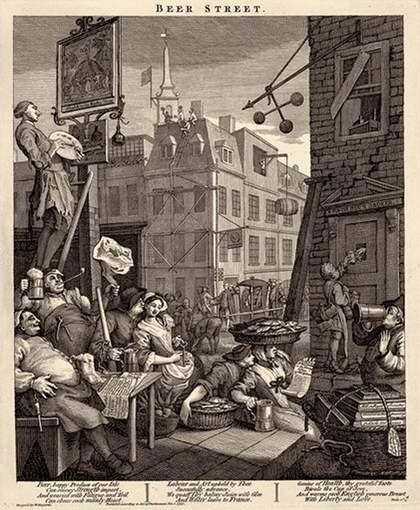

Installation shots of the William Hogarth display marking the 250th anniversary of his death, Tate Britain, 27 October 2014 – 26 April 2015

Hogarth first gained recognition painting scenes from the theatre. He went on to make his name with his darkly humorous ‘modern moral’ series depicting the declining fortunes of foolish or ignoble characters, and brought similar vivacity to the polite interiors of his ‘conversation piece’ portraits. In 1735 he founded an academy for artists and later wrote a treatise on the aesthetic theories he developed over the course of his career. Whether painting, printmaking or writing, he was concerned with forging and defending a distinctly British art.

In 1951 Tate mounted the first major exhibition of Hogarth’s work since 1814. Tate gained independence from the National Gallery in 1955 and started acquiring works in its own right, and further exhibitions and displays followed reflecting research into Hogarth’s life and art. From the early 1950s Tate also acquired work by earlier British artists, allowing Hogarth to be seen in the context of his predecessors: an innovative champion of British art, but by no means the first British artist.

The following essay, ‘Hogarth at the Tate’ by Tim Batchelor, was originally published to coincide with BP Spotlight: William Hogarth 1697–1764 (October 2014 – April 2015), a display at Tate Britain marking the 250th anniversary of Hogarth’s death. The display included almost all of his paintings in the Tate collection, as well as prints, drawings and rarely seen items from the Tate Library and Archive, such as the Engravers’ Copyright Act (1735), Hogarth’s Analysis of Beauty (1753) and Churchill’s Epistle to William Hogarth (1763).

William Hogarth

The Painter and his Pug (1745)

Tate

Introduction

William Hogarth (1697–1764) died at his house in Leicester Fields during the night of 25 October 1764. He had been ill for over a month and after going to bed that night, ‘was seized with a vomiting, and rang his bell with such violence that he broke it, and expired about two hours afterwards in the arms of Mrs Mary Lewis, who was called on his being taken suddenly ill.’

His body was taken back to Chiswick, west of London, where he lived with his wife Jane, and buried close to the Thames in the cemetery of St Nicholas’s Church. A tribute to the artist appeared in the London Evening Post on 28 October ascribing to Hogarth,

the utmost force of human genius, an incomparable understanding, an inflexible integrity, and a most benevolent heart. No man was better acquainted with the human passions, nor endeavoured to make them more subservient to the reformation of the world, than this inimitable artist. His works will continue to be held in the highest estimation, so long as sense, genius and virtue, shall remain among us; and whilst tender feelings of humanity can be affected by the follies and vice of mankind.

In the centuries since his death Hogarth has continued to be a major figure in the history of British art. As one of the earliest native-born British artists of note who gained huge popular appeal for his satirical portrayal of eighteenth-century British society, he has often been referred to as the ‘father’ of British art. Yet despite Tate being founded as the national gallery of British art, works by Hogarth were not on display at Millbank for the first twenty years of its existence.

When pictures by him were transferred to Tate from the National Gallery after the First World War, however, they became the earliest works on display at Tate and remained so for the next thirty years. Hogarth became the starting point for the story of British art, reinforcing his patriarchal status.

As one of the most important British artists, his representation in Tate’s collection has grown over the years and includes some of his most iconic images – though this is mainly limited to his activities as a painter, and not as an engraver and print publisher.

Important exhibitions and displays of his work have been held at Millbank, both at the old Tate Gallery and the new Tate Britain, as his life, work and place in British art continue to be reassessed and celebrated.

