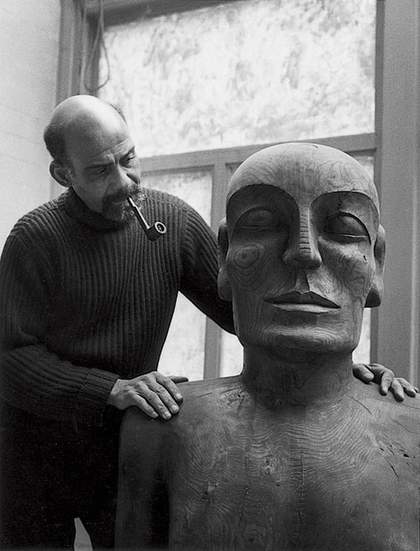

His hands rest lightly on the massive shoulders of his sculpture Johanaan. The great head, carved from elm, stares forward as if into remote space. In a striking photograph of 1963, Val Wilmer pictured the sculptor Ronald Moody in his studio in Fulham with this work which he had made almost thirty years earlier. It is now forty years since Wilmer’s picture was taken, and Johanaan is finally on show as the centre piece of a display of Moody’s wood-carvings at Tate Britain.

The sculpture’s dignified calm and air of permanence is perhaps deceptive. This is the first time that Ronald Moody’s work has been officially recognised as part of the mainstream of British art, although Moody, who was born in Jamaica, spent most of his working life in Britain, up to his death in 1984. Behind the Tate’s exhibition, and its acquisition of Johanaan for the collection, lie the efforts of a number of people, notably Cynthia Moody, the artist’s niece and trustee of his estate, to re-establish the sculptor’s reputation, and, more broadly than this, to pressurise our national art institutions into recognising that the London art scene has long been a much richer and more diverse phenomenon than they have been prepared to acknowledge.

When work by a neglected artist like Moody is put on show we assume it appeared from nowhere, or from total obscurity. But as always there is a history. Moody’s work was in fact recognised and in demand in at least four ‘moments’ in the art of the 20th century. His life story is woven with a cultural currents that are themselves being brought more and more to light.

Moody was born in 1900 in Kingston into a well-off professional family, and he lived there until he was 23. Bowing to his family’s conventional outlook, Moody opted to study dentistry in London and by the mid-30s he was successfully established with a practice near Oxford Circus. However, he had one of those road-to-Damascus revelations, brought about by the experience of seeing the room of ancient Egyptian art in the British Museum and knew he wanted to be a sculptor. He immediately bought some plasticine and began to mould imaginary faces. Continuing with his dentistry for a while, he taught himself to carve. Thus, without any training or academic background, but with a powerful desire to find his own voice, he produced his first carved head in 1935, in oak, which he called Wohin (Whither), from the title of a Schubert song.

This marked his first episode of success. One of the first to notice him was Marie Seton, the writer and biographer of Sergei Eisenstein and Satyajit Ray. She was so impressed by Wohin, ‘this enormous, mysterious head’, that she bought it and became close friends with the artist. Wohin was also seen by Alberto Cavalcanti, the Brazilian documentary film maker, then working in London, who arranged for Moody to have an exhibition in Paris. The success of his work on the continent encouraged Ronald to move to Paris in the late Thirties, and his life might have turned out very differently if the outbreak of the war in 1939 had not changed everything. After escaping from Paris he made an arduous journey through occupied France and across the Pyrenees into Spain. He caught pleurisy on the way, and when he eventually reached England in October 1941, his health was permanently affected.

A number of Moody’s carvings were included in the 1939 exhibition Contemporary Negro Art at the Baltimore Museum of Art in the USA, a large survey show organised by the Harmon Foundation. Among them was his great female head, Midonz 1937. This marked his second scene of recognition. The show was a late expression of the Harlem Renaissance, the flowering of black literature, art, music and performance in New York in the 1920s.

Meanwhile, Moody’s Paris success followed him to London and from 1950 until the early 60s regular London exhibitions brought him a growing presence on the British art scene, a third moment in which his work was recognised. At the same time he was connected to another history. In 1931 Ronald’s brother Harold Moody, who was a doctor, had founded the League of Coloured Peoples in London to combat the racial prejudice and discrimination he had encountered in Britain. Ronald was not interested in political activism but in the mid-1960s he did join the nascent Caribbean Artists Movement, whose important part in British intellectual life has been meticulously re-told in a recent book by Anne Walmsley (The Caribbean Artists Movement (1966-1972), New Beacon Books, 1992). CAM was mainly a writers’ movement, but there were also at this time a number of independent galleries such as Signals and the New Vision Centre which pursued a policy of artistic internationalism in the face of Britain’s fixation on the United States.

His subject was man and woman in search of full human development. Moody was drawn to Egyptian, Chinese and Indian sculptural traditions rather than the Greek.

These activities set the scene for the fourth moment of Ronald Moody’s visibility, the recent past. In the 1970s, the artist Rasheed Araeen, who had arrived from Pakistan in the 1960s, became a tireless campaigner for the recognition of the work of African and Asian artists in Britain since the 1930s, claiming them as part of the mainstream of British society, and not a separate phenomenon of ‘ethnic’ arts. Araeen was eventually able to substantiate this claim in a pioneering exhibition, The other story: Afro-Asian artist in postwar Britain, organised in 1989 with Andrew Dempsey at the Hayward Gallery. Ronald Moody’s work was included.

