Carlos Garaicoa

Letter to the Censors (2003)

Tate

Introduction

Letter to the Censors 2003 is an installation by Cuban artist Carlos Garaicoa, acquired by Tate in 2004. Inspired by cinemas, censorship and failed utopias, the piece features an architectural model of a Havana cinema from the 1930s at its centre, with the surrounding walls displaying photographs of old Cuban cinemas in various states of decay.

The model cinema is complete with plush seats, a chandelier and its own very small projector. The projector beams titles of censored films from around the world onto a screen.

The piece has been adapted and exhibited in Rome, Miami, Monaco and Liverpool, and since its acquisition by Tate, has undergone extensive preservation work to ensure its structural stability.

How was it made?

This film file is broken and is being removed. Sorry for any inconvenience this causes.

Garaicoa describes how he investigated censorship in Italy

To make the model, Garaicoa employed a team of highly skilled people including a master model maker and a team of assistants to make different parts. He also employed a sculptor to make the figures and finally, in the weeks before the show opened at Volume! in Rome where the work was first exhibited, he and his wife worked night and day to finish the piece on time.

Censorship is a central theme in the work, and Garaicoa and his studio spent many months researching the issue. He was particularly interested in films that have problems from the outset in the countries where they are produced. Compiling the list of censored films proved to be very difficult, as there is not one source, so instead Garaicoa and members of his studio needed to research film histories in each country.

The Inspiration

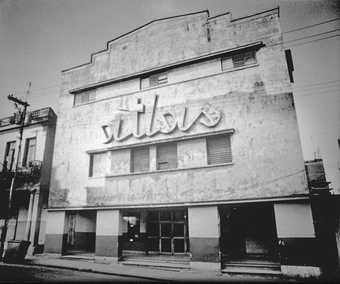

Garaicoa finds inspiration in local situations that he can then relate to more universal themes. For instance, he saw Havana’s crumbling and disused cinemas as symbolic of wider destruction – the destruction of images through censorship. He was also interested in Havana’s architecture as a representation of Cuban identity.

The Cinema in Cuba

As a child, Garaicoa spent much time in the cinema with his brothers when his parents were out. These childhood memories have made cinemas important to him as an artist.

In the early 1990s, cinemas began to close in Cuba because due to a shortage of electricity. Thinking that it would be a temporary situation, people didn’t worry about it at first. However fifteen years later, the cinemas were still closed and many of the buildings were re-purposed or had fallen into disrepair.

“This is a project that is trying to capture the destruction of […] neighbourhood cinemas from the 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s that had been abandoned to ruin and oblivion. The work will consist of several […] photographs of some of these old facades in Havana. These photographs are a documentation of the actual state of these cinemas, as well as of a nostalgic reference to the importance they once had in our daily lives.” Carlos Garaicoa, Press Release, June 2003

Censorship

Censorship is a central theme to the work. Not only are the titles of censored films from around the world projected onto a screen, but there is also a censor’s office. The room is filled with film canisters, unraveled film and a figure of a censor at work cutting films.

The censor's office from outside © Tate Conservation

Inside the censor's office © Tate Conservation

The cinema as metaphor

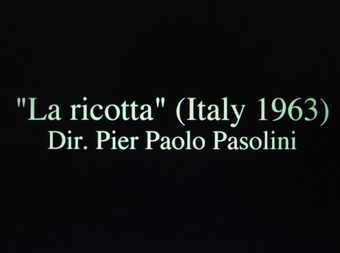

To explore the issue of censorship, Garaicoa uses the cinema as a metaphor for how art is controlled. He initially planned to use the full title sequences of the censored films but ended up rejecting this idea and having the movie without any images. To best echo the theme of image censorship, Garaicoa felt that the titles should be as pared down as possible, so he used simple white text on a black background.

The List of censored films

Garaicoa sees the list of censored films as ‘a work in progress’, which will grow as titles of newly films are added. In the press release for the first presentation of the installation, Garaicoa described his ideas behind the list of censored films, and its impact within the artwork:

“On its [the model cinema’s] screen we will watch a movie without images: a list of censored movies towards the history of cinema. Together with the devastation of the old cinemas, the actual collapse of spaces created for images – a sort of image realm. The image of decay projected by the old buildings only confirms the role of the black screen, the absolute image absence. The perfection of the new cinema model, with all its red velvet chairs, contrasts its inaction. It only conquers us a space, not to watch, only to not forget.”

Censored film title from the video in Carlos Garaicoa’s Letter to the Censors © Tate Conservation

Cities and Utopias

Garaicoa relates the decay of cinemas in Havana to a more universal urban decay and sense of loss and frustration in modern society.