Collection and Display: National beginnings

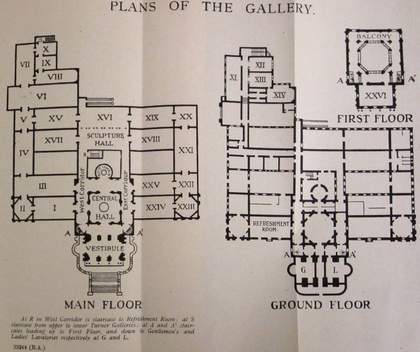

Plan of Tate Gallery in 1914, taken from National Gallery, British Art: Catalogue with Descriptions, Historical Notes and Lives of Deceased Artists, Tate Library and Archive

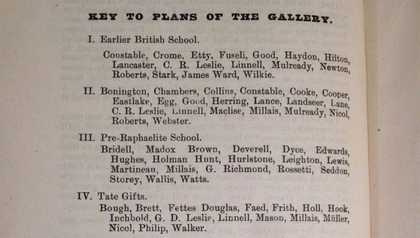

Key to the Plans of the Gallery, taken from National Gallery, British Art: Catalogue with Descriptions, Historical Notes and Lives of Deceased Artists, Tate Library and Archive

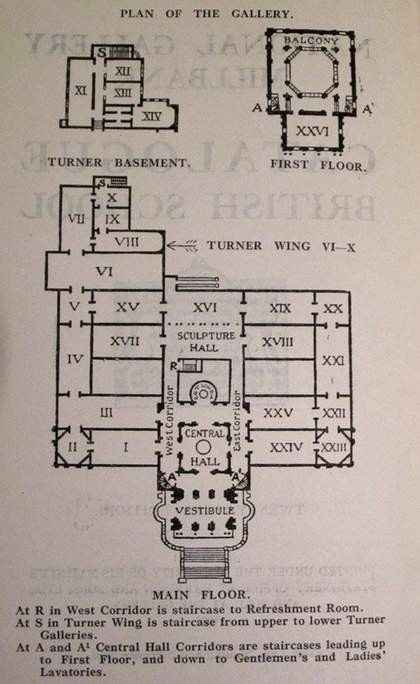

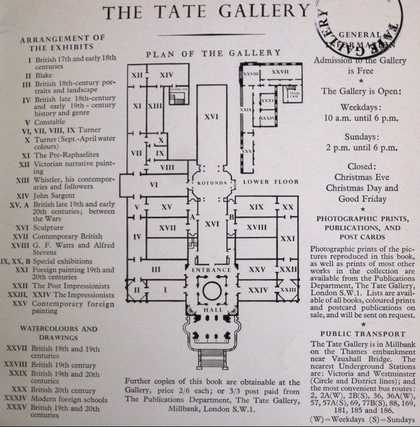

Plan of Tate Gallery in 1924, taken from National Gallery, Millbank – Catalogue, British School, Tate Library and Archive

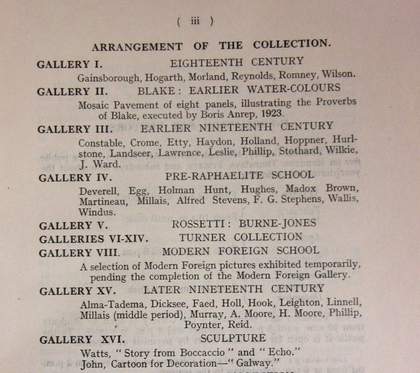

Arrangement of the Collection, taken from National Gallery, Millbank - Catalogue, British School, Tate Library and Archive

The Tate Gallery at Millbank was officially opened by the Prince of Wales on 21 July 1897, with the public opening occurring over three weeks later on 16 August. Despite its official title of the National Gallery of British Art, it was more specifically a gallery of modern British art. The collection and initial displays were based on the collection of Sir Henry Tate (1819–1899), who contributed 65 of the 245 pictures on view. These were modern and contemporary British paintings and sculpture, by artists such as the Pre-Raphaelite painters Sir John Everett Millais (1829–1896) and John William Waterhouse (1849–1917).

Other pictures on display were acquired by the Chantrey Bequest, the fund for purchasing contemporary British art administered by the Royal Academy, and paintings were also sent to Millbank from the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square, who had taken on responsibility for the new gallery. The National Gallery decided that only ‘modern’ British pictures should be considered, defined as works by artists born after 1790.

Thus, two of the leading figures of British art, J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) and John Constable (1776–1837), were not to be included (though a few Constables were allowed to give the gallery a good start). The opening of the new Turner wing in 1910 to accommodate paintings from the Turner bequest remedied this situation, and there were also earlier works by David Wilkie (1785–1841) and Henry Fuseli (1741–1825) on display. But for the first twenty years of the existence of the Tate there were no paintings in the collection or on display dating before 1790.

A plan of the gallery from 1914 shows the first room of the displays as the ‘Earlier British School’ but contained works by the nineteenth-century artists Constable, Crome, Etty, Fuseli, Good, Haydon, Hilton, Lancaster, C.R. Leslie, Linnell, Mulready, Newton, Roberts, Stark, James Ward, Wilkie. Anomalously, works by William Blake (1757–1827), a slightly earlier artist, were displayed in a separate gallery.

