches a number of the sculptures: ‘He may be irrelevant to younger artists, which he is, but to most other people he’s Mr Modern Sculpture. He’s a living Old Master, and that’s that. He’s a court sculptor of the liberal establishment.’ Standing by a cast of Locking Piece, Mullins introduces the idea that there is something ‘quite new about reputations in contemporary art – they are heavily supported by business, by dealers.’ The film, however, then moves away from Moore and the specifics of the economics of his practice remain unexamined.

Arena: Art for Money’s Sake (BBC, 1976) looked at a number of aspects of the art market, and included an interview with Moore about dealers (‘useful but not essential’, he maintained) and what would happen to his works after his death. In the following year a short item for the early evening magazine show Nationwide (BBC) marked the establishment of the Henry Moore Foundation in Moore’s home and studio. And in her investigation Arts U.K. – O.K.? (BBC, 1980) the presenter Joan Bakewell slapped a late Moore bronze as she asserted that art, rather than being a drain on the public purse, was in fact a highly profitable industry. Moore’s works at Perry Green were used as the visual background for a number of Arts Council England figures making this economic case for the arts. In his interview, however, the artist distanced himself from this argument, saying, ‘The purpose of art is not making a living. For me the arts are to make people enjoy and appreciate the world much more than they might do without them.’

Reverence is the dominant tone, as is suggested by the title of the film The Majesty of Henry Moore (YTV, 1978), in which presenter Austin Mitchell visited an exhibition of Moore’s work at Cartwright Hall in Bradford. This appears to have been made as a multi-camera recording to videotape, and featured Moore rehearsing familiar answers to questions frequently asked before. In response, for example, to Mitchell’s query about why ‘a miner’s lad from Castleford’ became a sculptor, Moore said, ‘Well, why did Shakespeare become a playwright? Why did Michelangelo become a sculptor? I don’t know.’ Henry Moore: The Recollections of a Yorkshire Childhood (YTV, 1981) has a strongly nostalgic tone, while The Levin Interviews: Henry Moore (BBC, 1983),30 in which the artist was gently prompted by Bernard Levin, also covered familiar ground. The most engaging of these late interviews was that conducted for Henry Moore: Monumental Energy (Tyne Tees, 1984), in which the artist, who looked very frail, was still strikingly lucid. And in addition to these filmed elements, just before his death Henry Moore contributed a voice-over interview to Patron of Art: Walter Hussey 1909–1985 (BBC, 1985). In this recording Moore reflected on the challenge that the Madonna and Child commission represented to him back in 1942, and his battle for acceptance by the public at the time. The implication was that both artist and the British public have made a long, mutually productive journey across the previous forty years.

The art of others

As has already been suggested, right across the whole of the television and film record, Moore was presented as a modern artist sui generis. He never spoke about any other contemporary artists and programme makers rarely contextualised his work by comparisons with, for example, the sculpture of Barbara Hepworth or Anthony Caro. This was entirely consistent with the artist’s self-fashioning in other contexts. Dorothy Kosinski, for example, wrote of ‘Moore’s dissimulation’ about the impact of his near contemporaries, including Aristide Maillol, Constantin Brancusi, Arp, Jacob Epstein, and his teachers at the Royal Academy.31 There appears to be no reference in Moore’s filmed interviews to any of these figures. Critic Peter Fuller noted Moore’s ‘almost compulsive need to albate the memory of those artists who had a significant short-range influence upon him, preferring to admit to having learned only from the likes of Michelangelo and Masaccio.’32

