London Narratives in Photography 1900–35

Valerie Williams

Photography was already well established by the time the Camden Town Group was formed, but Valerie Williams describes photographic representations of London in the 1910s as ‘unconfident and fragmented’. It would not be until the 1930s that photographers began to explore the narratives and domestic scenes found in the Camden Town Group’s interpretations of London life.

Well into its creative and technical stride by 1910, British photography was remarkable for its multiplicity and variability. In portraiture, landscape and record-making, its output was notable. The photographs of, for example, Julia Margaret Cameron, William Henry Fox Talbot and P.H. Emerson have become the enduring representations of Britain and British life in the nineteenth century. But in picturing the metropolis it was reticent. When the window of photography does open, and London is exposed, then the images we see are arresting. But until the arrival and take-up in the early 1930s of small-scale, portable cameras (such as the 35mm Leica) and the subsequent development of photojournalism, our view of London is fragmented and obscure. The intimate studies of London and Londoners presented by émigré photographer Bill Brandt in his 1935 book The English at Home, or the richly peopled narratives made by Picture Post photographers such as Bert Hardy and Kurt Hutton in the 1940s, provide the first vivid ‘interior’ and intimate studies of London life in photographs.

Those interested in photography’s ability to capture the fleeting moments and gestures that would contribute to the telling of London’s story would have to wait another two decades to see the detail which the Camden Town Group and its associates had been portraying in paint earlier in the century in such works as Charles Ginner’s The Café Royal 1911 (Tate N05050, fig.1) and Walter Sickert’s The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian 1915–16 (Tate N05288, fig.2). During the years in which photography still struggled to overcome not only the limits set by its emergent technology but also the strident views of a pictorialist establishment, the medium had yet to take its place as the primary documenter of ‘real life’. Though much personal, family and commercial photography (which, in its own way, could tell an equally compelling story of London life) emerged from the end of the nineteenth century, especially after the introduction of the first Kodak box camera in the late 1880s, amateur photography was simply not able to provide the compelling visions of the city which we associate with either primary artist photographers or technically and artistically adept studio practitioners.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Café Royal 1911

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 483 mm; frame: 878 x 725 x 100 mm

Tate N05050

Presented by Edward Le Bas 1939

© Tate

Fig.1

Charles Ginner

The Café Royal 1911

Tate N05050

© Tate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian 1915–16

Oil paint on canvas

support: 254 x 356 mm; frame: 421 x 513 x 88 mm

Tate N05288

Purchased 1941

© Tate

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian 1915–16

Tate N05288

© Tate

Given these limitations and accepting that photography’s position as image-maker was still a tenuous one, London was nevertheless extensively photographed at this time. The emergence and popularity of studio portraiture throughout London resulted in a great surge of photographic portraits. Consequently, we can see what Londoners looked like, the clothes that they wore, glimpse aspirations and observe an engagement with the photographic process. The collecting of mass-produced carte de visite (small photographs mounted on card) and cabinet portraits (larger versions of carte de visite) of actors, dancers and music hall artistes, as well as royalty and socialites, reveals an appreciation of London’s position as a centre of cultural activity and celebrity, which photographers would continue to describe.

Alvin Langdon Coburn 1882–1966

Leicester Square, London c.1909

Photogravure

200 x 145 mm

National Media Museum

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

Photo © National Media Museum / Science and Society Picture Library

Fig.3

Alvin Langdon Coburn

Leicester Square, London c.1909

National Media Museum

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

Photo © National Media Museum / Science and Society Picture Library

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Leicester Square 1912

Oil paint on canvas

642 x 559 mm

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Fig.4

Charles Ginner

Leicester Square 1912

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

One individual who did photograph London in these early years was the American Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882–1966), whose pictorialist representations of the city have remained enduring images of the metropolis as a place of rich shadows and urban mystery. Photographing Leicester Square in 1909 (fig.3), Coburn saw a city tinged with both melancholy and glamour, with theatre lights glimmering through the slick of rain. In contrast, Ginner painted Leicester Square three years later in the daytime with vivid colours and fine detail (fig.4). In 1905 Coburn had made a photograph of St Paul’s Cathedral, photographed from Ludgate Circus.1 Caught in a billow of steam, this workaday city suddenly seems a phantom, wreathed in atmosphere. Coburn’s London photographs are wraithlike, almost detached from the clamour and flux of the city.

