Before the development of more sophisticated Hogarth scholarship paintings were often erroneously attributed to Hogarth. This may have been because they had the slight appearance of a Hogarth, or were from the right period, or were attributed to him in the absence of knowledge of other artists working contemporary to him. The well-known and established painter was often an easy hook on which to hang works which were not necessarily by the artist.

Though they are no longer considered works by Hogarth, there are a number of works in Tate’s collection which at one time were attributed to him.

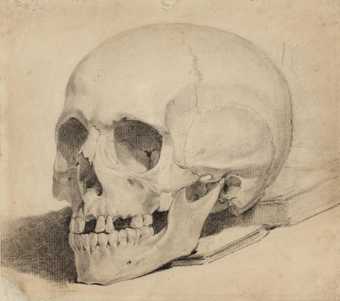

Unknown artist, Britain

Study of a Human Skull (?c.1750)

Tate

In 1892 the Reverend John Gibson presented two works on paper to the National Gallery, both attributed to William Hogarth and transferred to Tate in 1919. Study of a Human Skull ?c.1750 (N02220) retained its attribution until 1947. This may have been because of its chance resemblance to the skull painted by Hogarth in scene 3 of Marriage A-la-Mode: The Inspection, which is shown resting on the table on the far left of the composition. However, the attribution to Hogarth was subsequently deemed incorrect, and the nationality of the possible artist even called into question.

The second drawing as part of the gift, Study of a Man’s Head ?c.1765 (N02221) has an inscription on the back of it which reads:

The person who gave this Drawing assures me that it was bought of Mrs Hogarth – that it was her Husbands Portrait and done by himself. It seems to be in the bold style of his Engravings.

Yet it does not appear to represent Hogarth or to be produced in his style, and the identity of the artist remains unknown.

Self-Portrait of an Unknown Artist at the Age of Twenty-two ?c.1740 (N01076) was sold at Christie’s on 9 June 1866 as ‘Hogarth. Portrait of a gentleman, in a black dress and cap.’ This attribution did not last long and when the painting was next sold thirteen years later, at Christie’s on 30 May 1879, it was re-attributed to William Aikman as a portrait of a boy. It was bought by the National Gallery at that sale, but re-attributed again and catalogued as a self portrait by Hamlet Winstanley. This attribution also failed the test of time and the artist remains unknown.

Nathaniel Hone

Mary Hone, the Artist’s Wife (?1760)

Tate

The portrait of Mary Hone, the Artist’s Wife by Nathaniel Hone c.1760 (N00675) was bequeathed to the National Gallery in 1861 as a portrait by Hogarth of his sister Mary. As noted by Elizabeth Einberg in her catalogue entry for the work, this was probably due to a misinterpretation of a near illegible inscription on the painting. The portrait was transferred to Tate in 1919 as a Hogarth and included in an article by R.B. Beckett, ‘Portraits of Hogarth’s Family’ (Connoisseur, September 1948). It was reattributed to Nathaniel Hone by Elizabeth Einberg in 1979, after comparisons with known portraits by Hone of his wife, such as the oval painted portrait of her which he includes in his own self portrait (National Gallery of Ireland, NGI.196).

Another picture formerly attributed to Hogarth is An Elegant Company Playing Cards c.1725, now attributed to Gawen Hamilton (T00943). This painting is one of three known versions, all of which have since their early histories been associated with Hogarth and the family of his father-in-law, the painter Sir James Thornhill (1675–1734). The Tate version was sold at Christie’s on 23 November 1951 as by Hogarth. One early theory for the painting, attributing it to Hogarth and its association with the Thornhill family, was that it may have been painted by the artist to make amends for his secret marriage to Sir James’s daughter which took place in 1729. However, in stylistic terms it does not fit with Hogarth’s oeuvre and appears closer to the conversation pieces by the Scottish artist Gawen Hamilton (1723–1798). Elizabeth Einberg in her catalogue entry for the painting (The Age of Hogarth, Tate Gallery 1988, no.15) also examines the painter Dietrich Ernst André (c.1680–1734?) as a possible candidate.

Egbert Van Heemskerk III

The Doctor’s Visit (c.1725)

Tate

The painting The Doctor’s Visit c.1725 by Egbert van Heemskerk III (T00808) had appeared for sale at Christie’s on 12 October 1956 catalogued as ‘Hogarth: The Death Bed’. It come onto the market again a few years later at an untraced sale at Philips where it was bought by ‘Claudio Corvaya’, a pseudonym used by the art critic Brian Sewell. He was working at Christie’s around this time and using an assumed name allowed him to buy works at auction incognito. The painting was subsequently sold by Sewell at Christie’s in November 1965 where it was bought by Oscar and Peter Johnson Ltd, from whom it was purchased by the Tate. It was included as a Hogarth in the 1971 Hogarth exhibition at the Tate curated by Lawrence Gowing (no.12) as an example of Hogarth’s early painting but was reattributed by Elizabeth Einberg to Egbert van Heemskerk III in the mid 1980s. As she notes in her catalogue entry for the picture (The Age of Hogarth, Tate Gallery 1988, no.164),

The earlier attribution of this painting to Hogarth was partly based on his affinity for low genre and his possible borrowings from Heemskerk’s engraved scenes, as already pointed out by Antal (1962). … The tendency to attribute low genre scenes to Hogarth was already noted by J.T. Smith , who wrote in 1829, that “Mercier, Van Hawkin [Van Aken], Highmore, Pugh, or that drunken pot-house Painter, the younger Heemskirk, who was a singer at Sadler’s Wells” were all painters whom the unwary tended to confuse with Hogarth.