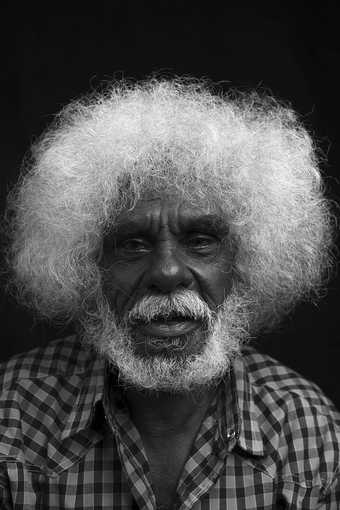

Yhonnie Scarce. Photograph by Janelle Low

Please note, this article contains names and images of deceased Aboriginal peoples. The words Aboriginal, Indigenous and First Nations are used interchangeably throughout the text.

Glass sits at the centre of Yhonnie Scarce's artistic practice. Through a wide range of installations that draw on sculpture, architecture, photography and textiles, Scarce uses this material to challenge official narratives about the treatment of Indigenous peoples in Australia and to restore dignity and respect to her family.

Clothilde Bullen, Head of Indigenous Programs at the Art Gallery of Western Australia, speaks to Scarce about their practice, the appeal of glassblowing and the importance of honouring her ancestors through her art.

Clothilde Bullen: It's difficult to know where to locate the beginning of this conversation because often we as First Nations people locate ourselves in Country* and also through our ancestors, a timeline that stretches back through millennia - rather than what we do.

Let's start with you in the context of the places you and your ancestors are from. About the places and locations that your elders have custodianship of, and the importance of those locations that's revealed in your work.

Yhonnie Scarce: My Country is Kokatha and Nukunu in South Australia. I do have ancestral ties to Mirning people, which is a part of the Great Australian Bight. Kokatha is the largest language group in South Australia.

Nukunu is the southern part of the Flinders Ranges in South Australia, so that's my grandmother's Country, and Kokatha Country is my grandfather's homeland. Interestingly enough I was born on Country at Woomera which was once a rocket range. It's still quite active as a military base even though it doesn't look like much these days.

Bullen: The places that we come from, I think for any artist or any creative has an impact on identity and on what you make. Particularly in your circumstance as an artist, you draw upon those locations very specifically in your work. It's probably good to mention the location of Woomera and Maralinga – a specific site where nuclear testing took place. I think it's really important to mention that because unless you are from Australia you might not understand the vast distances of the places that you are from. The distances between stop-offs, the vast tracts of land that are in those spaces. That too has had an impact on your work.

Scarce: Woomera is five hours north of Adelaide by car, and then it's I think around six or seven hours between Woomera and Maralinga. If you were to drive from Port Augusta in South Australia through to Ceduna that's six hours. Maralinga is another three on top of that.

Bullen: You are singular in the ecosystem of First Nations artists and art. You work in photography as well, but you work in glass in a way that no other Aboriginal artist does, in the sense that you create these huge sculptural installations.

You also chose to learn the technique of glassblowing yourself. How did you begin and what was it about working in glass that attracted you?

Scarce: I remember first getting the internet, and looking at videos of glass blowing. I used to find paperweights and was fascinated about how the bubbles got inside them. I started searching for information... it's a form of glass blowing, but we call it ‘hot forming’. You still put air in it but you don't necessarily see too many bubbles. It was something I hadn't seen before.

I liked art in high school, but we were told that visual art wasn't a decent job. I didn't pursue it until I started finding these glass pieces in charity shops. I discovered that the University of South Australia offered glass-blowing as a subject and as a specialisation in their fine arts degree. I decided to leave my job and go to art school.

Bullen: That's a gutsy move.

Scarce: Yes, I think at that time I'd had enough of my job. I just made a decision over a weekend that I either stay in this job for another three years or I leave it and go to university. I was a mature age student then. It was a big deal to leave full-time work. It was the best thing I ever did.

Thinking back I often wonder whether glass chose me instead. At the time I wasn't looking for it. It was presenting itself.

Bullen: That's what they say about great loves in our lives - that when we're not looking for it, it chooses us.

Scarce: I miss glassblowing when I'm not doing it. I say it is very much a love affair with this medium because it's very seductive and very, very harsh. It does make you work for it. There are moments of temperamental behaviour and things like that.

