Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt

Love and the Pilgrim (1896–7)

Tate

Edward Burne-Jones is considered by many to be the last of the Pre-Raphaelites. His work reflects the ideals of the end of the nineteenth century. Known mainly as a painter, there was much more to Burne-Jones than you might realise.

He combined the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelites with Aestheticism and Symbolism to create a style that is as mesmerising as it is complex. Perhaps not as well known as his Pre-Raphaelite contemporaries, Burne-Jones was a celebrated name in Victorian England. As a man of many talents, there are many ways we can remember his legacy.

1) The Painter

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt

Frieze of Eight Women Gathering Apples (1876)

Tate

Burne-Jones was raised by his father after his mother died in childbirth. He never intended to be a painter. He had ambitions to go into the Church and become a minister. Settled on his future, he began a theology degree at Oxford University. Life, however, had a different plan for Burne-Jones.

At Oxford, he met William Morris. They shared an interest in the Medieval, in art and in poetry. They became close friends. Morris would later become a major figure of the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain. It was with Burne-Jones that Morris set up his textiles company, Morris & Co. which continues to operate today.

Returning together from a trip to France, Burne-Jones and Morris made a momentous decision to devote their lives to art. Morris wished to become an architect and Burne-Jones a painter. Burne-Jones travelled to London and sought an apprenticeship with the Pre-Raphaelite painter and poet, Dante Gabriel Rossetti. It was there he learnt the skills that would launch his career. Much of Burne-Jones’s earlier work echoes the shadowy allure of Rossetti’s style.

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

Phyllis and Demophoön 1870

Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

In 1864, Burne-Jones was elected to the prestigious Society of Painters in Water-Colours. As he experimented with his style, the Society began to disapprove of his heavy layering of colour. They preferred paintings to be light and translucent. Burne-Jones paid no attention. In 1870, he painted Phyllis and Demophoӧn. The painting caused a scandal, because it showed full-frontal male nudity. The Society asked him to add some drapery, but Burne-Jones refused. He left the Society and withdrew from public life for the next seven years. He called this time his most blissful, because it was when he could paint free from the pressures of deadlines for exhibition or public expectation.

Through his friendship with Rossetti and the art critic John Ruskin, Burne-Jones became associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Starting out as an artist his work absorbed their desire for realism and aimed to be true to nature. His paintings often portray the Pre-Raphaelite traditional figure of a pale skinned woman with red hair. Members of the Brotherhood would use many of the same models. Fanny Cornforth, Rossetti's model and lover, also modelled for Burne-Jones.

2) The Storyteller

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

Love Among the Ruins 1870-1873

Private Collection

Like many within the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Burne-Jones was fascinated with stories. The poems of his contemporaries inspired many of his paintings. Love Among the Ruins, one of his most celebrated paintings, take its title from the poem of the same name by Robert Browning. Browning’s poem tells of two lovers who find each other in the ruin of a once great city. Burne-Jones used the moment of their reunion as the subject of his painting.

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

The Rose Bower 1886-90

The Farringdon Collection Trust

Burne-Jones was also interested in fantasy. While William Morris became a vocal advocate for socialism, Burne-Jones chose to remove himself from society and reality. He found solace in fiction. The Legend of Briar Rose series is one of his most famous sets of work. These four large panels (and ten small joining panels) depict a moment from the fairytale of Sleeping Beauty. Later Burne-Jones's work would inspire J R R Tolkein, who attended the same school in Birmingham as the painter. Tolkein would go on to write The Lord of the Rings and would cite Burne-Jones and Morris as influences.

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

The Doom Fulfilled 1888

Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart

Like filmmakers who adapt novels, Burne-Jones was the Victorian equivalent who transformed tales into spectacular visuals. Ancient myths particularly interested Burne-Jones. Arthur Balfour, the future Prime Minister, commissioned Burne-Jones to create a series based on the Greek myth of Perseus. The ten paintings tell of Perseus’s quest to kill the monster Medusa and rescue Andromeda. Burne-Jones was so zealous, Balfour had to alter the room by blocking off windows and changing doors for the paintings to fit. The task was so aspirational though that Burne-Jones was unable to finish the commission.