It was only after 1915 and the submission of the Curzon Report that the situation was addressed. In his analysis of the national collections Lord Curzon recommended that the Tate should take responsibility for housing modern foreign paintings and historic British art in addition to the modern and contemporary British painting it already contained, and proposed a rationalisation of the collecting policies pursued by the Tate, National Gallery, Victoria & Albert Museum and The British Museum.

This resulted in the transfer in 1919 of over two hundred historic British pictures from the National Gallery to the Tate, including the first works by Hogarth: The Beggar’s Opera; Benjamin Hoadly; Lavinia Fenton; Sigismunda; and the Marriage A-la-Mode series. Whilst three seventeenth-century pictures were transferred as well (two portraits by Cornelius Johnson and Girl with a Parrot c.1670 by Peter Lely), it was the paintings by Hogarth that formed the starting point for the displays in room 1 of the Tate Gallery.

This remained the case for the next thirty years – British art as displayed at the Tate, founded as the National Gallery of British Art, began with Hogarth.

Collection and Display: An independent Tate

Plan of Tate Gallery in 1958, taken from A Brief History of the Tate Gallery with a Selection of Paintings and Sculpture, Tate Library and Archive

The initial transfers made in 1919 remained the sole representation of Hogarth at the Tate until after the Second World War when further transfers were made.

In 1949 The Staymaker was transferred to Tate, but the following year Marriage A-la-Mode was returned to the National Gallery. This iconic series of paintings returned to Tate briefly in 1960–1 and 1963–4, but after that remained in Trafalgar Square where it can still be seen today.

In 1951 the second major transfer of works by Hogarth was made from the National Gallery to Tate, with five paintings moved over to Millbank: The Strode Family, James Quin, Mrs Salter, The Painter and his Pug, and O the Roast Beef of Old England (‘Calais Gate’). Hogarth’s large conversation piece, The Graham Children, was also transferred the following year.

As with the Curzon Report, these transfers coincided with the moment when the constitution of the national galleries was being considered, culminating in the National Gallery and Tate Gallery Act of 1954 in which the Tate became legally separated from the National Gallery as an independent institution. Further transfers from the National Gallery around that time made sure that the right pictures were in the right gallery, with more sixteenth and seventeenth-century pictures entering the Tate collection. This, combined with the acquisition of early British pictures in the 1950s meant that Hogarth would no longer form the starting point in the story of British art in the displays at Millbank.

The guide to the Tate Galley from 1951 shows that the first gallery now displays seventeenth- and early-eighteenth century pictures, with works by Cornelius Johnson (1593–1661), Sir Peter Lely (1618–1680), and Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) preceding those by Hogarth and his contemporaries, whilst in the entrance hall and staircase hung seventeenth and eighteenth-century portraits, as well as Tudor and early Stuart portraits lent by Mr Francis Howard and Group Captain Loel Guinness.

Two remaining works were transferred from the National Gallery in 1960: Heads of Six of Hogarth’s Servants and The Shrimp Girl. This was the same year that the Marriage A-la-Mode series returned to Tate, though only for a year. In the event, The Shrimp Girl went back to Trafalgar Square with it, making a brief return in 1963–4 before remaining there.

The final work to be transferred from the National Gallery was the portrait of Thomas Pellet M.D., sent to Millbank in 1972 having entered the collection of the National Gallery that year following a Deed of Gift made in 1959.

In 1964 Norman Reid succeeded John Rothenstein as Director of the Tate and organised a re-hang of the displays. Works by Hogarth were gathered into room 2, the small hexagonal room with the mosaic floor which is often referred to as the Blake room, forming a monographic representation of Hogarth there for many years.

William Hogarth

Ashley Cowper with his Wife and Daughter (1731)

Tate

The newly independent Tate Gallery acquired its first work by Hogarth in 1965. This was the conversation piece of Ashley Cowper with his Wife and Daughter, signed and dated 1731, which was bought at auction at Sotheby’s on 24 November 1964 by Agnew on behalf of Tate.

Another work entered Tate’s collection a few months later in the following year, Satan, Sin and Death, purchased from Sabin Galleries. Three further paintings have been purchased by Tate since then: Thomas Herring in 1975, having been lent to Tate from a private collection since 1968; The Dance in 1983, also having been lent since 1968 by the South London Gallery; and the oil sketch Head of a Lady, the last work bought by Tate in 1994.

To mark the centenary of Tate in 1997, the two small portraits of the Ranby children were presented as gifts to the gallery from a private collection, and in 2003 Three Ladies in a Grand Interior (‘The Broken Fan’), having been accepted by H.M. Government in lieu of tax, was allocated to Tate – the most recent work to enter Tate’s collection.