Although an intimate portrait of London life would only appear with the advent of photo-documentary and reportage in the 1930s, early photography had proved itself to be of significant value in documenting important events and official gatherings. The Great Exhibition of 1851 was documented in the Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue, consisting of eleven volumes illustrated by calotypes by Nikolas Henneman, C.M. Ferrier and Hugh Owen.2 In this set of photographs, industry, innovation and an intense sense of the global were all identified as central to the photographers’ imaginations. Philip Henry Delemott’s photograph The Opening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham on the 10th of June, 1854,3 captured the magnitude of this spectacular event. Although this material may seem to fall outside the scope of the period which is considered here, photographers of the 1920s and 1930s would have been acutely aware of their heritage, even if only to challenge it.

Christina Broom 1862–1939

Christabel Pankhurst at the International Suffragette Fair, Chelsea 1912

Modern gelatin silver print from original negative

254 x 305 mm

Museum of London

Photo © Museum of London

Fig.5

Christina Broom

Christabel Pankhurst at the International Suffragette Fair, Chelsea 1912

Museum of London

Photo © Museum of London

If the intimate narrative photograph of London was yet to emerge, then it might be supposed that the metropolis might have emerged, through photography, as an iconic city. But here, too, at the beginning of the twentieth century, photography’s picturing of London is unconfident and fragmented. The vigour that British photography had demonstrated in the nineteenth century had dissipated as the schism between ‘commercial’ and ‘art’ photography deepened. No one photographed London in the ways that Paul Strand and Alfred Stieglitz had New York or Eugene Atget had Paris. New York, the epicentre of new ways of photographic seeing and thinking, encouraged photographers to explore the meanings of space and place, illustrated so clearly by Paul Strand’s 1915 photograph of Wall Street,4 and Stieglitz’s From the Back Window at ‘291’ 1915.5 Meanwhile, in Paris from 1900–25 Atget was producing a narrative of the city which expressed intimacy and a delight in the ordinary.

