Piet Mondrian is often seen as a rather distanced character, inhuman even. His paintings don’t appear to be very expressive - and people often say they’re ‘emotionless’ or ‘calculated’. But the years I’ve spent studying his art and his career lead me to be believe that this is far from the truth. Tate Liverpool’s Mondrian and his Studios is the first exhibition to concentrate closely on the artist’s working environment - and curating it has convinced me that, if we look at Mondrian’s practices carefully, we can not only come to a better understanding of him, but we can take a few lessons away ourselves.

1. Follow your heart

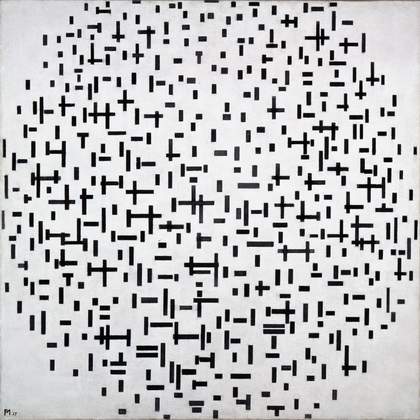

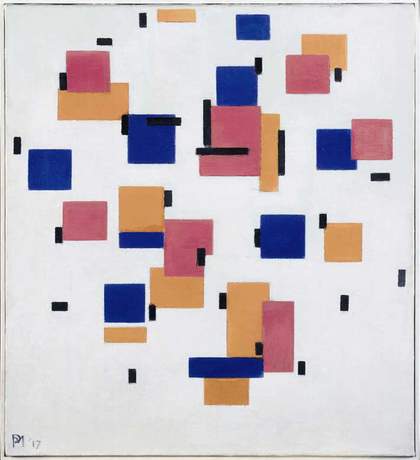

Just about all previous Mondrian exhibitions have been strictly chronological; there’s just something so compelling about seeing that steady path to abstraction when his paintings are lined up in date order (you can see the progression in the examples above, though his earlier work was even more figurative). But to see each painting simply as the inevitable next stage can make it seem as though Mondrian’s destination was worked out from the beginning, when in fact, his signature style was something he discovered, not something he planned.

Frequently overlooked are moments when Mondrian took a gamble, no more so than his decision to leave the Netherlands to make it as an artist in Paris. When he got on the train just before Christmas 1911, aged 39, he left behind a fiancée and established career.

It was a new Mondrian who stepped off that train and took a big gulp of smoky Paris air. He even dropped an ‘a’ from his name - Mondriaan - to mark the transformation.

He swapped his semi-comfortable life for a room in a shoddy block of artists’ studios, in a city with few personal contacts - and his sense of personal fulfillment increased enormously. He entered a fantastically productive period artistically, writing back to a friend soon after arriving: ‘You can be so wonderfully yourself in such a large, cosmopolitan city.’

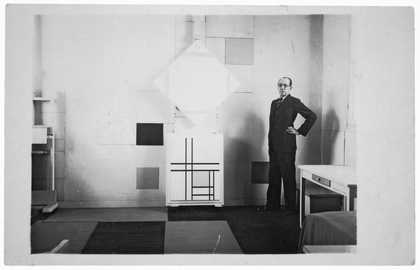

Mondrian in his Paris studio in 1933 with Lozenge Composition with Four Yellow Lines, 1933 and Composition with Double Lines and Yellow, 1933

Photo by Charles Karsten. © 2014 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR International USA

2. Make space

Mondrian’s achievements as an artist are intimately connected to the care he took to create the right atmosphere for his creative work.

Early in his career Mondrian took a year out from his hectic Amsterdam life and moved to a rural community in Brabant, in the south of theNetherlands. He learned to live with fewer material things and to value a plainer existence. When he came back, he began to de-clutter the studio he lived in and made it a more contemplative space.

Later in the 1920s, Mondrian’s Paris studio became a place of pilgrimage for artists, critics and art lovers. He steadily transformed it into a complete aesthetic environment, with coloured panels positioned on the walls according to similar principles as his paintings, and even across items of furniture as well. Guests were spellbound. The artist Ben Nicholson recalled an ‘astonishing feeling of quiet and repose’ after his first visit.

Reconstruction of 26 rue du Depart, Paris based on 1926 Photo by Paul Delbo

Photograph © 2014 STAM, Research and Production: Frans Postma Delft-NL. Photo: Fas Keuzenkamp © 2014 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR International

In 1938, concerned about the threat of war, and particularly having been branded a ‘degenerate’ artist by the Nazis, Mondrian felt compelled to leaveParis. His flight through London to New York led to an even greater sacrifice of possessions, but he reconciled himself to these losses.

In each of his final studios, before he attempted any painting, the first thing he did was get the space right.