In 1984 the National Gallery requested the return of five important British pictures, which it argued were required for display in the context of Old Master European painting at Trafalgar Square. The list included An Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump by Joseph Wright of Derby and the large conversation piece by Hogarth, The Graham Children, which had been at Tate since 1952.

The two institutions had formed an agreement in 1954 that the National Gallery had the right to claim any work that had entered either collection prior to 1954, though this was superseded by the 1954 Act which had created an independent Tate and made it clear that any transfers must be made by consultation and agreement.

But the Tate felt that the National Gallery had a moral claim on the pictures and did not want to jeopardise relations, so the works were eventually returned in 1987. As Francis Spalding notes in her history of the Tate Gallery,

there is no doubt that the loss of the Hogarth and the Wright, in particular, seriously impoverished the Tate’s representation of eighteenth-century art.

Collection and Display: A partial view

William Hogarth

A Rake’s Progress (plate 4) (1735)

Tate

The representation of Hogarth in Tate’s collection is primarily through his painting. This reflects the recommendation of the Curzon Report of nearly a hundred years ago, regarding the rationalisation of the collecting remits of the national galleries. The consequence of this is that the national museums collected by medium, rather than by artist.

The national collection of prints and drawings is held at The British Museum, and so was not part of Tate’s official collecting remit. For a figure such as Hogarth, for whom printed works were a major aspect of his artistic career, this has significant implications on how he could be represented at Tate. By being able to only see his paintings, the visitors to Tate Britain get only a partial view of the artist.

Yet despite these clearly defined collecting remits, works on paper by Hogarth have entered Tate’s collection. There are currently fourteen prints by Hogarth in the collection, as well as another eight prints after Hogarth, notably by artists such as William Blake and Thomas Rowlandson. How these works came to be in the collection and their early provenance is unclear. Because Tate did not officially collect prints, these were originally held in the ‘reference collection’.

They were only transferred into the main collection in 1973, when Tate was preparing for the transfer of the holdings of the Institute of Contemporary Prints and the establishment of a formal print collection in 1975. Their early designation shows how their status was at odds with the main purpose of Tate’s collection. Works on paper entering the collection following 1973 have a recorded provenance which these earlier prints lack.

Without any acknowledged collecting policy with regard to works on paper, strategic or otherwise, the prints form a rather random and incomplete impression of Hogarth as a graphic artist. This is best exemplified by the modern moral series of A Rake’s Progress, a narrative series of prints that show fateful moments in Tom Rakewell’s life scene by scene. Tate’s collection has six out of the eight prints, missing plate two and plate six, and so cannot tell the complete story.

The other iconic ‘modern moral’ series of A Harlot’s Progress and Marriage A-la-Mode are not represented at all, and whilst the Tate has a copy of the important print Gin Lane it does not possess the accompanying print of Beer Street.

Many of these prints were until recently in a very poor state, often with severe stains, numerous tears, folds and frayed edges. This meant that they were unexhibitable and remained in the stores of the Prints and Drawings Room in the Clore Gallery. Only in the past few years have the works been looked at again and treated by the paper conservators at Tate.

A few remain to be conserved, but many of them are now in a much better condition and can be considered for display for the first time in decades. However the representation of Hogarth as a graphic artist in Tate’s collection remains an area that needs to be addressed.

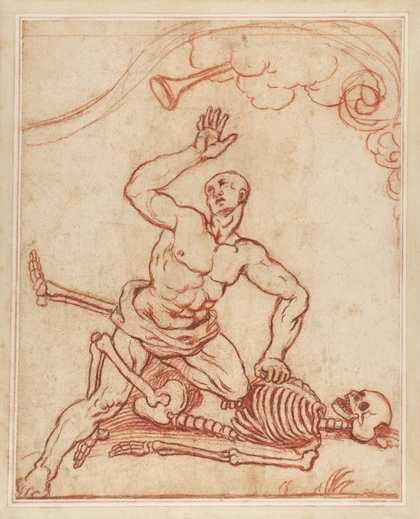

William Hogarth

George Taylor Triumphing over Death (c.1750)

Tate

In addition to the prints Tate’s collection also has four drawings by Hogarth. All four entered the collection as part of the Oppé Collection, the important collection of over three thousand works on paper assembled by Paul Oppé and acquired by Tate in 1996.

Three of the four works are red chalk drawings, designs for the tombstone of the bare-knuckle boxer and Champion of England, George Taylor; the fourth a pen and wash sketch of a lady and child.

Collection and Display: Former Hogarths

Before the development of more sophisticated Hogarth scholarship paintings were often erroneously attributed to Hogarth. This may have been because they had the slight appearance of a Hogarth, or were from the right period, or were attributed to him in the absence of knowledge of other artists working contemporary to him. The well-known and established painter was often an easy hook on which to hang works which were not necessarily by the artist.