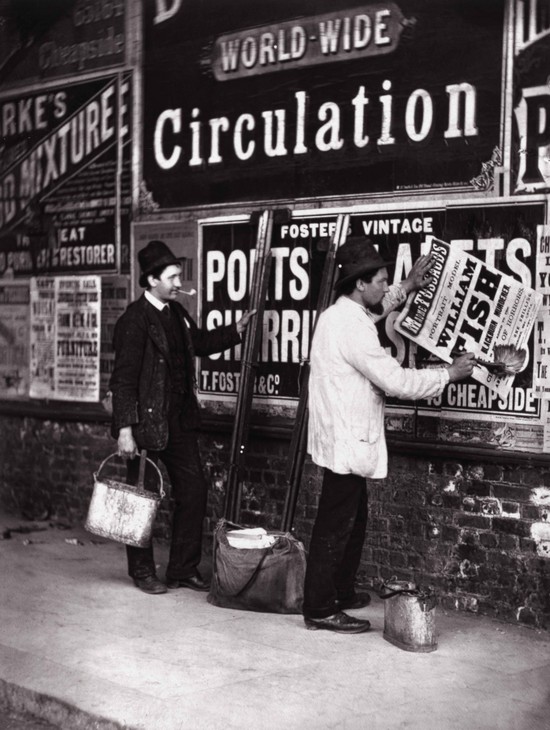

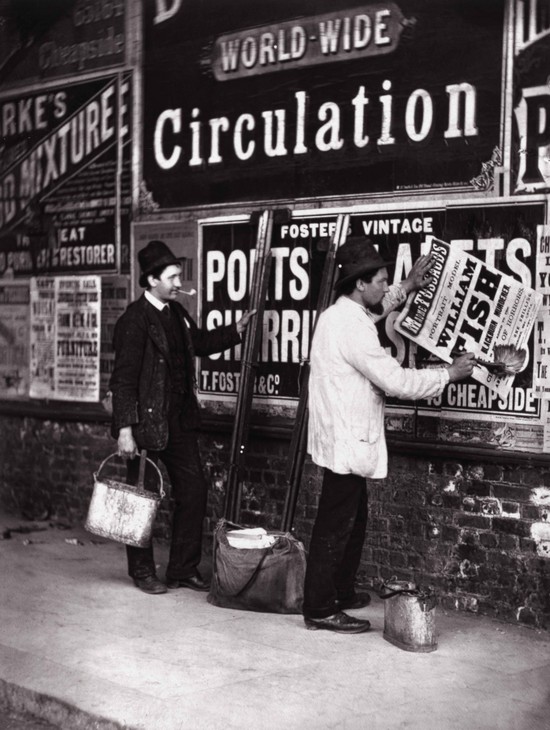

Sporadically, however, London was photographed in a way that proved that purposeful documentary narrative could be applied to the city. In the late nineteenth century John Thomson’s series of photographs, Street Life in London 1878 (figs.6, 7 and 8), was a deliberate attempt to record the city and its inhabitants.6 That he made photographs as a newcomer to London, after a lengthy time spent abroad, is perhaps significant. Thomson saw the city with an outsider’s eye, as an observer of otherness.

John Thomson (1837–1922) – whose partnership with the writer Adolphe Smith produced a vision of London echoing that of the writer Henry Mayhew’s collection of articles London Labour and the London Poor (1851)7 – had recently returned from extensive travels in Malaya, Sumatra, China and Cambodia and had operated a photographic studio in Singapore. Resident in London from 1872 after this ten-year sojourn abroad, Thomson brought to his photographs of London the ethnographic methods which he had employed in his photographic expeditions overseas.

John Thomson (1837–1922) – whose partnership with the writer Adolphe Smith produced a vision of London echoing that of the writer Henry Mayhew’s collection of articles London Labour and the London Poor (1851)7 – had recently returned from extensive travels in Malaya, Sumatra, China and Cambodia and had operated a photographic studio in Singapore. Resident in London from 1872 after this ten-year sojourn abroad, Thomson brought to his photographs of London the ethnographic methods which he had employed in his photographic expeditions overseas.

John Thomson 1837–1921

London Cabmen, from 'Street Life in London' 1877–8

Photograph, Woodburytype

113 x 89 mm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.6

John Thomson

London Cabmen, from 'Street Life in London' 1877–8

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

John Thomson 1837–1921

Covent Garden Flower Women, from 'Street Life in London' 1877–8

Photograph, Woodburytype

109 x 84 mm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.7

John Thomson

Covent Garden Flower Women, from 'Street Life in London' 1877–8

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

John Thomson 1837–1921

Street Advertising, from 'Street Life in London' 1877–8

Photograph, Woodburytype

110 x 90 mm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.8

John Thomson

Street Advertising, from 'Street Life in London' 1877–8

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Though Street Life in London contained photographs which shaped the imaginations of many who were to develop reportage and photo-journalism in London throughout the twentieth century, and gives a significant insight into the lives of London’s poor and working people in the nineteenth century, there is little indication that photographers were used to document the social conditions of London’s poor in any systematic way. Compare this to the position of documentary photography in the United States, where, as Peter Szto has described in a 2008 article,8 Lewis Hine produced social documentary photographs for the National Child Labor Committee and worked as a staff photographer for ‘Charities and the Commons’ from 1908. Such documentation which did occur in London or elsewhere in Britain was sporadic, individualistic and driven by the aim and politics of individual photographers and their collaborators.