Urban ruins are a large feature of Garaicoa’s work, particularly unfinished or unsuccessful architectural projects that were designed to provide social solutionsl. In works such as Arquitectura ajeba (Somebody’s Architecture) 2002, and Campus o la Babel Conocimento (Campus or the Babel of Knowledge) 2002, he addresses failed utopian schemes.

“Despite its being a work that focuses on a local issue, which is the situation of Cuban architecture in the last 25 years, I think it has a much larger and universal scope: the phenomenon of modernity in its incompleteness and the correlating frustration and decay of 20th century utopias and social dreams” Interview with Holly Bock, Bomb 82, Winter 2003

About the Artist

Photograph of Garaicoa at work © Carlos Garaicoa, Volume! and Rodolfo Fiorenza

Carlos Garaicoa was born in Havana, Cuba in 1967. During his time in mandatory military service, he worked as a draughtsman and produced maps and technical drawings by hand. This was the first time he came across draughtsman’s tools and where he learnt the skills he would use later as an artist.

At twenty-two he enrolled at the Havana Instituto Supierior de Arte where he studied from 1989 to 1994. It was while at art school that he became interested in the language of architecture.

Garaicoa first discovered the language of model making in a piece he made for Documenta 11 in 2002. Rather than creating dry architectural models, he has explored ways of making this language warmer – more human and more sculptural.

Although based in Havana in Cuba, Carlos Garaicoa has exhibited extensively around the world. His works have been included in major international exhibitions such as the Kwanju Biennale, Korea (1997); the Biennale of Sao Paolo; and DocumentaXI (2002). The scale of the projects he is involved with has required a collaborative approach to working, often involving a large studio of assistants, architects, model makers, sculptors and designers in the production of his artworks.

Where has Letter to Censors been Exhibited?

Letter to the Censors was first commissioned in 2003 for the art space Volume! in Rome. Since then it has been displayed at Art Basel Miami (an art fair where it was acquired by Tate); in Monaco and at Tate Liverpool. As it was designed for a specific gallery space, its appearance is adapted for every subsequent installation.

Miami Art Basel

Carlos Garaicao, Letters to the Censors (Carta a los censores) 2003

View inside the model, Miami Art Basel © Carlos Garaicoa. Photo: Tanya Barson

In December 2003, Letter to the Censors was presented by commercial gallery Lombard-Freid Fine Arts at the art fair Miami Art Basel. Under stricter controls by the Bush administration, Garaicoa was unable to attend in person since his visa request had not been processed. Instead he relied on assistants and staff from his gallery to install the work. ‘My friends kept calling me and e-mailing about the work and to find out when I would arrive. It was so sad’, the artist told Marc Spiegler in an interview for Artnews, in March 2005.

In the display in Miami, the model was placed on a red carpet in the centre of a room surrounded by the light boxes which were hung on the walls. Spotlights were fixed to the bottom of the walls pointing downwards. It was at this art fair that the work was acquired by Tate.

Monaco

Venue: Salle d’Exposition du Quai Antoine © Photo: Tate Conservation

In 2005 Carlos Garaicoa was awarded the prize of laureate for Fine Arts, and Letter to the Censors was requested for loan for an exhibition in recognition of this award, which was to take place in Monaco - the XXXIXe Prix International d’Art Contemporain de la Fondation Prince Pierre de Monaco.

Garaicoa often looks to work and exhibit outside of formal spaces such as galleries or museums, so he originally considered using an old cinema for this display, Théâtre Princesse-Grace / Centre de Rencontres Internationales. However due to the piece requiring a climate-controlled environment, he agreed to show the work in the exhibition space Salle d’Exposition du Quai Antoine at the other side of the harbour.

The Installation

In Monaco, the core elements of the installation became more formalised. The model was placed diagonally in the exhibition space, the lighting was dimmed and red carpet was laid on the floor. The cinema-type lighting was placed around the bottom of the walls and the model was carefully lit with eight spot lights arranged in an oval on the ceiling, and the ten light boxes were shown on the walls surrounding the model.

Whilst only being open for six weeks, the show provided a useful opportunity to clarify some of the display issues associated with the work, such as lighting and fragility. The lighting for the piece had to be bright enough to show the artwork but dim enough that it wouldn’t wash out the projector’s beam inside the model. As a solution, fairy lights were positioned within the cavity walls and the opening was covered with a red plastic lighting gel. Another issue that arose during this display was the risk that people posed to the model by too close to it in order to read the film titles inside the cinema’s auditorium. In response, he also presented the titles of the censored films in an adjoining space on white vinyl wallpaper that covered the entire walls.