Though they are no longer considered works by Hogarth, there are a number of works in Tate’s collection which at one time were attributed to him.

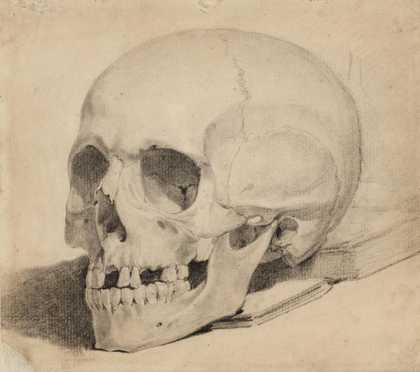

Unknown artist, Britain

Study of a Human Skull (?c.1750)

Tate

In 1892 the Reverend John Gibson presented two works on paper to the National Gallery, both attributed to William Hogarth and transferred to Tate in 1919. Study of a Human Skull ?c.1750 (N02220) retained its attribution until 1947. This may have been because of its chance resemblance to the skull painted by Hogarth in scene 3 of Marriage A-la-Mode: The Inspection, which is shown resting on the table on the far left of the composition. However, the attribution to Hogarth was subsequently deemed incorrect, and the nationality of the possible artist even called into question.

The second drawing as part of the gift, Study of a Man’s Head ?c.1765 (N02221) has an inscription on the back of it which reads:

The person who gave this Drawing assures me that it was bought of Mrs Hogarth – that it was her Husbands Portrait and done by himself. It seems to be in the bold style of his Engravings.

Yet it does not appear to represent Hogarth or to be produced in his style, and the identity of the artist remains unknown.

Self-Portrait of an Unknown Artist at the Age of Twenty-two ?c.1740 (N01076) was sold at Christie’s on 9 June 1866 as ‘Hogarth. Portrait of a gentleman, in a black dress and cap.’ This attribution did not last long and when the painting was next sold thirteen years later, at Christie’s on 30 May 1879, it was re-attributed to William Aikman as a portrait of a boy. It was bought by the National Gallery at that sale, but re-attributed again and catalogued as a self portrait by Hamlet Winstanley. This attribution also failed the test of time and the artist remains unknown.

Nathaniel Hone

Mary Hone, the Artist’s Wife (?1760)

Tate

The portrait of Mary Hone, the Artist’s Wife by Nathaniel Hone c.1760 (N00675) was bequeathed to the National Gallery in 1861 as a portrait by Hogarth of his sister Mary. As noted by Elizabeth Einberg in her catalogue entry for the work, this was probably due to a misinterpretation of a near illegible inscription on the painting. The portrait was transferred to Tate in 1919 as a Hogarth and included in an article by R.B. Beckett, ‘Portraits of Hogarth’s Family’ (Connoisseur, September 1948). It was reattributed to Nathaniel Hone by Elizabeth Einberg in 1979, after comparisons with known portraits by Hone of his wife, such as the oval painted portrait of her which he includes in his own self portrait (National Gallery of Ireland, NGI.196).

Another picture formerly attributed to Hogarth is An Elegant Company Playing Cards c.1725, now attributed to Gawen Hamilton (T00943). This painting is one of three known versions, all of which have since their early histories been associated with Hogarth and the family of his father-in-law, the painter Sir James Thornhill (1675–1734). The Tate version was sold at Christie’s on 23 November 1951 as by Hogarth. One early theory for the painting, attributing it to Hogarth and its association with the Thornhill family, was that it may have been painted by the artist to make amends for his secret marriage to Sir James’s daughter which took place in 1729. However, in stylistic terms it does not fit with Hogarth’s oeuvre and appears closer to the conversation pieces by the Scottish artist Gawen Hamilton (1723–1798). Elizabeth Einberg in her catalogue entry for the painting (The Age of Hogarth, Tate Gallery 1988, no.15) also examines the painter Dietrich Ernst André (c.1680–1734?) as a possible candidate.

Egbert Van Heemskerk III

The Doctor’s Visit (c.1725)

Tate

The painting The Doctor’s Visit c.1725 by Egbert van Heemskerk III (T00808) had appeared for sale at Christie’s on 12 October 1956 catalogued as ‘Hogarth: The Death Bed’. It come onto the market again a few years later at an untraced sale at Philips where it was bought by ‘Claudio Corvaya’, a pseudonym used by the art critic Brian Sewell. He was working at Christie’s around this time and using an assumed name allowed him to buy works at auction incognito. The painting was subsequently sold by Sewell at Christie’s in November 1965 where it was bought by Oscar and Peter Johnson Ltd, from whom it was purchased by the Tate. It was included as a Hogarth in the 1971 Hogarth exhibition at the Tate curated by Lawrence Gowing (no.12) as an example of Hogarth’s early painting but was reattributed by Elizabeth Einberg to Egbert van Heemskerk III in the mid 1980s. As she notes in her catalogue entry for the picture (The Age of Hogarth, Tate Gallery 1988, no.164),

