Time is the best friend for an artist. Just be in your studio and think, that’s what artists have to do and the depth and the strength is coming by itself by just, you know giving it the space also to grow around you.

I was born at the countryside where my grandparents had a farm. I was actually just inhaling nature and growing up in a garden. Like my earliest memories of the garden were like picking tomatoes from the bush and just you know, eating it and climbing on the tree eating apples, cherries, everything. It was really like an outstanding childhood I would say.

I was quite connected to myself, because my mum gave me really a sense of expressing my ideas, expressing my inner drive and I think later that also helped me to kind of compensate a lot of emotions I had by you know racist encounters and feeling you know a little bit like as an outsider sometimes. My father was an Ewe-Ashanti based in Upper Volta region and he was a traditional leader and coming to visit him the first time in 2003 I realised that I'm actually under a cultural shock. Seeing him as a chief, with all the Ashanti culture around I have not really experienced anything like that.

I believe that your soul or your spirit speaks with you and tells you what you want. If you're really able to listen, if you can calm yourself and be really aware then you actually know where you want to be.

I had actually a workshop announced here in Ghana, I decided I will not buy a flight ticket back I will just stay. I was very excited and inspired by what happens here around me, especially the artistic minds I encountered. I realised that I can learn a lot here and can bring my background and experience into a new kind of imagery.

Sometimes when I see my assistants stitching, by hand you know, like doing this kind of really meditative kind of movement, you know all day I really see my grandma and my mom

sitting knitting or doing embroidery together at home and that really stuck with me. This kind of communal sewing and taking the time to create something out of nothing. When you stand in front of the work you can really see that there is like this long process of labour, but with love and care.

When I came the first time to Ghana it was like this kind of key moment seeing a little boy wearing a soccer club T-shirt in Upper Volta region, I’m like, how did that T-shirt come here? And also because it was not really a soccer club I would support because they were quite right-wing. So I started researching on it and found out how the entire industry in Europe were collecting all these unwanted goods and started shipping them since the seventies.

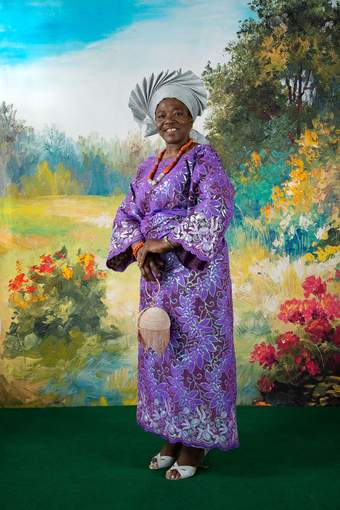

Queens and Kings I wanted to show a very traditional set-up of the king, the queen mother, the family around plus the medicine men and the guards and then bringing in the opposite like something what is old and unwanted coming from the West, dumped here and then put back on the people. If you would take also the sector out now from the market, then a lot of people would lose their jobs. They identify themselves with their jobs and what they have and what they are selling. It brings them further away from for instance, the Ashanti culture like just an expression of both sides we are dealing with. I believe, for an artist it’s very important to have this critical perspective. I wouldn't call myself an artist if I just create something beautiful, it's more in the process of reflecting and what is happening here around me I can't ignore. I am political with my work because I also want to express my thought process. I wouldn't become a politician, but I definitely would love to be the whisperer to one.

I'm quite an analogue girl. I'm an analogue girl in a digital world. So I was really happy when I got introduced to screen printing. Realising how I'm able to influence the process by how I create the bitmap, how I choose the colour, how I choose the pressure of the print, how the material is actually having a conversation with the textile. Because it always depends what texture it has If it is roughly or like fine weave.

A photograph doesn't do justice to the actual work and I believe it's like this with most artworks. We need to actually almost dive into it and I think that's also what I want to achieve. I create a scale which makes me wanting to actually step almost into it, like opening a door and you know, being with the artwork.

Outside of being an artist there's nothing, I mean, you don't stop, right? But I learned to divide my private life, because since I have my adopted son with me I also realised how important it is for him, not to have art around all the time. Even though I almost believe he is becoming an artist himself. I think motherhood also changed a little bit my routines and now it's more like. Oh, I should come home to have dinner with Junior. It's also important to just close the chapter of studio work and now I'm you know, just Zohra and can also relax my mind. But it took me many years to actually come to this conclusion, I should also have more time.

Artist Zohra Opoku trained as a fashion and textiles designer, and her works combine fabric with photography to interrogate identity. In pieces like Queens and Kings (2017), she explores the ways that tradition and globalisation intersect in modern day Ghana.

In this short film, Opoku invites us into her studio in Accra, Ghana, to witness her collaborative approach to art-making.

Zohra Opoku

Queens and Kings (2017)

Tate