When Norah Smyth (1874–1962) photographed the mothers and children who were being assisted by the East London Federation of Suffragettes in Bow, her images, mostly dating from 1914–15, and hidden in archives for many years, were taken to advertise the work of the ELFS, to demonstrate philanthropy and partnership in the organisation of day nurseries, small-scale factories and canteens.9 Smyth was not a professional photographer and her practice was influenced neither by the art photography debate nor by a commercial imperative. Its sole purpose was to propagandise the ELFS cause. Intimate and sympathetic, Smyth’s photographs are a rare early twentieth-century London narrative.

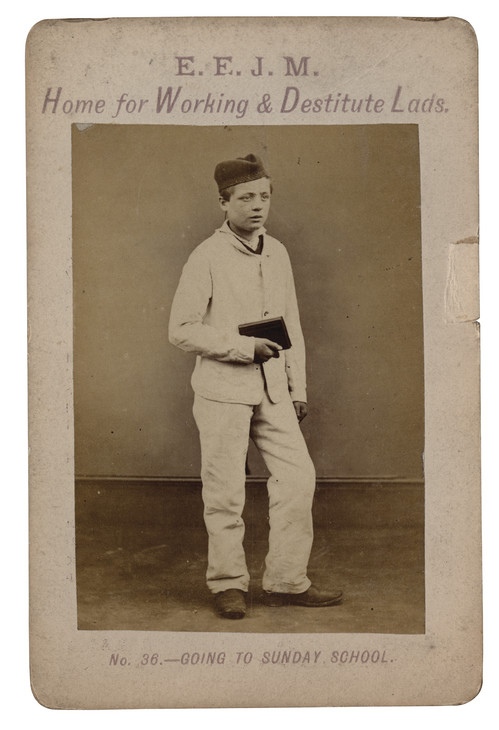

Thomas John Barnes

Barnardo Before and After Picture c.1872

Albumen silver print cabinet cards

81 x 57 mm

Barnardo's Photographic Archive

Photo © Barnardo's Photographic Archive

Fig.9

Thomas John Barnes

Barnardo Before and After Picture c.1872

Barnardo's Photographic Archive

Photo © Barnardo's Photographic Archive

Thomas John Barnes

Barnardo Before and After Picture c.1872

Albumen silver print cabinet cards

81 x 57 mm

Barnardo's Photographic Archive

Photo © Barnardo's Photographic Archive

Fig.10

Thomas John Barnes

Barnardo Before and After Picture c.1872

Barnardo's Photographic Archive

Photo © Barnardo's Photographic Archive

Inevitably, given its ascendance in London in the early years of the century, it is studio photography which provides the greatest insight into London life of the period. The philanthropist Dr Barnardo (1845–1905) employed studio photographer Thomas John Barnes to make ‘before and after’ photographs of ‘destitute lads’ whom Barnardo had found in the poorest districts of London and who were then trained in various trades (figs.9 and 10). Photographing the children first in rags and then in tidy workmen’s clothes, Barnardo and his collaborator created a performed narrative of destitution and improvement in the early 1870s.

Far less noble in his aims was the solicitor, poet, amateur photographer and ‘collector’ of working women, Arthur Mumby (1828–1910). Though many of the photographs that Mumby commissioned, from a wide variety of studio photographers, were taken in the northern industrial areas of Britain, a number, including those of Hannah Cullwick, the servant whom he secretly married, were made in London.10 For Mumby, working women meant dirty women and, preserved in his diaries (1858–98) and in Hannah Cullwick’s journal (now housed at Trinity College, Cambridge), are accounts of the process of identifying subjects, dirtying them up and then photographing them. Barnardo, Mumby and their proxy studio photographers made ‘slum narratives’ in the second half of the nineteenth century, which, as different in intention as they were, exemplified the fascination for the mysterious and deprived ‘other’ London, which was shared by so many.11 Cultural geographer Gillian Rose’s notion of the feminised space, which she argues emerged in 1930s London, and which began a reconfiguration of documentary photography,12 could not be better proved than by examining the twin and yet polarised figures of Barnardo and Mumby, who used the spaces of London photographic studios to express their hopes and desires.