The earlier attribution of this painting to Hogarth was partly based on his affinity for low genre and his possible borrowings from Heemskerk’s engraved scenes, as already pointed out by Antal (1962). … The tendency to attribute low genre scenes to Hogarth was already noted by J.T. Smith , who wrote in 1829, that “Mercier, Van Hawkin [Van Aken], Highmore, Pugh, or that drunken pot-house Painter, the younger Heemskirk, who was a singer at Sadler’s Wells” were all painters whom the unwary tended to confuse with Hogarth.

Exhibitions and Displays

In addition to the display of works by Hogarth in the main collection, the artist has been the subject of a number of special exhibitions at Tate.

The first of these was in a period revival for the gallery immediately following the Second World War. The Tate was the main venue for exhibitions in a London short of space for such shows, which were mostly organised by the British Council and the newly formed Arts Council of Great Britain.

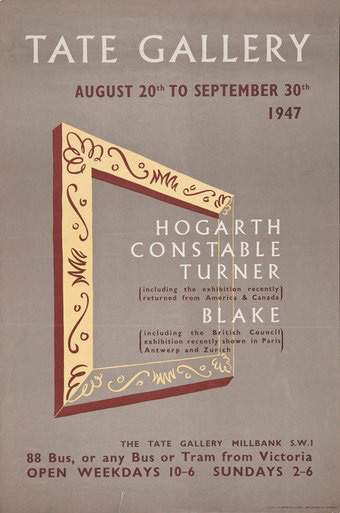

One of the most successful shows was the exhibition Masterpieces of English Painting – Hogarth, Constable, Turner, organised by the Tate, National Gallery and Victoria and Albert Museum as a touring exhibition and shown at the Art Institute of Chicago, 15 October – 15 December 1946.

It subsequently toured to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (closing there on 16 March 1947) and the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada (2 April – 11 May 1947) where it received a total of 76,575 visitors, the most for an exhibition since the gallery had opened in 1926.

Poster for the exhibition Masterpieces of English Painting – Hogarth, Constable, Turner, Tate Library and Archive (TG 106-11)

The show retuned to London for display at the Tate from 20 August – 30 September 1947. It proved so popular that it was extended for a month, closing on 30 October 1947.

The Court Circular noted a visit to the exhibition by Queen Mary on 2 October, a short report in the Daily Telegraph the following day stating that,

Queen Mary spent over two hours looking at the special Hogarth, Turner and Constable exhibition. Incidentally, I hear it has been a great success. Attendances have averaged well over 5,000 daily.

By the 1 October over 135,000 visitors had been recorded, a remarkable figure in an age before the so-called ‘blockbuster’ exhibitions. The exhibition of Hogarth, Constable and Turner coincided with a British Council exhibition, also at Tate, of works by William Blake which had recently returned from a tour of continental Europe.

There was also a display of watercolours by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, as noted in the review, ‘Five British Artists’, by Eric Newton in The Times on 24 August 1947. Reflecting the prevailing attitude to British art at this time, he states that,

The Tate Gallery has never contained better evidence of the Britishness of British art than it does at present – Hogarth, Blake, Rossetti, Constable and Turner make an impressive series of names. They could have been produced only by a country with a strong literary tradition, a shamelessly romantic temperament and an amateurish but zealous attitude to the craft of painting.

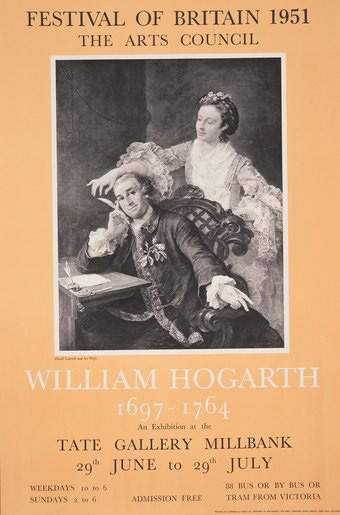

Poster for the William Hogarth exhibition at the Tate Gallery, 1951, Tate Library and Archive (TG 106-29)

Four years later in 1951 the Tate hosted the first solo exhibition of the work of Hogarth at the gallery, and the first monographic show on the artist since the one held at The British Institution in 1814. Open for one month, from 29 June to 29 July, it was organised by the Arts Council of Great Britain as part of the Festival of Britain. In his Foreword to the catalogue, Philip James, Art Director at the Arts Council, gave his reasons for choosing Hogarth to mark this event:

For the Festival of Britain the Arts Council is concentrating primarily on British Art, both of the present and the past. The choice of Hogarth to represent the Old Masters seems an appropriate one, especially so since, although in many senses he might be called a popular artist, no major single exhibition of his work has been held for the past 136 years. Hogarth is not only the first great native English easel-painter; his pictures epitomize perhaps more than any other the British character.

