Walter Sickert: ‘The naked and the Nude’

Barnaby Wright

In an article of 1910 Walter Sickert famously condemned the highly artificial nature of the nude championed by academic painting. Barnaby Wright explores Sickert’s efforts to reinvent the nude through his controversial paintings of women in ordinary bedroom settings.

The modern flood of representations of the vacuous images dignified by the name of the Nude, represents an intellectual bankruptcy that cannot but be considered degrading, even by those who do not believe the treatment of the naked human figure reprehensible on moral or religious grounds.1

In his 1910 article ‘The naked and the Nude’, Walter Sickert produced a stinging rebuke of the nude in contemporary academic art. This appeared during the period when, for the first time in his career, the female nude became a central theme in Sickert’s painting. It coincided with his attempts to assert his position at the forefront of modern painting, exhibiting alongside avant-garde artists in Paris and helping to create an avant-garde in London, culminating in the exhibitions of the Camden Town Group in 1911 and 1912. As for many avant-garde artists of the early twentieth century, from Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse to the German expressionists, the nude offered Sickert a potent subject with which to strike at the heart of conventional artistic practice while simultaneously renewing its relevance to modern painting and modern life.2

Sickert’s argument in ‘The naked and the Nude’ was that the nude had become so completely idealised in academic painting and in art school teaching that after decades of artistic inbreeding it had evolved into an ‘obscene monster’.3 He compared it to the ‘living picture’ acts that were a popular music-hall turn of the day (fig.1).4 These consisted of artistes in flesh-coloured body-stockings striking poses that aped highly regarded examples from high art that were familiar to audiences ‘nourished for generations on the Academy and Chantrey bequest nudes’, as Sickert noted.5 For him, these ‘doubly edited and anodyne incitements to the worship of beauty’ were indistinguishable from works by artists who had been taught to turn out versions of, for instance, Frederick Lord Leighton’s The Bath of Psyche, which was first exhibited in 1890 (Tate N01574, fig.2).6 Sickert urged that the nude needed to be brought back into contact with reality so that ‘the student can forget the lifeless formulas of generations of ushers, and see what creative artists have ever seen in the nude’.7

Hana Studios Ltd

Viola Hamilton Posing Naked in a Classical Attitude as Flor c.1900

Photograph

139 x 98 mm

Wellcome Library, London

Photo © Wellcome Library, London

Fig.1

Hana Studios Ltd

Viola Hamilton Posing Naked in a Classical Attitude as Flor c.1900

Wellcome Library, London

Photo © Wellcome Library, London

Frederic, Lord Leighton 1830–1896

The Bath of Psyche exhibited 1890

Oil on canvas

support: 1892 x 622 mm; frame: 2362 x 1187 x 195 mm

Tate N01574

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1890

Fig.2

Frederic, Lord Leighton

The Bath of Psyche exhibited 1890

Tate N01574

Over the previous five years, Sickert had sought to reinvent the nude in his own practice. Although he began this in Neuville and then Venice from around 1902, it was upon his return to London in 1905 that he began to pursue the subject fully. He produced a group of uncompromisingly raw paintings of female models, often posed on iron bedsteads and set in seedy Camden Town lodging rooms which he rented as studios. La Hollandaise c.1906 (Tate T03548, fig.3) epitomises his approach. It is a painting about the stark material realities of flesh and iron. The unflattering fall of Sickert’s light defines the large bulk of the woman’s thigh and her sagging breast at the expense of her face, which is dashed through with the brush and broken up in shadow, the iron bar of the bed appearing to cut her left ear. Sickert assertively strips away conventional idealisations, presenting his model as a naked woman painted with unflinching candour. She is the antithesis of the pre-packaged classical goddesses and nymphs that he so despised in academic painting.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

La Hollandaise c.1906

Oil paint on canvas

support: 511 x 406 mm; frame: 722 x 630 x 104 mm

Tate T03548

Purchased 1983

© Tate

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

La Hollandaise c.1906

Tate T03548

© Tate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Woman Washing her Hair 1906

Oil paint on canvas

support: 457 x 381 mm; frame: 622 x 548 x 75 mm

Tate N05091

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

© Tate

Fig.4

Walter Richard Sickert

Woman Washing her Hair 1906

Tate N05091

© Tate

Citing the example of his friend Edgar Degas, in ‘The naked and the Nude’ Sickert espoused the importance of posing and lighting in unconventional ways and in real surroundings in order to see the model afresh. His group of three paintings produced in Paris of the model Blanche, which includes Woman Washing her Hair 1906 (Tate N05091, fig.4), come closest to Degas’s example of observing the model unawares, as if looking through a keyhole. Yet it was Sickert’s Camden Town nudes that most powerfully achieved ‘a sensation of a page torn from the book of life’, as he put it in another context.8 For many contemporary viewers, Sickert’s naked women sprawled out in murky lodging rooms conveyed strong associations with the dangerous realities of the darker side of modern London life. The French critic Louis Vauxcelles was admiring and unequivocal, describing these figures as ‘whores collapsed on the unmade bed, whores with withered bodies, weary from the harsh work of prostitution’.9 English critics were generally more equivocal. Many could admire Sickert’s technique but struggled to square this with his sordid subject matter: ‘Is Mr Sickert cynical, is he flouting conventional proprieties, or is he really content with these musty, flabby realities?’ asked the Daily Telegraph.10