Bullen: Direct tragedy as well, I would imagine.

Scarce: Yes, yes, you have a few losses. I don't worry about it too much anymore. I think [those pieces] weren't meant to exist. Those pieces for whatever reason didn't make it. Hetti Perkins [curator and writer] said once that I come from desert and desert-like sand that meets lightning or any extreme heat turns to glass. I think it's very much a part of myself. I often say that all those glass pieces I create are an extension of myself.

Yhonnie Scarce, Fallout Babies 2016. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Yhonnie Scarce, Fallout Babies 2016. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Bullen: You talked about glass being a love affair, but what did it feel like when you completed your first work in glass? Do you remember what it was?

Scarce: Yes. I made a puffer fish at art school. [laughter] It was quite big and I was so proud of myself because you have to be physically strong to be a glassblower. I was like, wow, this is the biggest piece I've ever made, and that's when I first started integrating other materials too.

Bullen: Do you still have that puffer fish?

Scarce: My sister has it, I think. That was the only big piece I made really, and then I went back to making smaller work.

Bullen: Because particularly your large-scale installations some of them are small but there's a multitude of them.

There are many threads and points of concern and interests that you tackle in your practice. I'd like to focus on the entwinement of religion as a tool of colonisation, and the ways in which you speak to this in your practice.

What They Wanted (2007) is very clear in its intent and purpose in that it speaks to this entwinement. It's composed of glass figurines arranged in the shape of a crucifix, and each figurine has rope around their neck.

Yhonnie Scarce, What They Wanted 2007. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Yhonnie Scarce, What They Wanted 2007. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Scarce: I produced What They Wanted two years out of art school, I think. That's the only work that doesn't feature the bush food, but the bodies themselves still have that shadow effect of a deceased bird, or an animal. I think at that time I was really thinking about the Christian missions particularly in South Australia, obviously because that's where I come from. The stories around those missions being very prison-like. I call them concentration camps because the whole purpose of those missions was to kill off our culture and kill off our language, and take the children away and keep families separated. The Lutheran mission that my grandfather was born in, I remember growing up and mum saying that he couldn't wait to get out of there, but then sadly he was returned to be buried there when he passed away.

It's very much a part of who I am. I return to that place every time I'm in Ceduna in South Australia when I'm visiting my extended family. I always return there because my grandfather is buried there and so is my uncle and other family members. It's still for me an oppressive place, even though they have reclaimed it as a community. To me it's still a mission and the church is still very present and prominent. I was talking to someone about that church recently. It didn't really occur to me how obsessed I am with it because I've got hundreds of photos of it. Every time I go to Koonibba Mission, I always take photos of it and its different angles.

Bullen: That feels very much like a ritual. You use photography in your work a lot more, recently. Taking and retaking an image of somewhere that has had such a tie directly to your immediate family, it's almost like enacting a ceremonial ritual to keep them safe.

Scarce: Yes. I always stop in front of it before I leave, and that's when I take the photos.

Bullen: Maybe that's what we have to do now when we can't enact our own ceremonies and rituals in those places because they were stripped out from those places. The missions did not allow that. Religion took over that. Maybe that's our way of reclaiming that by enacting new ceremonies and new rituals.

Scarce: [They wanted] to assimilate us into white Australia and then for me to return as a descendant, the granddaughter of one of the men who was born there, and I'm returning and I'm exactly not what they wanted. I'm exactly the opposite. It's pushing back on that and actually throwing it back in their face.

Bullen: It's an active process.

Scarce: Yes, because when those missions were created we were considered savages as Aboriginal people. We weren't considered highly intelligent people. That work itself was about all those people that died on the missions. Some people talk about Black deaths in custody relating to that work. I can see that too.

Bullen: Whilst that work is about a specific place, it feels like something that we all understand if you're a First Nations person, and not just in Australia because in other colonised countries there was missions, there is still police brutality which happens to Aboriginal people, targeted harassment and other things. I think First Nations people globally have had similar experiences with religion, with the police, and other powers that be. I think for me that work really cuts through what it is to be a First Nations person essentially subjected to particular structural intervention. Whether that's via God, or whether that's via incarceration, or whatever it might be.

I'd like to talk about Missile Park (2021) because it's intimately connected by its location to the Lutheran Mission at Koonibba on the lands of six different custodial groups. That's a huge area.

