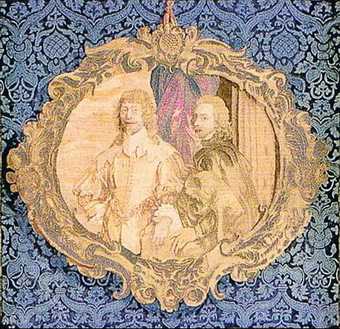

One thing is certain: Sir William Killigrew would have been overjoyed to know that he is now reunited with his wife. When Killigrew commissioned Van Dyck to paint him in 1638, he made sure that a matching portrait was executed of the woman he had married more than a decade earlier, and with whom he had seven children. Later, when financial hardship obliged Killigrew and his wife to live apart, he wrote a heartbroken letter to a friend: ‘All our friends doe knowe that in thirty yeares being Maried we have never had one discontent or anger between us,’ he declared. ‘[I] doe desire nothing in this world more than to have my Wife live [with] me.’

Their separation was only temporary, but the Van Dyck portraits immortalising their love were split up. The paintings have been parted for at least 150 years, and possibly twice that. So Tate should now be congratulated on acquiring them both – Sir William from a British collection last year, and Lady Killigrew at a New York auction in January.

Sir Anthony Van Dyck

Portrait of Sir William Killigrew (1638)

Tate

Sir Anthony Van Dyck

Portrait of Mary Hill, Lady Killigrew (1638)

Tate

The paintings were clearly intended to be seen together, in connubial unity. The aesthetic gain is enormous, too. Viewing them side by side, I realised how adroitly Van Dyck had conducted an absorbing pictorial dialogue between the two images. He makes them enhance each other at every turn, and defines the singularity of each sharply characterised individual even as their overall compatibility is celebrated.

Sir William, a courtier and playwright who enjoyed the patronage of Charles I, appears the epitome of a dreamer, lost in reverie as he leans against a column. His costly satin jacket has a sombre air, even though its expanse of black is slashed in the sleeve, exposing a flamboyant white shirt modelled with all the finesse at Van Dyck’s command. Lips slightly parted, Killigrew might be mouthing lines of dialogue from a play in progress. Van Dyck must have aimed at conveying the pensive power of a man accustomed to writing in his head before committing quill to paper.

His wife, Mary, on the other hand, is far from oblivious of her surroundings. Resplendent in russet, at the furthest remove from her husband’s sober attire, the glamorous Lady Killigrew stares brazenly at the viewer. She seems above all conscious of her audience, unafraid to return our gaze in full measure. While Sir William is tightly buttoned up, hiding his neck in an exquisite white ruff, she discloses a great deal of naked flesh.

Only a few auburn ringlets and a pearl necklace are permitted to interrupt the fashionable pallor of her neck and upper shoulders. Nothing prevents our eyes from following the slope of her right breast down to the point where a nipple is about to be revealed (at the very last moment, Van Dyck ensures that discretion prevails). But Lady Killigrew is supremely aware of her comeliness.

She wants us to share her enjoyment of the blooms in her left hand, which she may have picked on a ramble through the countryside. Lady Killigrew does, after all, seem to emerge from the darkness of a cave. Unlike Sir William, she is set in a wild place where plants sprout from an overhanging rock-face and fierce winds make the distant trees bend and sway. Van Dyck, as if animated by a similar energy, is at his liveliest when handing Mary’s hair. Leaving much of the area around her head free from anything save raw underpaint, he allows the curls to dance with exceptional vivacity around her face. They caress it with an almost flirtatious zest, signalling that Lady Killigrew herself may relish the opportunity to excite the attention of amorous courtiers.

In the end, though, these portraits add up to an affirmation of marriage’s inviolability. Along with her provocative charm, Mary is a wife and mother. The stone ledge inserted in her rural setting has a very specific role to play. It seals her off from us, emphasising that the woman beyond the wall is out of bounds to anyone except her husband. Van Dyck’s sensual response to Lady Killigrew may be overt, and remind us of the debt that Peter Lely would owe to him when painting the far more libidinous beauties of Charles II’s court. But the unabashed wantonness of the Restoration period was very different from Charles I’s court. Elegance prevailed in a court romantically dedicated to a doomed belief in the divine right of kings.

Van Dyck did everything to foster this fantasy in the portraits he concocted with such panache. He painted Charles I and Henrietta Maria as if their marriage really had been made in heaven. And he made sure that, beneath Killigrew’s dreaminess, signs of passion can be detected. His right hand, emerging so prominently from the restless folds of his shirt-sleeve, is notable for its tension. His fingers are unexpectedly splayed, as if Killigrew were gripped by emotions far more forceful and difficult to control than his placid face might suggest. This strength of feeling is confirmed by Van Dyck’s handling of the landscape beyond. Its dominant tree is convulsed by stormy gusts which agitate the clouds beyond as well.

The blustery countryside contrasts with the classical stillness of the architectural setting. It is as if Van Dyck, who would himself die at 42, only three years later, had a premonition of the chaos that overwhelmed Sir William in the following decade. Charles I was beheaded, and under the Commonwealth Killigrew suffered considerable privation. It was probably then that poverty forced him to sell these paintings. In the light of their loss, we cannot help finding a prophetic significance in the ring hanging from a ribbon on Sir William’s funereal jacket.

For it may well mourn the memory of a loved one, and I cannot help noticing that the ring lies next to his heart.

Notes

Sir William Killigrew was accepted by HM Government partly in lieu of tax, and allocated to Tate with additional support from the Patrons of British Art, Christopher Ondaatje and the National Art Collections Fund. Lady Killigrew was purchased with assistance from the National Art Collections Fund and Tate Members. Both go on display at Tate Britain later this year.