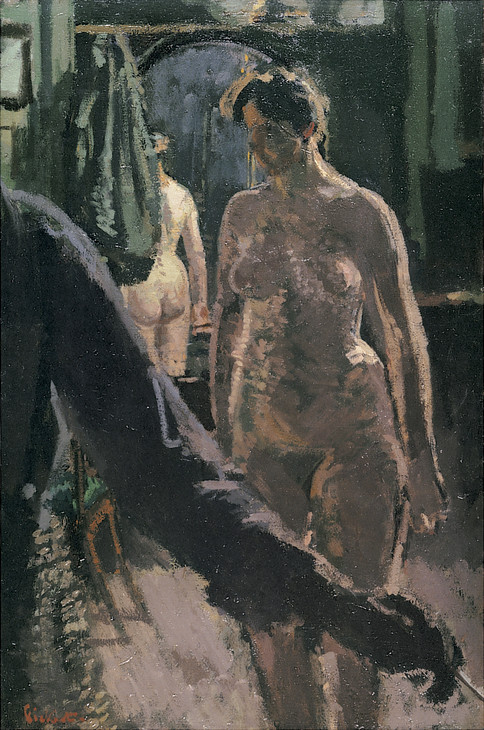

For all their gritty realism, Sickert’s paintings do not simply replace the artifice of the nude with a naked reality drawn from the underside of modern life. If examples such as La Hollandaise undercut moribund conventions then they do so unashamedly and elaborately as contrived studio set-ups in which lighting, props and models are carefully positioned by Sickert’s directorial hand. That hand appears explicitly in The Studio: The Painting of a Nude 1906 (fig.5), which exposes fully what Sickert called the ‘highly artificial game’ of painting.11 This image, composed of multiple reflections within his studio, makes a spectacle out of the artifice of painting itself in which both artist and model are caught in the act. As he makes clear in ‘The naked and the Nude’: ‘There are many artifices that a draughtsman may use to get away from the obsession of the cliché, to keep out of the old ruts of expressions, and find fresh words and living thoughts for truths that are ever young.’12

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Studio: The Painting of a Nude 1906

Oil paint on canvas

750 x 495 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Courtesy of Browse & Darby

Fig.5

Walter Richard Sickert

The Studio: The Painting of a Nude 1906

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Courtesy of Browse & Darby

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

L'Affaire de Camden Town 1909

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 406 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Photographic Survey, Courtauld Institute of Art

Fig.6

Walter Richard Sickert

L'Affaire de Camden Town 1909

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Photographic Survey, Courtauld Institute of Art

The power of these paintings lies in this oscillation between artifice and reality. We see them as studio nudes, set up as artistically challenging subject matter for Sickert’s bravura handling of paint; but this jars with what else we see: naked women in cheap lodging rooms, often fraught with themes of sexual danger. It is with L’Affaire de Camden Town 1909 (fig.6), one of Sickert’s four much-discussed ‘murder’ paintings, that his disruptive approach finds its most complete expression. The inclusion of a clothed male figure in the scene, the naked woman’s explicit pose, and its provocative title (relating to the famous 1907 murder of Emily Dimmock in Camden Town) profoundly unsettle the status of the nude.13

After about 1912 Sickert began to move away from the subject of the nude, perhaps feeling he had exhausted its potential over the previous decade. In stripping away its idealised academic formulae and removing it from a stable context, Sickert had exposed the subject matter’s rebarbative character. Today, these paintings strike us as assertively modern, precisely because they defy categorisation as either ‘the naked’ or ‘the Nude’.

Notes

Walter Sickert, ‘The naked and the Nude’, New Age, 21 July 1910, pp.276–7, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.261. Sickert was careful to distinguish between ‘naked’ (with a lowercase ‘n’) and ‘Nude’ (with an uppercase ‘N’) to underline the elevated status accorded to the academic Nude.

For an extended account of Sickert’s nudes, see Barnaby Wright (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Camden Town Nudes, exhibition catalogue, The Courtauld Gallery, London 2007.

Walter Sickert, ‘The New English and After’, New Age, 2 June 1910, pp.109–10, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.242.

Louis Vauxcelles, ‘La Vie Artistique: Exposition Walter Sickert à Felix Fénéon’, Gil Blas, 12 January 1907; cited and translated in Anna Gruetzner Robins and Robert Thompson (eds.), Degas, Sickert and Toulouse-Lautrec: London and Paris 1870–1910, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2005, p.179.

Walter Sickert, ‘Drawing from the Cast’, New Age, 23 April 1914, pp.781–2, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.357.

For an illuminating account of Sickert’s so-called ‘murder’ paintings, see Lisa Tickner, ‘Walter Sickert: The Camden Town Murder and Tabloid Crime’, Modern Life and Modern Subjects: British Art in the Early Twentieth Century, New Haven and London 2000, pp.11–47. Emily Dimmock’s murder in 1907 and its subsequent trial was front-page news for many months and it quickly became known as ‘The Camden Town Murder’. At a number of exhibitions from 1909 onwards Sickert exhibited four paintings showing a clothed man and a naked woman on a bed with titles which made specific reference to the murder, such as L’Affaire de Camden Town and The Camden Town Murder, despite the fact that none unequivocally depict a murder scene. In some cases he re-titled them for different exhibitions, with names such as Summer Afternoon and What Shall We Do About the Rent?, thus further complicating the extent to which the works can be read as images ‘of’ the murder.

Barnaby Wright is the Daniel Katz Curator of 20th Century Art at the Courtauld Gallery, London.

How to cite

Barnaby Wright, ‘Walter Sickert: ‘The naked and the Nude’’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www