Scarce: The Woomera prohibited area, yes. It's the same size as the United Kingdom. That's how big it is.

Yhonnie Scarce, Missile Park (2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Bullen: Missile Park itself refers to the public plaza situated at the front of the now-closed Woomera History Museum. The museum collected objects from the Woomera exclusion zone, which is 127,000 kilometres of land.

Can you tell me a bit about that work and how that all came about and what you wanted to say?

Scarce: The work Missile Park was commissioned by the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art. It was commissioned for an exhibition in 2021. I was thinking a lot about my birthplace and I guess if I was to create a new work it would be quite large scale, and it's the largest artwork to date really besides my public artwork. I wanted to create something that gave people the idea or the sense of what buildings were out in the Woomera prohibited area. Also that military occupation in South Australia during the nuclear tests by the British and Australian governments.

I thought it had to be about where I came from, and my interest in architecture, my interest in the militarisation of my Country; the detrimental effect of the nuclear tests, not just on my Country, but the Country of others in South Australia, and how it affected all Aboriginal people and non-Aboriginal people. Also, how it was covered up for so long by both governments. The sheds themselves, they're not just tombs, they're keepers of secrecy. Those large bush plums that you find inside the sheds are time bombs waiting to go off.

Yhonnie Scarce, Missile Park (2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Yhonnie Scarce, Missile Park (2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Bullen: For those who haven't heard of bush plums before, can you explain what they are?

Scarce: You find them along the coast of South Australia, they're actually quite small. They're like salty watery plants. They're probably only five centimetres in length, they're round. They're a tiny little fruit, not so sweet. We still have them as our food. I would eat them when hanging around that way, and if they're not yet dried up by the sun.

Bullen: That testing took place, I think, between 1956 and 1963, which is an extensive amount of time. As you said, both governments were complicit in that testing because there was the attitude that there was no one out there that mattered.

Scarce: I think a lot of people don't know or are not aware that during the time of those nuclear tests, Aboriginal people were not considered citizens of Australia. We came under the Flora and Fauna Act.

Bullen: They weren't counted in the census either, so technically, it wasn't murder if those people didn't exist.

Scarce: Yes. I think that's how they got away with a lot of that. Who knows how many Aboriginal people died out there during those tests? Sadly, we may never know because we were not considered worthy enough to be saved. It's disgusting behaviour. It's something that will stay with me forever.

Bullen: You've traveled extensively. You traveled to Japan, Ukraine, Germany, the US. You have been to some significant sites which have a history of harm due to war, military intervention, nuclear disaster, particularly in the US that was a site of frontier conflict as well. The reason for that, I think, was to seek connections between those places and what's occurred in places like Woomera and Maralinga. Can we talk a little bit about how those journeys have contributed to your practice?

Scarce: Yes. For me, fieldwork is really important. I have been traveling quite a lot for 15 years, and first started researching genocide internationally in 2008.

It's been a large part of who I am as an artist. For me, it's important about being on site, and getting a sense of what their Country is like. I think as Aboriginal people we talk about Country having memory and memory of trauma, and it stays in that area until it's healed properly.

It's very similar overseas. I visited concentration camps... Auschwitz and Birkenau. [I went to] Wounded Knee at Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, then Chernobyl and Fukushima. I think people need to know how detrimental nuclear energy is and how it is killing people, whether it's in a power plant, or a bomb, or other things. For me, personally, I think it's very unstable, and sadly, we all know now it has been developed into weapons of mass destruction.

Bullen: You have dealt with uranium in your work. Hollowing Earth (2016-2017) has uranium of course, and then you've looked at The Blue Danube which is a series of glass bombs.

Yhonnie Scarce, Blue Danube 2015. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Scarce: Not far from Woomera is Olympic Down mine, which is a uranium and copper mine, and that's on my Country, Kokatha Country. Hollowing Earth refers to uranium being dug up and how much sickness it causes and how much sickness it causes to the Country too. The bush bananas I've used in that work were at first accidentally burnt through creating the gaping holes in the body of those pieces. I was thinking, "No, this is exactly what it wants to do, so let's just let it happen.'

When you dig up that ground, and you dig out everything that that land has to offer, it starts to die, and it's never going to come back.

That work is a representation of the Country dying.

Yhonnie Scarce, Hollowing Earth 2016-17. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Yhonnie Scarce, Hollowing Earth 2016-17. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Bullen: If you turn the lights down you'll see that glow [from the uranium]. In the cover of darkness, that's when it's most visible.