Curated by R.B. Beckett, the show contained 71 catalogued works, the first 13 being works on paper (a few of which were multiple works). The review in the Guardian (20 July 1951) was positive, calling the exhibition ‘a fine tribute to a Londoner of genius’, though it noted the absence of the painted modern moral series. A Rake’s Progress remained at the Sir John Soane Museum in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and Marriage A-la-Mode had been returned to the National Gallery the previous year.

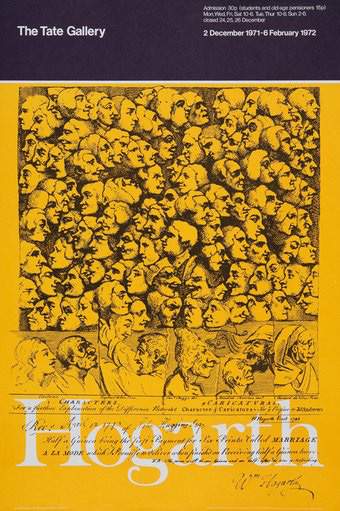

Poster for the Hogarth exhibition at Tate in 1971, Tate Library and Archive (TG 106-155)

It was a gap of exactly twenty years to the next Hogarth exhibition, held at the Tate Gallery from 2 December 1971 – 6 February 1972. It was curated by Lawrence Gowing, a former Keeper of British Art at Tate who was subsequently Professor of Fine Art at the University of Leeds, and comprised a total of 222 catalogued works.

The exhibition built on recent Hogarth scholarship, particularly the work of Professor Ronald Paulson, which had examined the life and career of the artist in much greater depth than previously, especially his activity as a printmaker, and positioned him within the context of his time. In his Foreword in the exhibition catalogue Norman Reid, Director of the Tate, noted that although Hogarth was one of the greatest English painters he had always been,

[a] rather awkward figure to cope with in the context of British art as a whole. In fact for some years now at the Tate Gallery he has been carefully isolated in a room of his own, albeit in his correct historical sequence and usually with every one of his pictures in the collection on view. At the same time his appeal to an audience far wider than the normal art-loving public has perhaps made him slightly suspect to the connoisseur and aesthete.

Installation shot from the Hogarth exhibition at Tate in 1971, Tate Library and Archive

At this time Tate did not have a dedicated exhibition space and used the Duveen Galleries for such shows. These large cavernous spaces, the central spine of the gallery today, were designed for the display of sculpture and required the construction of temporary walls and ceilings with lighting track to create the exhibition space.

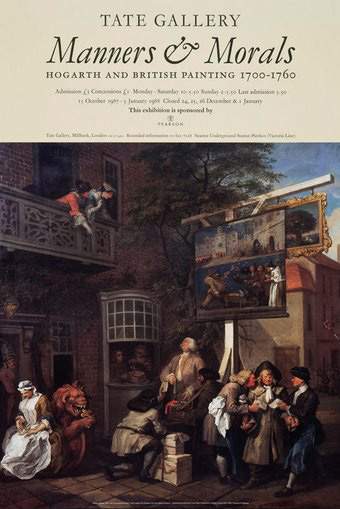

Poster for the Manners & Morals exhibition at Tate in 1987, Tate Library and Archive (TG 106-273)

In 1987 Elizabeth Einberg, Assistant Keeper of the British Collection at Tate and Hogarth scholar, curated the exhibition Manners & Morals – Hogarth and British Painting 1700-1760. The press release for the show indicates a different title - initially it was called Pomp, Virtue and Decorum - and the announcement goes on to say,

[t]he period lies comfortably within the lifespan of England’s first great native painter William Hogarth (1697-1764) whose response to and reactions against the prevailing canons of pomp, virtue and decorum in art did so much to set the artistic tenor of the period.

Though the title changed, the essence of the exhibition remained: a survey show of the period with Hogarth at its core. As noted by Marina Vaizey in her review of the show in the Sunday Times (18 October 1987), ‘Hogarth, naturally, is the star, although he was not so regarded in his lifetime.’

Installation shots from Manners & Morals exhibition at Tate in 1987, Tate Library and Archive

Hogarth was represented by 35 paintings, much more than any other artist in the show. These included iconic works such as the portrait of Thomas Coram and the Election series, but also a few works which were not included in the 1971 exhibition, such as Horace Walpole aged 10 and the portraits of Hannah Ranby and George Ranby.