Along with these radical forms of cultural activity, Moody was long associated with a thoroughly conservative body, the Society of Portrait Sculptors. Here there is a curious paradox. Moody’s portraiture, often commissioned and necessary to his livelihood, was on the one hand the most conventional aspect of his work. But on the other it was a practice which somehow informed or underlay, in a transformed state, the original and most beautiful qualities of his work.

Ronald Moody’s wood-carvings belong to what might be called a category of modernised figuration. They are marked by simplification or stylisation, a form of figuration with symbolic or allegorical overtones. They are marked also by ‘archaicism’, a very important category in 20th century culture, since so much of what we think of as the modern in modern art is directly inspired by the most ancient art. On the other hand Moody hardly touches on abstraction. It appears abstraction had no interest for him. If he was influenced by African art it was not that aspect of African art, which was so important for artists like Picasso or Brancusi : the bold abstraction in the masks of village Africa, whereas Moody was closer to the courtly art of Ife, especially the royal portrait heads. His ignorance of abstraction may account for a certain awkwardnes and literalness when he introduced overt symbols into his ‘portait’ format (as in Hiroshima 1977). He was unable to allow the symbolic to arise from formal experiment – in the way Brancusi did, for example. In Brancusi the symbolic is realised in the form and can’t be discussed separately from it.

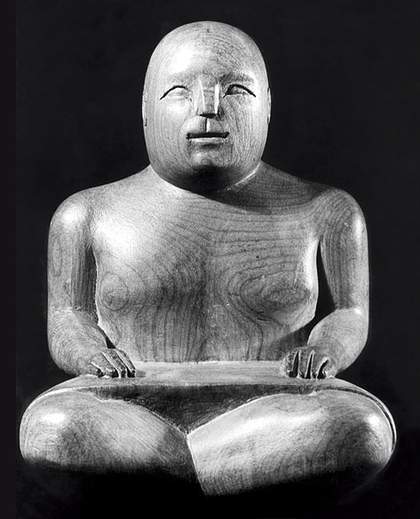

Moody’s carving creates a sort of generalised face, a composite of racial types if you want to see it in that way, or you could see it as a face that belongs to no particular individual and no particular culture or race. Johanaan (1936), besides being called by an archaicised version of a common first name – John – was also at various times called Alles in German, ‘all’, or ‘all people’, and The Human Being as a Living Thing.

He succeeds in creating a Being – not a likeness in the sense of his actual portraits, or a symbol of some abstract quality – but lifelike in another sense, a sort of aspirational being. Marie Seton called it the ‘inner content’. She felt the focal point of Moody’s carvings was ‘man and woman in search of full human development’, and she went on, ‘his psycho-philosophical approach explains why he was drawn to Egyptian, Chinese and Indian sculptural traditions rather than the Greek’.

One of the most distinctive features of Moody’s art is the way he used the grain of the wood. I don’t know of any other modern artist who made such play with the wood-grain. Of course many other carvers were sensitive to it. It was a feature of Henry Moore’s doctrine of ‘truth to materials’, for example. One can imagine Moore carefully selecting or buying wood with this in mind. But Moody’s pieces of wood, singular and vital though they are, seem to have come to him by almost serendipitous means, and often gratis. The oak beam of a cider press, a railway sleeper and a ship’s fender are some of the found objects which lie behind the figures at the Tate.

Moody’s use of the grain seems very personal to him. How much is the fastidiousness around the mouth of the noble and defiant woman Midonz, due to the given expressivity of the lines and cracks in the wood? I believe it was in this way that Moody was able to show the combination of movement and stillness in a single figure that he s much wanted to achieve. The grain provides the mobile energy, the lines of force, that compliment the overall massive stillness of the head.

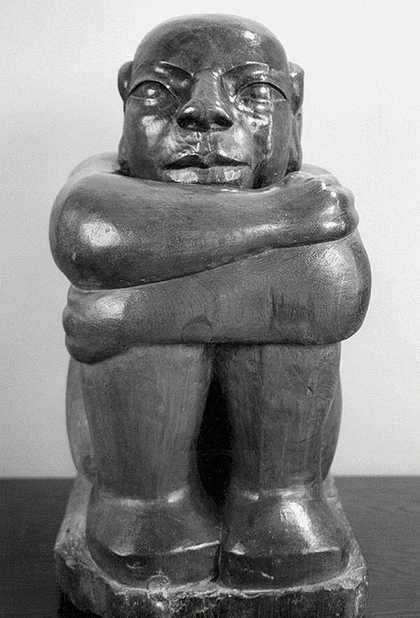

There is one significant exception, both to the symbolic pieces and to the inward-looking heads, and this is The Onlooker 1958. It is Moody’s image of the artist’s role in society. It is as if this figure exhibits the earthiness, the grotesque element, that is absent from the idealised, spiritual images. The spiritual seeker with feet of clay. In Moody’s vision, the artist is both hugging himself as if drawn into his shell, in a self-protective gesture, and looking out, observing. Not a serene figure but one buffeted by life, troubled, willing – or fated – to fall into the muck.

During his lifetime, Moody’s carvings knew many vicissitudes. Midonz was never returned by the Harmon Foundation despite many efforts by Moody, and by Marie Seton, to recover it. He missed it terribly, and he was never to see it again. It was due to an extraordinary piece of detective work by Cynthia Moody that Midonz was tracked down and found, and joins the other carvings in Moody’s show at the Tate.