John Constable, David Lucas

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows (published 1855)

Tate

David Lucas and the mezzotints

We often first know about important artworks from photographs, rather than seeing them in real life. But before the invention of photography, artists employed print-makers to make copies of their works. These prints were widely circulated, ensuring that the art – and the artist – became well-known.

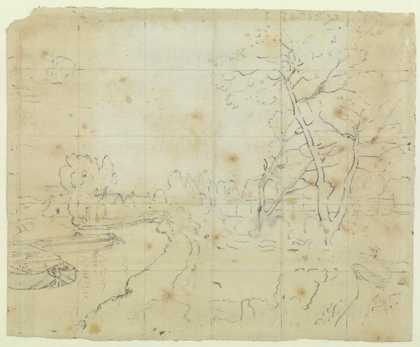

John Constable commissioned the talented engraver, David Lucas, to make prints of Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows 1831. Lucas had worked with Constable for a few years already on English Landscape Scenery, a portfolio of prints after Constable’s paintings. Lucas worked in mezzotint, a printmaking technique that came closer than linear engraving to the texture and finely gradated tonality of painted brushstrokes. The lighter areas in the print are the result of scraping and burnishing away at a pre-inked metal plate – the more scraping and burnishing, the lighter the area.

Lucas’s print of Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows’s was the largest of the prints he made after Constable’s paintings. He worked on it painstakingly and it took him six months to create the initial proof. But Constable continually worried about the result, wanting it to be perfect so that it did justice to his masterpiece. In a letter to Lucas he refers to ‘our rainbow’, saying that ‘if it is not tender – and elegant – evanescent and lovely – in the highest degree – we are both ruined’.

Constable continued to instruct Lucas to tweak and perfect the print over the following two years right up until his death in 1837. On 29 March 1837 Lucas was told to ‘Go on as you think proper’. Constable died two days later.

Delacroix, The Barbizon School and impressionism

John Constable

The Hay Wain 1821

Oil on canvas

Courtesy The National Gallery, London

In Britain, Constable’s popularity slumped away towards the middle of the nineteenth century. The Pre-Raphaelites, who took a very different approach to nature, were the next big thing; and John Ruskin, one of the most influential art critics of the Victorian era, was a harsh critic of Constable’s work.

But if Constable’s art was not greatly appreciated in Britain, things were very different in France. In 1824 Constable exhibited some paintings, including Hay Wain 1821, at the Paris Salon. The paintings caused a sensation.

Artist Eugène Delacroix was apparently so struck by Constable’s use of broken colour and flickering light that he repainted the background of his dramatic masterpiece Scenes from the Massacres of Chios 1824. When Delacroix visited London in 1825 it is probable that he paid a visit to Constable’s studio, as his journal includes an accurate account of Constable’s technqiue.

Constable’s approach also inspired artists to work directly from everyday life and use nature as the main subject of their painting – rather than simply as a backdrop for dramatic classical or historic scenes. They began to venture out of Paris and into the countryside to work directly from the landscape. A main destination was the Forest of Fontainbleu, an easy train-ride from Paris. One of the villages on the edge of the forest, Barbizon, became a popular place for artists to stay during their sketching trips. These artists, including Theodore Rousseau and Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, later became known as the Barbizon School.

The Barbizon painters also responded to Constable’s handling of paint. The broad strokes and loose marks in Constable’s paintings seemed to record the vigorous movements of the artist’s hand, unlike academic conventions which tended to suppress those kinds of traces. Another artist associated with the School, Jean-Francois Millet, added a human dimension to this new approach to landscape painting. In paintings such as The Gleaners 1857, farm workers are shown harvesting or labouring within the landscape. There is no drama or narrative, simply the documenting of everyday life.

Parallels between Constable’s rapid and spontaneous handling of paint, open-air naturalism, and direct response to the immediate environment can also be drawn with the French impressionists. However, although impressionists such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro were aware that their work was discussed in relation to the influence of Constable (and fellow British landscape painter J.M.W. Turner); they in fact rejected this suggestion. Constable’s influence is more directly apparent on British impressionism. Philip Wilson Steer’s scenes of the English landscape and everyday life, captured with loose, light dabs and smears of paint, clearly acknowledge the legacy of Constable.

Freud and Constable

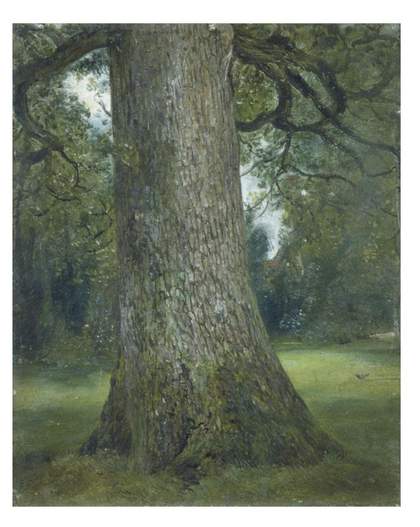

John Constable RA

Study of the Trunk of an Elm Tree ca. 1821

Oil on paper

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Although best known for his powerful portraits, the British painter Lucian Freud, was a huge fan of Constable’s work.

At the age of seventeen Freud went to study at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing in the heart of ‘Constable country’. He at first thought that Constable’s work was both ‘ridiculous’ and ‘soppy’. But he saw and liked Constable’s Study for the Trunk of an Elm Tree c.1821 and tried to paint a copy of the work – though gave up because it was too difficult. (Years later he produced the etching Elm Tree after Constable in 2003).

Freud’s appreciation of Constable’s painting and the feeling behind it deepened as his own work developed. Although initially drawn to Constable’s land-focused oil sketches, which he described as ‘completely fresh, really passionate pictures’, he then realised ‘how marvellous the portraits were’. He said: ‘I’ve always thought it completely loopy for people to go on about portrait painters, English portrait painters, and not to have Constable among them.’

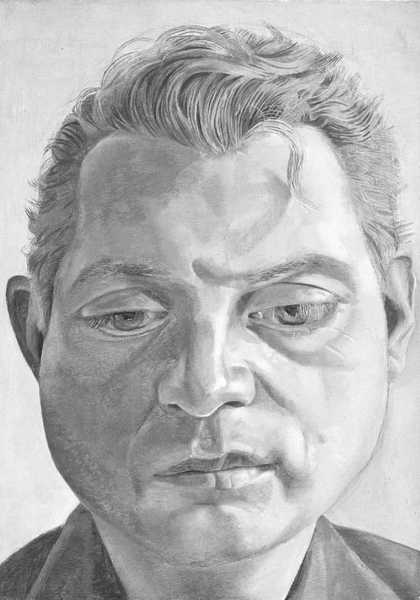

And this is perhaps where the similarities between Constable and Freud are most clearly seen, in the relationship between artist and subject. Just as Constable’s landscape paintings demonstrate a close focus on place and the changing face of nature, his studies of people encourage an intimate view of an individual and reveal something of their relationship with the artist. Similarly Freud’s portraiture depicts the intimate relationship that he shared with his sitters. Martin Gayford, who sat for Freud towards the end of his life, suggested that Freud sought to capture his model’s individuality, and felt that his portrait seemed to ‘reveal secrets – ageing, ugliness, faults – that I imagine … I am hiding from the world.’

John Constable

Golding Constable (1815)

Tate

Lucian Freud

Francis Bacon (1952)

Tate

Kossoff and Constable

Artist Leon Kossoff created a series of prints in response to Old Master paintings. For Kossoff, printmaking is another form of drawing. By studying images by older artists and interpreting them in new ways he feels close to them and gains a deeper insight into their work. He has commented:

[My] attitude to these works has always been to teach myself to draw from them, and, by repeated visits, to try to understand why certain pictures have a transforming effect on my mind.

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows 1831 was one of the works that inspired him, and he made a number of prints in response to the painting.

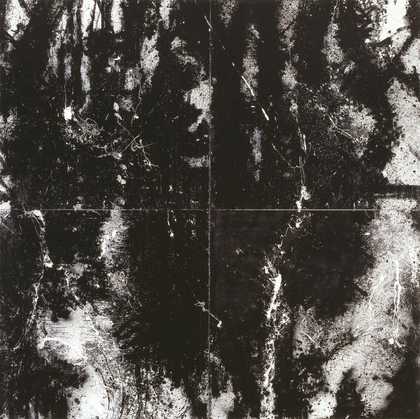

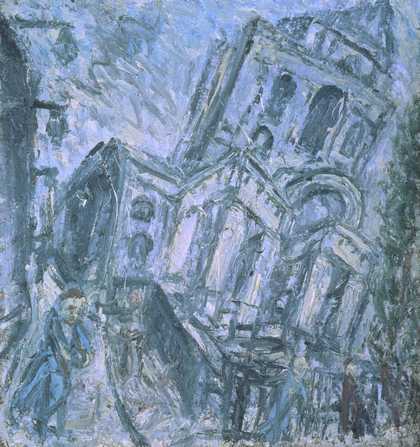

Leon Kossoff

From Constable: Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows (plate 1) (1996–7)

Tate

Leon Kossoff

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows (1) (1998)

Tate

But as well as directly responding to Constable’s work in his prints, a similarity can be seen in the way Kossoff uses paint. Both artists use thickly-laid paint – a technique called impasto. It gives an almost sculptural quality to the works.

Tate Curator Amy Concannon has commented on other similarities between Constable and Kossoff’s approach:

There’s a work by Kossoff in Tate’s collection featuring Spitalfields church, which is painted in a cool colouring and bends so as to be seen within the square canvas but still towers above the street, reminding me of Salisbury Cathedral’s towering spire and the cool atmosphere of Constable’s painting. In others like Willesden Junction, Morning in October 1971, Kossoff presents an expanded perspective – a panoramic view – which takes in lots of elements. Constable was also aiming for this expanded view in Salisbury (you can’t really see everything you can see in the painting from his supposed vantage point). Another point of common interest between the two is atmospheric effect. Both these works by Kossoff contain reference to the time of day they depict, something Constable often did, too.

Leon Kossoff

Christ Church, Spitalfields, Morning (1990)

Tate

Contemporary responses to Constable

Use this slideshow to explore the work of other artists who have been directly influenced and inspired by Constable: