Joseph Mallord William Turner

Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory) - the Morning after the Deluge - Moses Writing the Book of Genesis (exhibited 1843)

Tate

If you put the word 'abstract' into a thesaurus some of the similar words suggested are: theoretical; conceptual; intangible. Among its many antonyms (or words with opposite meanings) is ‘simple’. The word abstract suggests something vague, difficult, not easily grasped. But abstract art doesn't have to be any of those things. On the contrary, an artist working in an abstract way might want to make something striking and beautiful, whisking us away from the humdrum realities of the everyday. In other words, they might be interested in art for art’s sake, pure and simple. A raft of exhibitions show that far from being a hard to describe movement set apart from the mainstream, abstraction in its various forms has produced some of the most memorable, influential and best loved art of any era.

Wassily Kandinsky is often regarded as the pioneer of European abstract art. Kandinsky claimed, wrongly as it turns out, that he produced the first abstract painting in 1911: ‘back then not one single painter was painting in an abstract style’. But we could argue that the roots of this movement are much deeper (and in fact it seems the Neanderthals where ahead of the game in their cutting of abstract lines into stone). If we look at some of the later works of J.M.W. Turner for example, some of his landscapes could be seen as abstract. What might be traditionally recognisable forms in the hands of another painter are transformed by sublime elements, and overwhelming suggestions of light and scale by Turner.

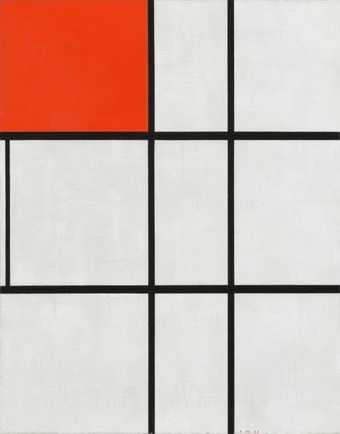

Piet Mondrian

No. VI / Composition No.II (1920)

Tate

Let's come to some of the names more usually associated with abstract art. Piet Mondrian, one of the best known early abstract artists, began in more conventional fashion. He painted recognisable scenes and was commercially successful in his homeland of Holland. But when he encountered avant-garde Paris in 1911, and the cubism of Picasso, his work soon underwent, first an evolution, and eventually a radical transformation. He began to use bold primary colours and squares and rectangles in order to create images that he saw as pure. His angled, gridded work is considered by some to be the logical conclusion of painting, abstract or otherwise. Mondrian called his approach neo-plasticism. With neo-plasticism he aimed to achieve the ‘destruction of natural appearance’, finding instead ‘the plastic expression of true reality’.

Kazimir Malevich

Black Square 1913

© State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Mondrian had neo-plasticism, Russian artist Kazimir Malevich preferred the term suprematism for his abstract artworks. The term referred to ‘the supremacy of pure artistic feeling’ that he wanted to achieve in his work. Although separated geographically, Mondrian and Malevich were startlingly similar. In 1915 Malevich produced his secular Russian icon, Black Quadrilateral 1915 (more commonly known as Black Square). Later, writing in his book The Non-Objective World (published in 1927), Malevich said:

In the year 1913, trying desperately to free art from the dead weight of the real world, I took refuge in the form of the square.

Malevich didn’t paint exclusively in black of course but with Black Quadrilateral, he created one of the most iconic abstract artworks.

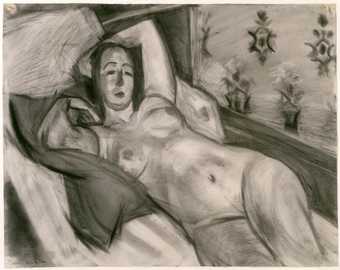

Let's move from Malevich’s daring use of black, to the intoxicating use of colour by Henri Matisse. Matisse's collage The Snail 1953, seems to display the key qualities of abstract art as defined by by Malevich and Mondrian, suggesting that Matisse was a late convert to the movement. We see bold colours, geometric shapes and no obvious reference to the real world. But, as with much of Matisse’s work, The Snail is in fact inspired by nature. The geometric pattern suggests a snail's shell, going against the ideas of strict abstraction set out by Malevich and Mondrian. The Snail may not be radically abstract, but the technique that Matisse used to make this and similar works is groundbreaking. The Snail is one of Matisse's cut outs – made from shapes cut out of painted paper. With this method of ‘carving into colour’, Matisse, in a phase of life when the majority of us would be easing into going with the flow, had invented a new medium.

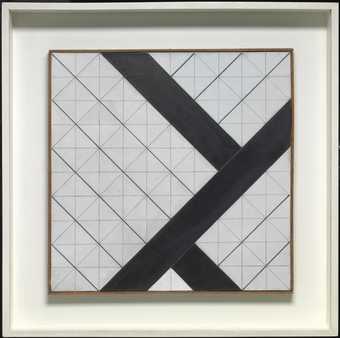

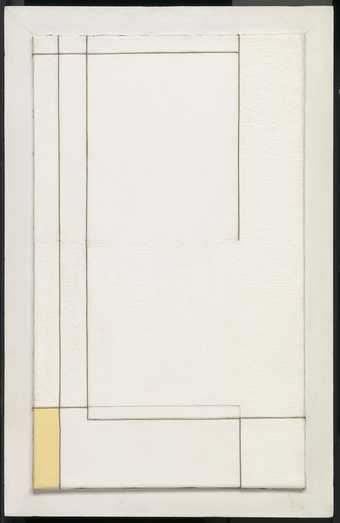

Following the diversion through Matisse, an artist very definitely in tune with abstraction was Marlow Moss. Writing in the Guardian, critic Charles Darwent points out, she was for a time ‘a devoted follower’ of Mondrian’s. Although she is written off by some as an imitator of the father of neo-plasticism, it could be argued that the influence was reciprocal. Her work from the period following her discovery of Mondrian shows his influence, but it was Moss who first introduced twin lines into her gridded compositions in 1931. A year later, Mondrian followed suit, painting Composition with Double Line and Yellow. Largely forgotten in the history of abstract art, Moss’s work, in recent years, is deservedly having something of a renaissance.

Marlow Moss

White and Yellow (1935)

Tate