When Moore spoke on film towards the end of his life about the art of others, he discussed only old masters, from Donatello to Rodin, with whom he implicitly aligned himself. In 1990, for example, the independent television arts series Aquarius produced the half-hour film Rodin at the Hayward (LWT, 1990). Directed by Derek Bailey, this featured sequences of Moore installing the Arts Council’s major Rodin exhibition with curators Alan Bowness and Gabriel White. In his introduction to the item presenter Humphrey Burton made explicit the commensurate eminence of the French sculptor and Moore: ‘We are privileged to show you some of Rodin’s work in the company of Henry Moore. And I mean privileged because the chance to hear one great sculptor’s views about another are rare indeed.’ In interview in the film Moore reinforced the affinity between himself and Rodin, and aligned the two of them with Michelangelo: ‘[Rodin] also learnt from Michelangelo the fact that the human body can express emotions that all of us feel, In fact it’s the most important thing in sculpture in the world, in my opinion, the whole of sculpture is based on this relationship and feeling ... It’s our body that we refer everything to.’ Moore also contributed to the short film Michelangelo’s Taddei Tondo (1972), directed by Susan Y. Legouix for Bath Academy of Art, and in a later short film for Aquarius, Moore on Michelangelo (LWT, 1975), the sculptor spoke about the Renaissance master in voice-over accompanying shots of Michelangelo’s works. The implicit judgement of the two artists as equals is secured when presenter Peter Hall wrapped up with the words, ‘A great artist talking about a great artist.’

The film Italian Breakthrough (BBC, 1978), directed by Kenneth Shepheard for the series Chronicle, featured Moore, filmed in his studio, speaking about Donatello. Here the alignment between past and present was clearest when Moore discussed one of his own drawings of a relief by Donatello. There was a similar sense of the sculptor as the peer of one of the greatest of all artists in the title of Henry Moore Meets Leonardo (BBC, 1978)33, an eight-minute interview directed by Nigel Finch and illustrated with rostrum-shot images of Leonardo’s anatomical drawings. Italian Breakthrough also included one of the most moving of all of Moore’s statements of his humanist beliefs, when he ranked Donatello as the equal of Leonardo, Michelangelo, Rembrandt and Titian: ‘What relates all of the people I’m talking about is their great humanity – the fact that they love life, understand the tragedies and miseries and so on, but give to other people this engagement and belief that life is a wonderful thing, worth living.’

On two other occasions Moore gave filmed interviews about the two post-impressionist painters that he most admired. In Point Counterpoint: the Life and Work of George Seurat, 1859–1891 (BBC, 1979), directed by David Thompson, he related the works of the French painter to his own wartime coal mine drawings. And in the earlier Cézanne (BBC, 1973), directed by Margaret McCall, Moore reflected that encountering Cézanne’s Les Grandes Baigneuses was ‘like seeing Chartres for the first time’. Here too, however, he spoke of how he and Cézanne share the same ideal: ‘One aims at something, not a vague idea of beauty, which after all you can’t define. You’re aiming at some further understanding of reality.’

Touching Henry Moore

In the very first appearance of a Moore work, a reclining figure, on the screen in 1937, the painter John Piper ran a finger down its back. Piper was the first of many commentators to touch a Henry Moore sculpture on film. Over and over, reporters and commentators, as well as the artist himself, reach out to, caress and slap the works, to stress their solidity and their materiality. The 1968 BBC film I Think In Shapes Not Words, for example, concluded with Moore leaning on one of his works, then caressing it, rubbing his hands on its curves and then knocking it. In Fusion: Sculpture, a film for schools made by Thames Television in 1971, the presenter John Parry made explicit his desire for a haptic experience of the work. Standing with Two Piece Reclining Figure No.1 1959 in the grounds of Moore’s home, he says, ‘Walking around [the sculpture], I felt instinctively that I wanted to touch it, to run my hand over its surfaces. There’s something about his work that just makes you want to feel involved with it.’

Touching Moore’s works on camera, and especially the caressing and slapping of the large bronzes, realised a fantasy that can be identified in the writings of many commentators on his work, as Elizabeth Brown recognised:

Moore’s later figures possess a vivid sensory charge. The sculptures are intensely tactile: countless writers talk about touching the figures, feeling their textures, establishing a haptic connection. Overwhelmingly Moore’s subject is the supine female body, its fecundity either implicit in its mounds and hollows or explicit in the form of a child accessory. His photographs promote precisely this equalised reading by caressing, nudging and even penetrating the figures.34

The films that show this – and almost all of those mentioned in this essay include an example – echoed Moore’s own hapticity as he touched not only his sculptures but also the pebbles and bones that he used time and again to ‘explain’ his ideas. And for the commentators, this obsessive touching appeared to underline a sense of authenticity in the works, and in their experience of them.