It was held in the purpose-built exhibition space occupying the north-east quadrant of the gallery, which had been designed by Richard Llewelyn Davies and opened in 1979.

Ten years later Elizabeth Einberg also curated the small exhibition Hogarth the Painter, held at the Tate Gallery from 4 March – 8 June 1997 to mark the 300th anniversary of the artist’s birth. The Tate paintings formed the bulk of the display with twenty works, the other eleven coming from important UK and Irish collections including The Royal Collection, the National Gallery and some private collections. These included works not shown in the previous Hogarth exhibitions, such as the portraits of George Parker, 2nd Earl of Macclesfield and an Unknown Gentleman in Grey, Holding Gloves, and displayed six paintings which were, in effect, new to Hogarth literature.

Installation shots from the exhibition Hogarth the Painter at Tate in 1997, Tate Library and Archive

The year 2000 saw the birth of Tate Britain, as the Tate Gallery was renamed and reformed back to its original purpose as the National Gallery of British Art, with Tate Modern down the river at Bankside housing the modern foreign collection.

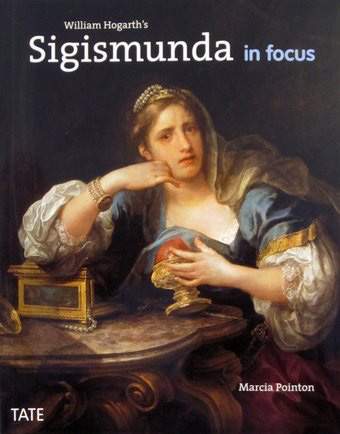

Cover of the book accompanying the display on Hogarth's Sigismunda at Tate Britain 2000, Tate Library and Archive

The new Director of Tate Britain, Stephen Deuchar, instigated a series of ‘in focus’ displays which aimed to ‘cast a fresh light on British works from the Tate Collections.’

The first of these was William Hogarth’s Sigismunda in focus, a one room free display examining one of Hogarth’s most controversial paintings.

Shown from 24 July – 4 November 2000 it was curated by Marcia Pointon, Pilkington Professor of Art History at Manchester University, described by Deuchar as, ‘one of the most vital forces in British art history for more than two decades.’

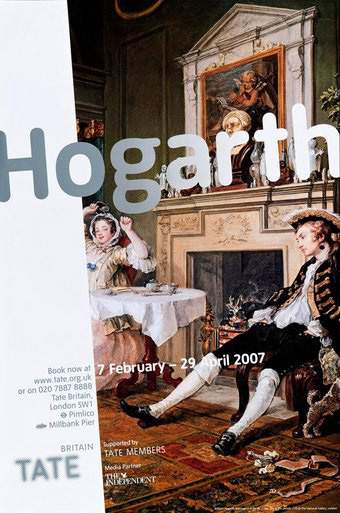

Poster accompanying the Hogarth exhibition at Tate Britain in 2007, Tate Library and Archive (TG 106-444)

The display was related to her Paul Mellon Lectures which were held at Tate Britain in the autumn of 2000, the title of the series being Brilliant Effects: Jewellery and its Image in English Visual Culture 1700-1800.

The third major Hogarth retrospective was held at Tate Britain in 2007. Curated by Christine Riding, Curator of Eighteenth and Nineteenth-Century British Art at Tate Britain, and Professor Mark Hallett of the University of York, the exhibition opened at the Musée du Louvre, Paris (18 October 2006 – 7January 2007) before its display in London at Tate Britain (7 February – 29 April 2007). It then travelled toSpain for display at Caixa Forum, Barcelona (30 May –26 August 2007).

The show was originally intended to be the first exhibition at the new Caixa Forum gallery which was being developed in Madrid (as indicated in the exhibition catalogue), but the revised completion date meant it was shown in their space in Barcelona instead. The tour to Paris and Barcelona marked the first major representation Hogarth in France and Spain.

Installation shots from the Hogarth exhibition at Tate Britain in 2007, Tate Library and Archive

In his foreword to the catalogue Stephen Deuchar referred back to the observations of his predecessor Norman Reid in 1971 that Hogarth was a rather awkward figure in the context of British art. Deuchar noted how in the generation since then the artist had become less ‘suspect’, and that,

he seems today to have become naturally reintegrated within narratives of British art, not least because of the recent revolution in art history which has led us to think it normal, rather than eccentric, to consider works of art in intimate relationship to the complexities of the particular social world in which they were originally created.

Held in the Linbury Galleries (part of the Tate Centenary Development and opened in 2001), the exhibition was a huge success attracting a total of 176,859 visitors – placing it in the top ten exhibitions held at Tate Britain since it was launched in 2000.