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt

The Golden Stairs (1880)

Tate

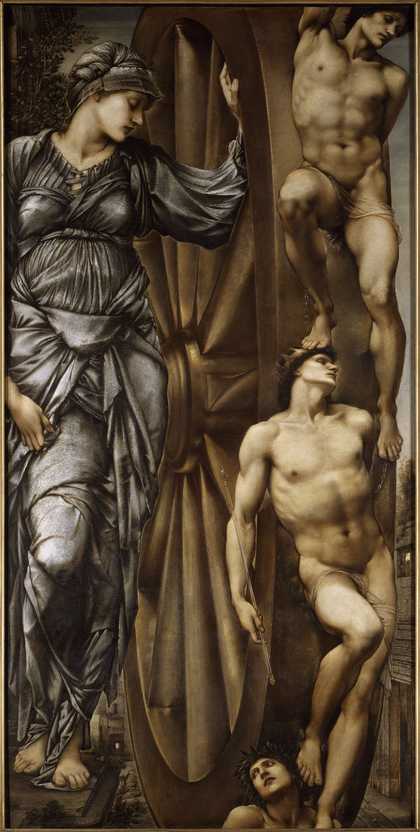

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

The Wheel of Fortune 1883

Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt

King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid (1884)

Tate

3) The Joker

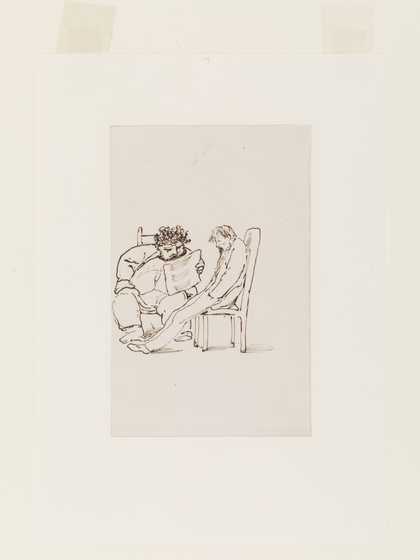

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

William Morris reading poetry to Edward Burne-Jones 1861

Victoria & Albert Museum

You might not think of Burne-Jones as a practical joker, but this was how he was seen by his friends. Burne-Jones and Morris both shared a love for the Medieval and for the poetry of Tennyson. Their friendship was also founded on humour. Jokes were often made at Morris’s expense. Burne-Jones would, in the Topsy Cartoons, create caricatures of himself and Morris. While he was tall and slender, Morris was short and stout and he would emphasise these differences in his drawings.

Burne-Jones enjoyed making fun of Morris’s weight, which he knew he was insecure about. One night, he sewed Morris’s waistcoat tighter while he slept. In the morning, Morris thought that he had gained weight. While most of these were jokes between friends, there was also a sense of rivalry. Perhaps, Burne-Jones was jealous of his talented and successful friend.

He saw Morris as a clown. He often told the story of when Morris became trapped in a suit of armour. Burne-Jones also made a series of little wombat sketches. The facial features and obese body resembled Morris. Jokes seemed to be a hallmark of their friendship.

4) The Designer

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

The Beguiling of Merlin 1872-77

National Museums Liverpool, Lady Lever Art Gallery

Burne-Jones spread his artistic vision from painting to other art forms. He was a partner at Morris & Co. The company specialised in carving, stained-glass, paper-hangings and carpets. In 1891, he was elected a member of the Art Workers Guild. Five years later, Morris & Co received their largest commission. Burne-Jones was tasked with designing tapestries that would decorate the dining room at Stanmore Hall. The figures were based on the Quest for the Holy Grail, an Arthurian legend about a goblet that provides happiness, infinite youth and wealth.

Burne-Jones enjoyed revisiting the Medieval legend of Arthur. He was able to marry his love for design with his passion for storytelling. In 1894, he designed the costumes and sets for Henry Irving’s production of King Arthur at the Lyceum Theatre. Irving was a patron of Burne-Jones’s work. While the artist was unhappy with the end result of his work, it brought to life the settings of his paintings. He also designed jewellery such as brooches. The designs reflected the Medieval style of his paintings.

5) The Devotee

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt. & William Morris

The Adoration of Magi 1894

Manchester Met University

While his paintings might capture our attention, Burne-Jones was actually renowned for his designs for stained-glass. Today, you can travel around the UK and see some of Burne-Jones’s finest works in churches. In his hometown of Birmingham, the Cathedral is adorned with stained-glass windows by Burne-Jones. They retell Biblical stories of the Nativity, the Crucifixion and the Last Judgement. Perhaps most famously, the ‘green dining room’ at the V&A features work by Burne-Jones. Elsewhere, All Saints Church in Wilden contains windows designed by Burne-Jones, as does St Martin's Church in Brampton.