Two of the most significant acts of touching a Henry Moore on film come in significant sequences in the two foundational series made for the BBC about the sciences and about the arts, The Ascent of Man (1973) and the precursor that inspired it, Civilisation (1969). Towards the end of episode three of The Ascent of Man, titled The Grain in the Stone and directed by Mick Jackson, presenter Jacob Bronowski made the seemingly obligatory comparison between Moore and Michelangelo, which Moore himself underlined by saying, ‘I had to think in the same way that Michelangelo did’. Bronowski then stood in the grounds of Moore’s home next to an example of Knife Edge Two Piece 1962–5, which he touched as he said, ‘The world can only be grasped by action, not by contemplation. The hand is more important than the eye’. In a lengthy developing shot that followed Bronowski walking around the monumental piece, the presenter grasped the sculpture and hit it several times to underline the significance of the episode’s peroration. ‘Civilisation is not a collection of finished artefacts’, he asserted. ‘It is the elaboration of processes. In the end the march of man is the refinement of the hand in action.’ Cut to a close-up of Bronowski’s hand once again hitting the sculpture, before choral music swelled on the soundtrack with a montage of various hands engaged in a variety of tasks.

In Civilisation Sir Kenneth Clark was rather less demonstrative when he featured Moore’s Composition 1932, which he owned, at the conclusion of the final episode of the series. This was at least the third appearance of the sculpture on television, following its inclusion in the 1939 Modern Art broadcast and What is Sculpture? in 1959. Addressing the camera about his fears for the future, Clark said, ‘One may be optimistic, but one can’t exactly be joyful at the prospect before us.’ He stands and walks through the library of his home at Saltwood Castle. In the final shot he came towards the camera past a table on which Composition sat and, with measured casualness, he lightly caressed its head (fig.6). Clark passed out of shot, the camera reframed slightly to position the sculpture more centrally, and the lighting on the work was brought up before the shot cross-faded to the closing titles. Clark saw Moore work as a talisman of hope in a bleak world threatened by new barbarisms. In the act of touching it he treated it as a charm with quasi-mystical powers, while at the same time affirming his tentative belief in the survival of the values of civilisation that he had explored in the thirteen films. For Clark, as with Bronowski who used precisely the same word, Moore’s work at that moment was a supreme expression of civilisation. Both men demonstrated their commitment to this abstract ideal not only with their words nor with the images the camera could achieve, but with the sense that their chosen medium of television denied – touch.

For almost fifty years Henry Moore was the modern artist who appeared more than any other in British television and films. The post-war Moore featured on the small screen in the post-war years was an accessible and unthreatening liberal humanist, who appeared to be concerned with the same problems as Michelangelo and Rodin and to tackle them with a comparable facility. He was presented as if beyond history and politics, desexualised and made familiar by constant stock comparisons, whether with him and Michelangelo or his sculptures with bones and stones. This was the man and this the work that embodied contemporary civilisation, it was suggested, and television was the new medium to show and to tell people that this was indeed the case.

Notes

A fragment of Moore at work even appeared in a spoof of the title sequence for the sports magazine series Grandstand in the Monty Python’s Flying Circus sketch ‘It’s the Arts’ (1969).

A selection of the BBC archive films with Moore can be found at ‘Henry Moore at the BBC, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/ , accessed 14 September 2014.

A typewritten ‘internal working list’ of digitised copies of films with and about Moore is regularly updated by the Henry Moore Foundation. I am immensely grateful to Michael Phipps, Martin Davis and Joanna Hill at the Foundation for access to viewing copies and for all their assistance in the research for this article.