Rose has suggested that London’s East End was photographed as interior rather than exterior space only from the 1930s in part because technical innovation enabled a different, more intimate kind of photography, but also because photographers began to see themselves as social campaigners using photography to illustrate and expose the housing conditions that many Londoners endured.13 If John Thomson saw his photographs of London street life in the late nineteenth century as a fascinating exercise in ethnography, the émigré documentarist Edith Tudor-Hart (1908–1973), photographing north London working women and their children in the 1930s, saw her work as an instrument of social change and public education.14

The photographs of London in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries both reflect the city’s character – the dizzying contrasts between the opulent and the decayed, the immense multiplicity of occupation and habitat, and the modern attempting to colonise the old – and photography itself, which, lacking the dominant master photographers of New York, did not have an overarching identity. It is a remarkable variety of opinions and observations about place and people that photographers – including Paul Martin, John Thompson, Norah Smyth and later Bill Brandt, Cecil Beaton, Margaret Monck and Edith Tudor-Hart – used to make documents which have endured as idiosyncratic chronicles of a city whose identity was already forged through the writings of Charles Dickens, Arthur Morrison, Arthur Conan Doyle and Jack London and the paintings by artists such as the Camden Town Group.

As Kevin R. Swafford has observed in a 2006 article, nineteenth-century London became a central focus for writers and social commentators who saw themselves as ‘explorers’ or ‘conscientious adventurer[s]’,15 epitomised by Arthur Morrison’s A Child of the Jago (1896) and Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor. Though some photographers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were also active in the telling of London’s story as it related to the social conditions and lives of the working and unemployed poor, this narrative, so central to photography in its later history, would remain substantially untold until the emergence of photojournalism and campaigning social documentary photography in the early 1930s. With this, London finally emerged as a focus for a complex and many layered photographic practice, demonstrated in the work of photographers such as Humphrey Spender, Bert Hardy, Kurt Hutton, Wolf Suschitsky, James Jarche and many more. Through the work of these photographers London’s visual identity as a place of serious spectacle became, and remains, firmly established.

Notes

Reproduced at http://www.leegallery.com/photographers/71-alvin-langdon-coburn.html , accessed October 2010.

Reproduced in Val Williams and Susan Bright (eds.), How We Are: Photographing Britain from the 1840s to the Present, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2007 (31).

In the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/73744.html?mulR=31908 , accessed October 2010.

In the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, http://www.moma.org/collection/object.php?object_id=83914 , accessed October 2010.

A selection of the photographs is reproduced at http://www.vam.ac.uk/images/image/41144-popup.html , accessed October 2010.

Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor can be found at http://www.archive.org/ , accessed October 2010.

Peter Szto, ‘Documentary Photography in American Social Welfare History 1897–1943’, Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, vol.35, no.2, June 2008, pp.91–110.

For further information on Smyth, see Val Williams, ‘No Cockneys in the East End: Women Documentary Photographers 1900–1918’, The Other Observers: Women Photographers in Britain 1900 to the Present, Virago, London 1986, pp.25–46.

Kevin R. Swafford, ‘Resounding the Abyss: The Politics of Narration in Jack London’s The People of the Abyss’, The Journal of Popular Culture, vol.39, no.5, 2006, pp.838–60.

Gillian Rose, ‘Engendering the Slum: Photography in East London in the 1930s’, Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, vol.4, no.3, November 1997, pp.277–300.

Valerie Williams is Professor of the History and Culture of Photography and Director of Photography and the Archive Research Centre at London College of Communication, University of the Arts London.

How to cite

Valerie Williams, ‘London Narratives in Photography 1900–35’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www