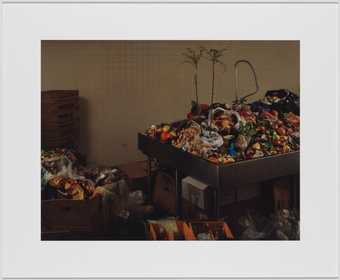

I am Taryn Simon, and we are installing A Living Man declared Dead and Other Chapters at Tate Modern. It was produced over a four year period in which I travelled around the world recording bloodlines and their related stories. And in each of the 18 chapters you see the external forces of territory, governance, power, religion, colliding with the internal forces of psychological and physical inheritance. The works are attempting to map the relationships among chance, blood and other components of fate; trying to see or struggling to find some sort of code or pattern embedded within that. The chapters are constructed through three parts, the first being a portrait panel which systematically orders the members of a specific bloodline. Then a text panel, which provides corresponding information in list form, and then there is a third panel which I call the Footnote Panel, and it includes images that represent fragments of the overall story, sometimes documents or personal effects, and the beginnings of other stories.

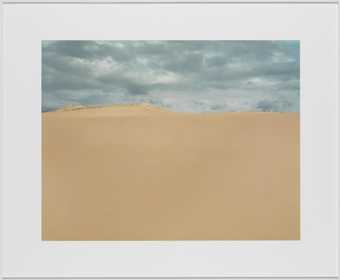

The portraits themselves are always photographed on this background of the non-place, this neutral cream background that eliminates any races, any environment or context. There is almost a periodic table effect in the way that they are laid out, and it’s extremely ordered. And then the Footnote Panel introduces a certain entropy. There is a more abstract and less absolute configuration, whereas the portrait panels are very specifically ordered, and something that I can’t edit or curate; it is a specific, determined line. And the work does seek to look at stories and individuals as past’s future and future’s past, and these ideas of repetitions and even that we are all sort of ghosts of another time and a time to come.

Chapter One was produced in Utah Pradesh, India. I documented a bloodline in which four members of the bloodline are actually listed as dead. Family members tried to interrupt the hereditary transfer of land by declaring other members dead so they could seize their land. So in that, I am actually photographing individuals who on paper do not exist; and photography being the greatest proof of life, there is this strange irony between that. I was interested in the metaphor established in that work as something that can refer to the entire work. We are all steadily heading towards death.

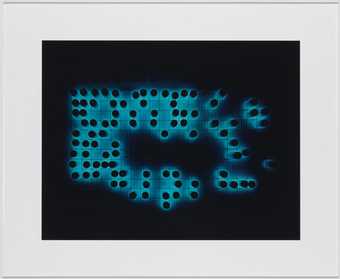

In Australia, in 1859 the rabbit was introduced and the population exploded, and the government has continually been trying to produce diseases to control the rabbit population. So here you see a government-controlled experiment in which all of these rabbits have been injected with a lethal disease, and they are waiting to see if it will be an effective population control method. So since the taking of those photographs, all those rabbits have died.

And then in the Footnote Panel you see a chocolate bilby which Hays Chocolate, in collaboration with the Foundation for Rabbit Free Australia, has been eliminating the production of Easter rabbits in chocolate and replacing that with the Easter Bilby to popularise an animal that they are comfortable with keeping alive, because they want the public to be more comfortable with killing the rabbit. It is this view of an experiment, and the idea that experiments have been something that we all participate in, perhaps with our knowledge, or without.

There is an ordering principle in all of the works, where they are scientifically ordered, where it is the eldest member of a generation followed by their descendants, and then their descendants, and it repeats and so on. And in the piece in Lebanon, when you arrive at this one man named Robarbo Dodini, he is both the youngest member of a line… but then he also becomes the eldest member of that line, because he is a member of the Druze, and he and his family believe that he is the reincarnation of his grandfather. Therefore when you arrive at him, the pattern repeats because he is both his father’s son, and his father’s father. So the pattern keeps going and going and going. It also tries to consider this idea that we keep going, people keep being produced. And does that all amount to some sort of evolution, or are we on repeat?

I don’t know that there is an answer. It’s kind of this relentless cycle that just keeps going, and people are born and people die, and the stories keep coming and coming. It’s kind of this unending machine-like churning out of stories and individuals, and to what end is completely unknown. I guess I’m trying to organise it for myself!