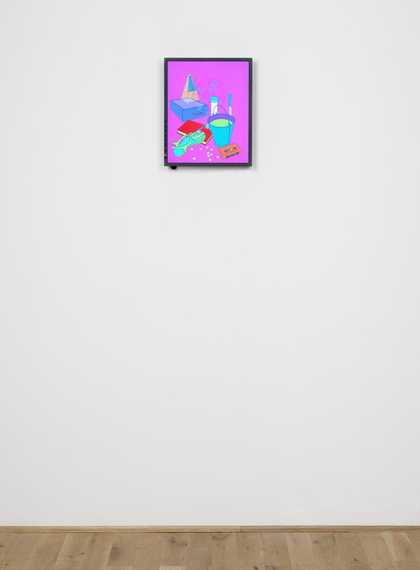

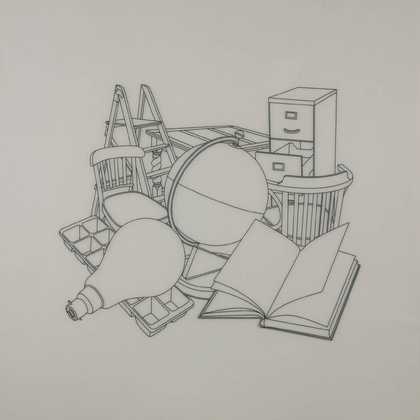

When I first started, in my early work, I didn’t want to be defined by a particular way of working, so what I ended up doing was, I would do a group of works that were boxes, a group of works that were balances, a group of works with found objects, a group of works that were neons. So there were little bodies of work with big language changes between them, or form changes between them. But to me, the way in which I thought about art, and thought about making art, hasn’t changed very much at all. So that in the Boxes I did something which I’ve done, say, in the recent paintings, which is you set up a system that takes you somewhere, and if you follow the rules, it takes you some place, but you can’t predict what it is. All I did was cut the lids and then reverse them, and yet something more than what I did has come out of what I’ve done. An Oak Tree is a glass of water on a glass shelf, and it’s always placed on a wall about nine feet high, just out of reach. So you can see it, but you can’t touch it. And then there is a text that accompanies it. I needed the text because I didn’t want it to simply be a name change. If I called it an oak tree and that was it, you think it’s just a thing, and he’s called it this, and what I was trying to do in the text was explain that it isn’t just the name I’ve changed. I’ve changed the actual object. The Oak Tree was meant to be ‘how do I create the maximum imaginable transformation?’ and my way of doing it was to produce no transformation at all. This is something that other artists like Duchamp did. It’s something that in the Sixties and the early Seventies when I did the Oak Tree, there were lots of artists thinking about this question of what is the base level for art – what is the fundamental thing in art? In the painting Knowing, I’ve taken a series of objects and none of them overlap. Each one of them is defining its own little area of space, and so all the objects are related in their spatial character, but it’s not a painting in which there is perspective in the sense of a singular perspective to which all the things are conforming. The smallest objects are at the front, where in a painting, if you have small objects that are big, that means they are close. That’s the language of paint. That’s how we understand a painting. All of these things are things that we do, because of our understanding about how to read a painting, how to read an image. I’m not interested in objects, I’m not interested in consumerism, I’m not interested in design. I’m interested in language and the way in which we interpret the world, understand the world, through the things we make. And so there’s the things we make, and then I use those as images, which is another thing we make, and then it’s my language, and I’m trying to play in that zone, where there is some slippage between things. I’m trying to create slippage. And one of the things that I have found by keeping the language of the images going for as long as I have, is that now I am able to do the diversity of things because I’ve got the consistent language. It’s the consistent language that is allowing me to do giant installations, postage stamps, paintings. I can do these things because of the language, and so in a way I am much closer to where I wanted to be in the beginning than I ever expected.