Elizabeth Brown, ‘Moore Looking: Photography and the Presentation of Sculpture’, in Dorothy Kosinski (ed), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, Dallas Museum of Art/New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001, p. 287. See also Marin Sullivan, ‘Moore’s Photographic Identity’, Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity 2015 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/marin-sullivan-moores-photographic-identity-r1151299 , accessed 10 September 2015.

The writing of Katerina Loukopoulou about early British films on the arts is an important exception (see Katerina Loukopoulou, ‘A Cultural History of Films on Art in Post-war Britain’, unpublished PhD. thesis, Birkbeck, University of London 2010).

An example is Pauline Rose’s Henry Moore in America: Art, Business and the Special Relationship (2014) where she noted how ‘the man and his work [were] presented as refined, dignified and honest’ across newspapers, art journals and documentaries and that ‘still photography and film played a significant role in promoting and defining Moore’ (p.11), but focused on textual sources and images in her analysis of the construction of Moore’s persona in America.

In addition to showing Henry Moore, the film included an interview with Sir Kenneth Clark and sequences shot on location with Anthony Gross, Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash and Graham Sutherland, none of whom was interviewed.

Philip Hayward, ‘Introduction: Representing Representations’, in Philip Hayward (ed.), Picture This: Media Representations of Visual Art and Artists, Luton, second edition 1998, p.7.

In 2010 art historian David Mellor characterised Moore’s wartime drawings as depictions ‘of imaginary and actual elemental spaces that were claustral and uncanny, composing an Existential panorama of corporeal deprivation, fortitude and oppression ... a mix of representationalist figuration and a Gothic invocation of the London dead.’ David Alan Mellor, ‘”And oh! the stench”’: Spain, the Blitz, Abjection and the Shelter Drawings, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, p.52.

Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell, ‘Introduction’ in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, pp.2–20.

For the series and Kenneth Clark’s other work for ATV, see John Wyver, ‘Television’, in Chris Stephens and John-Paul Stonard (eds.), Kenneth Clark: Looking for Civilisation, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2014, pp.123–31.

The programme is available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8803.shtml , accessed 14 September 2014.

The programme is available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8804.shtml , accessed 14 September 2014.

Penelope Curtis and Fiona Russell, ‘Henry Moore and the Post-War British Landscape: Monuments Ancient and Modern’, in Beckett and Russell (eds.) 2003, p.140.

Jon Wood, ‘A Household Name: Henry Moore’s Studio-Homes and their Bearings, 1926–46’, in Beckett and Russell (eds.) 2003, p.20.

A.M. Frankfurter, ‘America’s First View of England’s First Sculptor’, Art News, December 1946, p.26.

Margaret Garlake, New Art, New World: British Art in Postwar Society, New Haven and London 1998, p.8.

Anthony Barnett, ‘England’s Henry Moore: The Sculptures of “the greatest Englishman”’, OurKingdom website, 23 April 2010, https://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/anthony-barnett/moore-of-england-modern-sculpture-and-englands-20th-century , accessed 26 October 2014.

The thirteen-minute film, directed by John Taylor, is included in the BFI DVD release, British Transport Films Collection, Volume Five: Off the Beaten Track.

For a discussion of the exhibition design, see Christopher R. Marshall, ‘“The Finest Sculpture Gallery in the World!”: The Rise and Fall –and Rise Again – of the Duveen Sculpture Galleries at Tate Britain’, in Christopher R. Marshall (ed.), Sculpture and the Museum, London 2011, pp.186–7.

The twenty-seven-minute film is included in the BFI DVD release COI Collection, Volume Five: Portrait of a People.

The programme is available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8817.shtml , accessed 14 September 2014.

Peter Fuller, ‘Henry Moore, An English Romantic’, in Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1988, p.39.

The programme is available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8812.shtml , accessed 14 September 2014.

John Wyver is Senior Research Fellow at the University of Westminster and a media producer.

How to cite

John Wyver, ‘Myriad Mediations: Henry Moore and his Works on Screen 1937–83’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www