When you harm land you harm us as well because there is an intimate connection between those two things. I think one of the really poignant things about your work is that you ask people very obviously to understand that connection and to care about that. That really for me comes through in that work.

I want to go back just a little bit to some of the places you visited. Those trips would have been incredibly difficult. How do you feed that back into your practice when you're experiencing trauma as you're visiting those sites?

Scarce: Yes, a large part of making my work is learning or teaching myself how to use that in my work. I’m really conscious about getting it right. If I don't get it right I feel I'm disrespecting my ancestors, and I don't want to upset them because they're the reason I'm here. They're the reason why I'm doing what I do. I don't want to make them appear in a bad way. My work, it's sad but that's the truth.

For hundreds of years since Australia was colonised we have been told to keep our mouths shut and not complain, or get over it. That's what drives me to make these works. I would say I'm digging up the past.

It's easily forgotten by non-Aboriginal people who don't want to acknowledge the past history of the treatment of Aboriginal people and artwork is a perfect way to do that.

Bullen: I feel that's such a thread that runs through your entire practice, there's this beautiful, very visceral idea of care. Daniel Browning [journalist and broadcaster] talked about some of your objects as feeling like they're exhumed body parts, or things that you need to tread very carefully around.

Scarce: Yes, because they're precious. I create those pieces out of love for my people because I want them to be treated with respect.

Bullen: I want to talk a little bit about images. You do use photography in your work, although I would call it extended photography because it's often photography that's deliberately put onto objects of mental memory.

You talked about releasing images from their colonial tethers in the work, Dinah (2016), which is focused on your great grandmother, Dinah Coleman, and in Working Class Man (Andamooka Opal Fields) (2017).

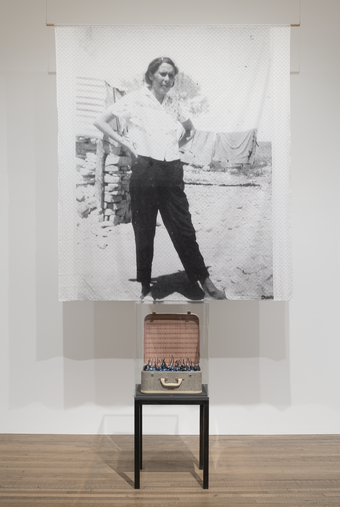

Yhonnie Scarce, Dinah 2016. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Scarce: Yes, with Dinah particularly, that photograph was an ethnographic photograph taken at Koonibba Mission. You don't see it in that work because I didn't want her to be disrespected in any way. Especially in the way that that photograph was originally taken. Her top half was removed. She just had her bottom half of her dress. I worked with my photographer friend, Janelle Lowe, who cropped that image and gave her the dignity that she should have.

I think also there are other images that I've used for other works that Norman Tindale [anthropologist and enthographer employed by Harvard University to ‘study’ Aboriginal communities] had taken as part of his so-called scientific research.

My sister often calls those photographs ‘mugshots’ because they're prison-like images. For me, it was important to celebrate my family through other ways of reinterpreting that image, reclaiming their identity by reworking them.

Granny Dinah, I refuse to let people photograph her while she's on display. It's my role to protect her. I want people to know who she is, but I don't want her to be exposed in a way that people will disrespect her image because that photograph was taken without her permission. Whereas in Working Class Man with my grandfather in it, he was smiling at the photographer.

Yhonnie Scarce, Working Class Man (Andamooka Opal Fields) 2017. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Bullen: For all the hardships that are implied in that image, it is a beautiful image.

Scarce: He's smiling. He's working in extreme heat. He's working with no shoes on hoping that he would make money off opal mining and was always looking for work because it was hard for Aboriginal men in those days to get full-time regular work. They were always on the move. My grandfather was a very quiet man. A quietly spoken man, but very handsome.

It was important to keep all the blemishes in the reproduction of the image, so you can see all the cracks. You can see my mother's tea stain on it.

Yhonnie Scarce, Remember Royalty 2020. Tate and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, with support from the Qantas Foundation in 2015, purchased 2022

Bullen: Let's talk about Remember Royalty. This was one of the largest scales of images that you worked with, placing them on objects.