3. Take your time

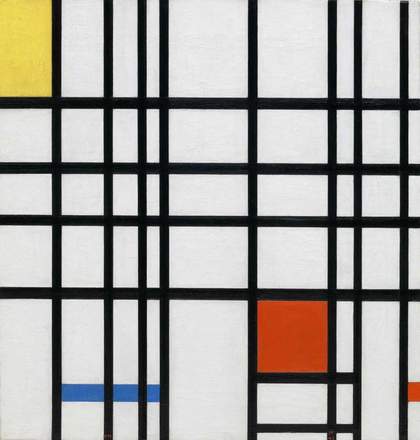

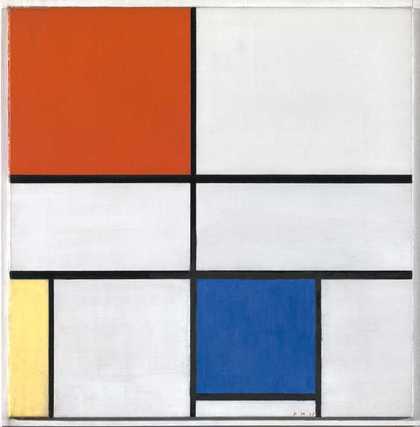

Some of Mondrian’s paintings have no more than two or three lines - look at Composition C (No. III) with Red, Yellow and Blue below, for example. You would think he could have knocked these lines out in a matter of minutes. But I go back and back to Mondrian’s paintings, and continually notice subtle effects of composition and colour I haven’t perceived before - and that’s because of the time he put into painting them. He didn’t use a ruler or measure them out according to any formula, but used the judgement he had accrued through decades of practice. You can tell from the beautifully textured surfaces of the paintings, on which brushstrokes are clearly visible, that these are handmade. Colours are built up in delicate layers of mixed paint, never squeezed straight from a tube.

Piet Mondrian

Composition C (No.III) with Red, Yellow and Blue

© 2007 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR International, Warrenton, VA

But there was also some mischief in Mondrian’s methods. When the New York art dealer, Sidney Janis, came to his studio to buy a painting in 1932, the artist told him that the one he was keen on was not quite finished. A small area of blue needed a further coat of paint - ‘but I didn’t get the picture for a whole year!’, Janis later recalled.

4. Strike the right balance

Often you’ll read that Mondrian’s painting is about balance. It’s true that he thought hard about the relationship between one area of a painting and another, but that only explains part of it. Mondrian avoided symmetry. He frequently placed larger areas of colour on one side of the canvas or the other, and the centres are often without much feature.

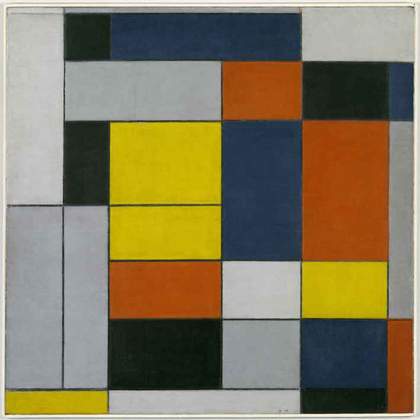

In 1920, Mondrian had a disagreement about this with a fellow artist over one of his paintings (we don’t know for sure which one, but it was likely very similar to No VI/Composition No II, below): ‘He said that [the painting] wasn’t balanced and that the yellow was disharmonious against the red, etc… I then told him that we were looking for a different harmony; he said there was only one.’

Yes, approaching things proportionally is a good thing to do but not at the expense of vitality and creativity. To repeat the same structure over and over is what Mondrian wanted to avoid. Instead he challenged his viewers to rethink their perceptions. Balance is easy, if it is just the case of one thing cancelling another out. Mondrian’s more open-minded approach keeps all the elements in play and motivated him to keep on painting and inventing new solutions.

Piet Mondrian, No. VI/Composition No. II 1920

© 2014 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR International USA

5. Be open to other ideas

Mondrian was an ardent dancer. He disdained the sentimental Tango but was keen on jazz and adored the Charleston - famous for its high energy. ‘All modern dances look feeble against such powerfully maintained concentration of speed,’ he commented.

When a journalist visited Mondrian’s studio in 1920, he was shown a painting that the artist said he wanted to title ‘Foxtrot’. ‘It has the same modern, rhythmic feeling, the regular steps to and fro,’ the journalist agreed.

In the mid-1920s Mondrian acquired a phonograph and began to buy records, and his studio became a place to dance as well as make art - and it is worth thinking more about the connection between them, both combining set phrases with flights of free expression.

While it often seems that Mondrian was intent on reducing art to its very essence, in fact he was very alert to the connections between it and other forms of cultural expression, and willing to learn from them.

6. Live each new day

Mondrian firmly believed that humanity would evolve to a higher state of being. He saw his paintings as beacons, lighting that path, after which art itself might disappear. Such forward looking gave Mondrian a sense of purpose and meant that he never opted simply to please his audience. He could have been financially successful had he remained a landscape painter and even in later years, he still had a ready market for paintings of flowers. At the same time, despite this lofty sense of what might be to come, Mondrian did not relinquish his enjoyment of painting or abandon making art; the paintings he produced in New York toward the end of his life are widely recognised for their verve and vitality. Mondrian described these qualities as ‘boogie woogie.’

There are important lessons to be learned from Mondrian’s career about not giving up and about the possibility of being creative at any age. However, the most telling instruction Mondrian gave to his viewers was that they should ‘live in the spirit of the approaching day.’ I take this to mean, don’t just live for the instant satisfaction of the present moment but also don’t defer all your enjoyment to the distant future. This can be applied to our own lives, of course, but it can also be applied to our appreciation of Mondrian. We can ponder the high-minded aspirations he had for his paintings in the future, but we must also enjoy them today as the beautiful objects they are.

Mondrian and his Studios is at Tate Liverpool from 6 June to 5 October