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

The Good Shepherd 1857-1861

Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Even though he abandoned his theology studies, religion still played a huge part of Burne-Jones’s artistic output. Between 1889 and 1916, five books by different ministers were published that examined the Christian iconography within Burne-Jones’s work. His stained-glass windows were seen as an example of what Christianity should stand for in the modern age. One reason why Burne-Jones became less popular was due to a rise in secularism. Many had hoped that Burne-Jones’s evocative aesthetic would inspire church-goers. On his death, the Christian press mourned his loss and praised his pious imagination.

As a Pre-Raphaelite, Burne-Jones moved away from glorifying religion. He felt it distanced the viewer from understanding God’s message. By portraying Biblical stories with realism, he made religion relatable and accessible. He felt he could convey this through his paintings, rather than through the study of theology. Art was accessible to all. Theology, on the other hand, was reserved for the scholar and couldn’t inspire the masses.

6) The Portraitist

Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

Portait of Margaret Burne-Jones, 1885-6

Private Collection

Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

Portait of Madame Deslandes, 1895-6

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia

Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

Portait of Amy Gaskell, 1893

Private Collection

As well as the lavish paintings of myth and legend that he was famous for, Burne-Jones also painted portraits. These were often personal studies of significant women in his life. He would only accept commissions to paint portraits if they came from close friends or important people in his circle. Smaller in size and more intimate, these portraits were a chance to explore real emotion, moving away from the fantasy of his other work.

Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt.

Portait of Georgiana Burne-Jones, 1883

Private Collection

One of his most famous portraits depicts Georgiana MacDonald, his wife, and their two children Philip and Margaret. MacDonald was an essential figure in Burne-Jones’s life. She was a woodcut artist and an avid pianist. When Burne-Jones had an affair with Greek model Maria Zambaco, Macdonald remained his wife. She did, however, became closer with Morris. The two shared a mutual interest in politics and social liberalism. Morris’s wife was also having an affair with Rossetti, so the two found themselves in similar circumstances.

This portrait of McDonald conveys Burne-Jones’s feelings towards his wife. Painted long after his affair, McDonald is shown holding book of flowers open at the page for pansy (also known as ‘heartsease’), symbolising undying love. The composition of the portrait and way she is posed, slightly to the side with her arm leaning on a ledge in the foreground, is inspired by portraits of the Italian Renaissance. Though Burne-Jones was unhappy with the portrait it could be said to capture McDonald's personality: her serenity, self-confidence and courage. However, when you compare this with his depictions of daughter Margaret, it is possible to see an emotional distance between him and McDonald in this painting. Her stark features might in some way signify their changing love.

7) The Trendsetter

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt

Sidonia von Bork 1560 (1860)

Tate

During his lifetime, Burne-Jones's paintings were incredibly popular. In 1890, thousands lined up to see The Briar Rose cycle of paintings. He worked closely with fine-art photographer Frederick Hollyer. His photos invited a wider audience to appreicate Burne-Jones's work. Internationally, he became well known after the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. His painting was praised and he was awarded the Légion d’honneur. This world's fair staged Burne-Jones's work to a European audience, with visitors including Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh.

Like his fellow Pre-Raphaelites, Burne-Jones also had a huge influence in fashion. The flowing fabrics and looser waistlines in his paintings influenced modern dress. Morris & Co. created fabric to cater for these new tastes. Stores like Liberty began offering women a chance to dress like the women of a Burne-Jones painting.

After his death in 1898, Burne-Jones fell out of critical favour. 100 years after Burne-Jones's birth, his nephew, the then Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, launched an exhibition at the Tate Gallery. It failed to reinstate Burne-Jones’s reputation in the art world. His style was no longer the trend. Today, however, Burne-Jones’s style is reminiscent of the height of contemporary fashion. The ornate glamour of Burne-Jones's paintings situate him as an influence and reference for fashion designers like John Galliano and Gareth Pugh. There has been a renaissance in the Burne-Jones aesthetic. He is once again the trendsetter he was during his lifetime.