Scarce: I was asked to make a work for an exhibition that was about the joys of family, Aboriginal life, our humour. The curator, Hannah Presley, and I talked quite a lot about how I would say-- in terms of when we were talking about travelling, I felt like my family were always with me, and a lot of the artworks that I create travel internationally with me as well. I get the chance to show them the world, even though they're not physically here anymore.

That work was about celebrating them and acknowledging their involvement in my career as an artist and introducing them as royalty because I consider Aboriginal people Australia's royalty.

For me having significant members of my family on display was important, to have them created on such a scale that they were never looked down on. People were going to be looking up at them. In order to do that, I worked with a printmaking studio here in Melbourne and spent some time with them discussing the role of each image and who was in it, and the gifts that I was going to create for them.

Yhonnie Scarce, Remember Royalty 2020. Tate and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, with support from the Qantas Foundation in 2015, purchased 2022

Yhonnie Scarce, Remember Royalty 2020. Tate and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, with support from the Qantas Foundation in 2015, purchased 2022

The work is about me thanking them as well. Granny Melba, who is the largest out of the four photographs, she's my great-grandmother. She's 18 in the photograph.

French linen is the material that her photograph is printed on. My grandmother, Fanny really liked beautiful bedding. If she wasn't going to have a nice house or whatever, she would have the best bedding. She's wearing a floral shirt in that photograph, so I went looking for something with tiny flowers.

And then Papa Willy, who was a shearer and he's in the centre of that photograph. I chose a vintage blanket, which might have been made around the same time that he was shearing those sheep.

Yhonnie Scarce, Remember Royalty 2020. Tate and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, with support from the Qantas Foundation in 2015, purchased 2022

Then the family photo is Granny Melba at 13 with her parents and her siblings. That was taken at Koonibba Mission and has been printed on an Actil sheet that was gifted to my great-great-grandparents, her parents, and then in the trunk, a number of spheres for each child in the photograph.

Initially I was thinking of making them toys, but then when I was looking at the spheres, they look like planets. They have the horizon line, they have stars and Papa Willy has a toolbox with the yams in it, his tools of culture, but there's brand new tools inside it.

My grandmother has a French suitcase with gloves from myself, vintage gloves, Actil sheet and a handkerchief, and then all the little bush plums are the grandchildren she didn't get to meet because she died quite young. Granny Melba has a necklace of yams because she wears a crucifix.

Bullen: It's really moving to me that there's now something that has been bestowed upon them which may never have necessarily been bestowed upon them in their lives.

Scarce: Yes, because they had so much taken from them and that's why I say I wouldn't be here if it wasn't for them.

Bullen: There's this increasingly complicated relationship with the UK and its monarchy, and I think this particular work is quite timely. When UK audiences see this work, what are you hoping they will respond to, or how do you hope they might feel? Particularly with royalty in the title. It's so loaded.

Scarce: I'd like them to think about how Australia was colonised by England. That idea of terra nullius, Terra Australis, that this Country was unoccupied, but it was actually occupied by thousands of people and people who fought for Country. They're the actual royals.

Bullen: There are lineages that are thousands of years old, as much as any other monarch, really.

Scarce: I think people need to know that and audiences at Tate need to know that, that there were all these people here and we are still here. Unfortunately, we're not treated that way. The way Australia was colonised was that, again, we were the primitive people that shouldn't exist here, and yet we do and we are. That's why I called it Remember Royalty. I was like, "They're my royalty and they're your royalty. They need to be acknowledged as such."

Bullen: You've had a number of different really significant public art projects. How do you see that fitting in with your broader practice?

Scarce: Well, I think it's become part of it now. I've always been interested in architecture and how buildings or places can tell a story. I think in particular with the former Soviet Union architecture, it's interesting because that's a whole new kettle of fish. Public art is just as important as something that I might create for the gallery space. With the work that I created in collaboration with Edition Office for the NGV Architecture Commission, In Absence, that was really a big moment for me as an artist to create something so tall and strong and powerful.

Yhonnie Scarce, In Absence 2019. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Bullen: You won the Victorian Architecture Award with that one, didn't you?

Scarce: Yes, and Dezeen as well, that was a global award for a small project. I think it has a really powerful way of engaging the public in a different setting. The beauty of public art is that you can really scale it up and it can become monolithic. That's what happened with In Absence. Its intention was not to be a memorial, it was about, again, acknowledgement of the existence of Aboriginal people and creating a space for people to feel welcomed and warm and safe.