Tate Liverpool

Carlos Garaicao, Letter to the Censors (Carta a los censores), 2003

Display view, Liverpool 2005 © Carlos Garaicoa. Photo: Tate Conservation

In October 2005, the work went on show in a display organised by Tate Liverpool called Inverting the Map: Latin American Art from the Tate Collection. The work was displayed in an almost square space (8 metres x 9 metres) which could be entered from two sides of the gallery. The lighting, carpet and diagonal position of the model followed the design developed in Monaco and Miami. Cavity walls were built lengthwise to the model to facilitate the floor lights and the mains adaptors for the light boxes. Five of the light boxes were hung on each wall with floor lights placed in between. In this display the film titles were shown on a 20.1” LCD monitor mounted on the wall next to the entrance.

Looking After the Installation

Carlos Garaicao Letter to the Censors (Carta a los censores) 2003,Dismantling the model © Carlos Garaicoa. Photo: Tate Conservation

When Letter to the Censors was acquired for Tate’s collection in 2004 at Miami Art Basel, the first task for conservationists was to examine its physical structure and see whether it needed to be fixed or stabilised. This is so that it could be re-installed when required without the continued work of the artist.

Once the work was unpacked, several of the small elements were found to have been lost or broken in transit. Whilst it was unclear at what stage they’d been damaged, it was obvious that the work was highly vulnerable. The electrics also needed to be upgraded to satisfy British safety standards and to prevent the build up of heat in the model. In addion to these missing and misfunctioning elements, it was quickly recognised that the work would be vulnerable whilst on display, since visitors would inevitably want to get close enough to see inside the model.

The Model

The model is made up of many different and intricate sculptural elements that have each required expert fixing and preserving.

The Chandelier

Chandelier with twinkling lights © Carlos Garaicoa, Photo: Tate Conservation

The chandelier is made of clear plastic with separate beads and swags. Originally the chandelier was lit with a single small bulb but there were concerns about how this could be accessed to be changed. The artist was consulted and it was decided that the lighting should be ‘twinkly’. After some experimentation, thirty-two fibre optic strands were used as a substitute for the original bulb. Each fibre can be clipped at any point, revealing a light beam of the same diameter as the fibre. These fibre optic strands were threaded through and around the perimeter of the chandelier. Where necessary, the fibres were tied to the chandelier with nylon thread, with the intention to position the ends of the fibres to imitate a three-tier chandelier when lit.

The brass wire, which holds the chandelier in position, is pushed through the hole in the ceiling together with the fibres and is tied around a screw next to the hole. The fibres were then connected to its light source, which is placed in the projection space allowing for easy access should the lamp fail and need to be replaced.

The chandelier was repaired using Balsa cement, a cellulose nitrate adhesive, chosen because it enabled the conservator to reattach the broken parts without applying weight. This was essential due to the chandelier’s fragility.

Brackets and Lanterns

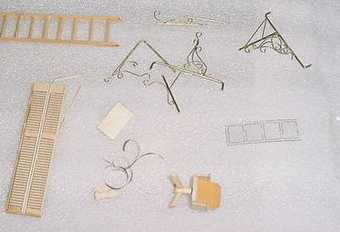

Brackets and other sculptural elements which had broken off the model during transit © Carlos Garaicoa, Photo: Tate Conservation

There are twenty-nine miniature lanterns made from very thin balsa wood which hang on brass wire brackets attached to the outside of the model. Several of the brackets had become loose during transit or were lost and needed to be re-adhered or remade. Of the twenty-nine lanterns, half had been broken or had missing elements. All the loose pieces were re-fixed and missing elements were replaced using thin balsa wood which was stained with water colours to match the originals.

Balustrade, finials, columns, pilasters and scaffolding

Broken elements along the balustrade © Carlos Garaicoa, Photo: Tate Conservation

There were numerous areas of loss and damage to the architectural details of the model. In some cases repairs could be made, whereas other elements had to be re-carved. These were carefully documented in the conservation report so it would be clear in the future which elements were original and which had been remade.

The Readagraph

Readagraph above the main entrance of the model: the announcement is in Italian as the work was first shown in Italy

© Carlos Garaicoa, Photo: Tate Conservation

The readagraph, which displays the title of the work, the ‘director’ and the cinema’s opening hours at the front entrance of the model, was repaired as some of the letters and the wires which are used to attach it to the façade had become loose.

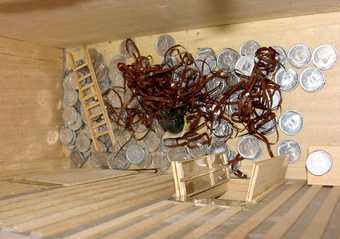

Censor’s Office

Condition of the censor’s office post transit © Carlos Garaicoa, Photo: Tate Conservation

Elements within the censor’s office had become loose. The silver coins, which represent reels of film, had spilled from the shelf onto the floor. The old adhesive was removed and the ‘cans’ were arranged back onto the shelves, loosely following a pattern recorded in a photograph supplied by the artist. The adhesive used was Paraloid B72 an ethyl methacrylate copolymer.

© Tate Conservation

The Figures

The figures are hand-modeled and finely detailed, each one displaying individual character. The conservation team were concerned about them as they were known to be made from an unstable material that remains slightly soft, leaving them vulnerable to damage from handling and encouraging the build up of dust.

To find out what exactly they were made out of, the figures were analysed by Conservation Science at Tate using FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy). It was discovered that the material used is a mixture of beeswax and chalk with a dark green pigment added for colour, then coated with varnish. This modelling material, similar to Plasticine, deteriorates with age as the beeswax becomes brittle and shrinks with oxidation.

During transport eight figures suffered broken limbs and/or heads. Although all of the broken pieces were reattached with a specialist glue (a cynoacrylate adhesive), the risk of loss or future damage to such a key part of the work, was significant.

Preserving the figures

The conservation team and curator felt that the best way to ensure the figures are preserved would be to make replicas for display enabling Tate to preserve the original figures in a controlled environment for future reference.

In collaboration with the artist, Tate Conservation explored different options for the preservation of the original figures. Three possible options were identified: producing replicas by casting the figures, remodeling the figures by hand out of a more stable material or remodelign the figures using 3-dimensional scanning and rapid prototyping.

The idea of producing cast replicas was dismissed as impractical given the fragility of the original figures.

Initial tests were carried out to re-model the figures by hand using Milliput superfine white – a two part epoxy putty which is commonly used by plumbers – but It quickly became clear that it was going to be both difficult and time-consuming to replicate the individual gestures of the figures using Milliput.

The third option explored was 3-dimensional laser scanning and rapid prototype modelling, a technique that enables exact replicas to be made, and this proved the most successful.

How does T3D-Scanning work?

This film file is broken and is being removed. Sorry for any inconvenience this causes.

Conservator Neil Wressell explains the 3-D scanning process

This method of scanning makes the production of an accurate 3-D computer model of the original object possible without the need to make contact with the object’s surface.

Sound and Video

To allow for updated technologies and also to compensate for the potential degrading of video and audio, it’s Tate’s standard practice when conserving video to hold a preservation master in an uncompressed format. This can then be migrated every five-six years onto new stock and if necessary, new formats. In order to create this preservation master for Letter to the Censors, Tate borrowed material from the artist.

The format of the audio and video files for the exhibition is called MPEG-2, and are played back using a small computer-based MPEG-2 player. The projector used is a DLP (digital light processing) projector made by DreamVision. These devices were chosen because they are small and reliable and fit in the small space above the foyer in the cinema model.

As the projector is used, it creates heat and raises the temperature inside the foye, causing the space above the foyer to hear up.The increased temperature then caused the roof to warp and the joints of the construction to open. Temperatures above 40°C also affected the electronic equipment causing it to overheat.

In this video, conservator Tina Wiedner describes how the solution to this problem of overheating was found and tested:

This film file is broken and is being removed. Sorry for any inconvenience this causes.

Tina Weidner on the cooling system for video and sound

Lightboxes

The light boxes that are used to display photographs of crumbling cinemas were made so that the fluorescent tubes inside them could not be changed when they failed. Metal clips in the boxes hold the fluorescent tubes, and these were bent and had been soldered to the pins at both ends of the tubes.

Preparing for Transit

Tate designed two new packing cases to store this fragile work safely and minimise the risk of damage occurring in transit. The model is packed on its own in one crate, with the electronic equipment and metal frame in the second crate. After much discussion, it was decided that model should not be wrapped in tissue because the risk of it catching and breaking the fragile details was greater than the protection offered. Instead, the model rests on foam blocks made from a stable closed-cell polyethylene designed to absorb vibration and shocks. The small elements such as the figures and lanterns are kept in plastic boxes which are packed in a storage bin. Even with these new cases, it’s unlikely that the work can be moved without minor damages occurring.