The representation of Hogarth in Tate’s collection is primarily through his painting. This reflects the recommendation of the Curzon Report of nearly a hundred years ago, regarding the rationalisation of the collecting remits of the national galleries. The consequence of this is that the national museums collected by medium, rather than by artist.

The national collection of prints and drawings is held at The British Museum, and so was not part of Tate’s official collecting remit. For a figure such as Hogarth, for whom printed works were a major aspect of his artistic career, this has significant implications on how he could be represented at Tate. By being able to only see his paintings, the visitors to Tate Britain get only a partial view of the artist.

Yet despite these clearly defined collecting remits, works on paper by Hogarth have entered Tate’s collection. There are currently fourteen prints by Hogarth in the collection, as well as another eight prints after Hogarth, notably by artists such as William Blake and Thomas Rowlandson. How these works came to be in the collection and their early provenance is unclear. Because Tate did not officially collect prints, these were originally held in the ‘reference collection’.

They were only transferred into the main collection in 1973, when Tate was preparing for the transfer of the holdings of the Institute of Contemporary Prints and the establishment of a formal print collection in 1975. Their early designation shows how their status was at odds with the main purpose of Tate’s collection. Works on paper entering the collection following 1973 have a recorded provenance which these earlier prints lack.

Without any acknowledged collecting policy with regard to works on paper, strategic or otherwise, the prints form a rather random and incomplete impression of Hogarth as a graphic artist. This is best exemplified by the modern moral series of A Rake’s Progress, a narrative series of prints that show fateful moments in Tom Rakewell’s life scene by scene. Tate’s collection has six out of the eight prints, missing plate two and plate six, and so cannot tell the complete story.

The other iconic ‘modern moral’ series of A Harlot’s Progress and Marriage A-la-Mode are not represented at all, and whilst the Tate has a copy of the important print Gin Lane it does not possess the accompanying print of Beer Street.

Many of these prints were until recently in a very poor state, often with severe stains, numerous tears, folds and frayed edges. This meant that they were unexhibitable and remained in the stores of the Prints and Drawings Room in the Clore Gallery. Only in the past few years have the works been looked at again and treated by the paper conservators at Tate.

A few remain to be conserved, but many of them are now in a much better condition and can be considered for display for the first time in decades. However the representation of Hogarth as a graphic artist in Tate’s collection remains an area that needs to be addressed.

William Hogarth

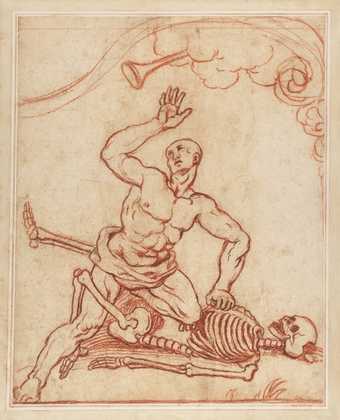

George Taylor Triumphing over Death (c.1750)

Tate

In addition to the prints Tate’s collection also has four drawings by Hogarth. All four entered the collection as part of the Oppé Collection, the important collection of over three thousand works on paper assembled by Paul Oppé and acquired by Tate in 1996.

Three of the four works are red chalk drawings, designs for the tombstone of the bare-knuckle boxer and Champion of England, George Taylor; the fourth a pen and wash sketch of a lady and child.