Yhonnie Scarce, In Absence 2019. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Yhonnie Scarce, In Absence 2019. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Even though it's this big black structure... it can engulf you, as soon as you walk in you don't know if there's a doorway behind you or an exit. It was telling a story about how there's these smoking trees and structures that smoked eels that still exist that people may not even recognise.

The scar trees that you see that would've been used to make canoes and things that might sit on a main road or on a highway, and how Aboriginal people cared for Country and only took from that land what they needed. They never took any more than that. I think it was interesting to watch people interact with that work because it was a quiet place, even though it was at the back of the NGV International in the garden. You'd sit there and you'd see planes flying across and the clouds going by.

Bullen: There's a real sense of dislocation in that work. Some of that intent is about dislocating people out of their comfort zone as well.

Scarce: Definitely, and it makes you actually look up instead of forward. You have to look up. I think for me that was a really successful way to create a space for not only Aboriginal people, but for non-Aboriginal people who wanted to learn something about us and maybe hopefully go looking for further information, or maybe keep an eye out for a smoking tree that might just be around the corner.

This infrastructure, still exists. It's still operating. You think of Budj Bim in western districts of Victoria, it's now protected under UNESCO because there are eel traps and stone houses that were built thousands of years ago.

Bullen: Similar to public monuments in some ways. That was not their intention, but they become these monumental sites of significance.

Scarce: That people, like myself, would travel thousands of kilometres to visit, just to see what they're doing and what they look like and how they would feel being inside or outside one of them.

Bullen: You've gone through the Soviet Union and other places where there's that brutalist concrete architecture which acts as propaganda. In converse to that, your works act as ‘monuments of care’ and are a way of enacting care. This is more a reaching out or an offered embrace.

Scarce: Also to say, “Come closer.” Those monuments and those buildings that I saw in former Yugoslavia, amazingly rigid but engaging with their concrete curves and colourful mosiacs.

It'd be good to return and see more of them because they're an interesting archive. They are keepers of knowledge. That's how I see In Absence as well. The conversations that people have inside In Absence, they're retained in the walls because that work is listening.

Yhonnie Scarce, Not Willing to Suffocate 2012. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne

Bullen: Something I think about a lot as an Aboriginal curator is that, in all the things we talk about, in the work that we do, we are all inevitably centered in that narrative of trauma and histories. How do you protect yourself within that? Your work is about care, but how do you enact self-care in that space?

Scarce: Well, sometimes I'm not very good at it. I do need to go back home. Reground and then, because I've got connections to the Nullarbor and stuff, it's like I don't just come from the desert, I come from the sea. Being near water but not necessarily in it is important.

Sometimes I'd like to go for a swim, but I don't get the opportunity because I live in Melbourne and because I travel extensively. I have made a promise to myself that I go back to Ceduna at least once a year, but also return to Woomera. It's like when you've got 360 views of the sky at night and the sight line that goes on forever, that's important. And to have silence. I think silence in my head is important for me. That's my self-care.

You can have massages and all these other things, but I think there's nothing like being out bush and without your phone in reception and without your computer and then you're just talking to people. That's it. That's important to me.

Bullen: What are you most proud of in your practice?

Scarce: I'm very proud that I am a glassblower. Not many people can do it. It's a very particular medium. It does take a lot of time to learn how to do it properly. I think being able to exhibit internationally and to take my work overseas, I'm really proud of that. When I went to art school, I had no idea what I was doing. My career has taken me by surprise.

Bullen: What do you hope endures?

Scarce: Well, I guess it's to make change, and to keep our stories alive. In the end, it's not about me. It's the artworks that I want people to be able to continue to see when I'm 80. Hopefully, by then there will be other Aboriginal artists working in glass.

Also with my work, I hope that in 50 years time, young kids or even just people my age will say, "I remember that story," or "I read that in a book."

Bullen: You want the story to endure.

Scarce: Yes, definitely. The artwork will always be there. Like glass, it's at times indestructible, but when it's not, it still remains.

*The word Country is capitalised throughout this interview. For Aboriginal communities, the notion of Country refers to custodianship, care and connection to specific locations. It also refers to vast tracts of land through which particular story, song and kinship lines connect communities. Country is perceived not just as a place but as a concept, which embodies families, language and culture.

Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor