Philip Guston [archive recording]: It’s taken me years to come to the conclusion, or to the believe that the only thing one can really learn is the capacity to be able to change.

Michael Wellen: It’s late at night and Philip Guston can't sleep but he's making paintings of people who are. One of the things that really sets him apart as an artist is a sense of restlessness, his desire and willingness to change.

Anna Cooper: Guston was working with a lot of energy, he had something that he needed to get out and onto the canvas and I feel that energy when I'm looking at his paintings.

Michael Raymond: You get a sense of humour and there's so much imagery that is incredibly relatable to all of us, these are works which have something to say about the world.

Philip Guston [archive recording]: I was born in Montreal, Canada and at a very early age my family moved to Los Angeles, California. I worked at odd jobs at the time, I drove trucks, working in a cleaning plant doing all sorts of things and painted at night and weekends.

Michael Wellen: His father had been a trash collector in L.A. and took his own life when Guston was only about ten years old. Guston found solace in making art, he would tell stories of spending time drawing in the closet with a bare light bulb to find his own creative space. The light bulb becomes one of those reoccurring symbols throughout Guston's career.

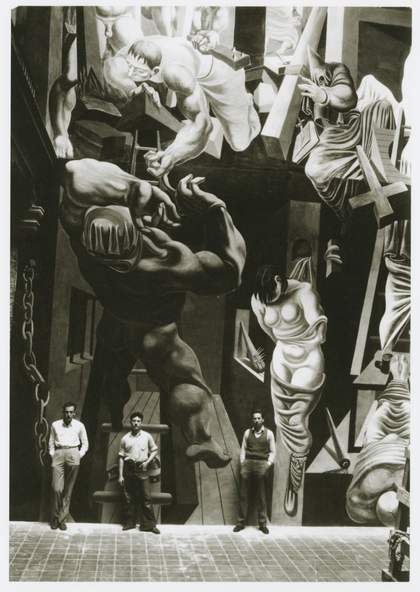

Guston is young, talented and he's starting to connect with other artists about how they could respond to the world in turmoil and how to use art in a political way. He's looking at the perpetuators of racist violence and particularly the Ku Klux Klan and these hooded figures. In the early 1930s Guston connected with a number of the great Mexican muralists, like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros and as a result of those connections he and his friends went to Morelia to make a mural called The Struggle against Terrorism. It’s just an incredible image to see how Guston is fusing together an interest in the Renaissance and in Italian painting from the 1500s and bringing that into the present day, working collectively with his friends to make a commentary on the times in which they're living.

It's also a time where he reinvents himself, he takes on the name Philip Guston, he was born Philip Goldstein. He was the youngest of Jewish immigrants who had fled anti-Semitic persecution in present day Ukraine. His wife Musa McKim, is also a mural painter and they move out to the Midwest together and they start a family.

Musa Mayer: He believed she had this sort of uncanny instinct for what was the most authentic part of his work, he would wake her up in the middle of the night sometimes to show her what he had done.

Michael Wellen: They have a daughter also named Musa who features in works like If this be not I. It's amazing to see the multiple sides of the artist in the space of one painting, we see conflict and we see tenderness.

In the early forties we see changes both in style and in the kinds of materials that he's using, he's consistently working with oil paint, painting allegorical scenes of children fighting. It's a time when the world is at war. You see him struggling through the course of the 1940s to figure out how to allegorise conflict

Philip Guston [archive recording]: I consciously thought of these children not as children, but as lost agonised beings. I felt that I had to figuration. I mean, I just had to go on a very lengthy struggle to do that.

Michael Wellen: And so his style begins to morph, the forms start to disappear and we are left with what looks almost like a kind of veiled series of hieroglyphs and sketches. He's beginning to let go of a kind of straightforward narrative or figurative scene.

Michael Raymond: In 1948 Guston is awarded this fellowship at the American Academy in Rome.

Musa Mayer: He just adored fresco painting and this was his first experience seeing it in the flesh.

Michael Raymond: That helped to unblock this crisis that he was facing, he then fully embraces abstraction.

Musa Mayer: It was his first real experiment with trusting himself and his intuitive process and finding a new way of working.

Michael Raymond: Throughout the rest of this decade in New York in the 1950s he's painting alongside the likes of Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline. He becomes one of the key figures within the New York abstract expressionist scene or the New York school. The forms start to become enlarged they start to fill the canvas they become blockier, denser more solid. After the 1962 Guggenheim retrospective Guston entered a new creative phase.

Philip Guston [archive recording]: I knew that I would have to someday and very soon get back to my earlier interests of the thirties and forties and really deal with forms.

Michael Raymond: At this point in his career he’s also watching the tumultuous events play out in America and in the world stage. You get this real sense of him grappling with wanting to make political art that made a statement about the horrors and injustices that he saw in the world around him.

Philip Guston [archive recording]: Guston: The war, the political conventions state of the world, everything I don't think it's limited just to America either I mean, the violence in the world ever since I’ve been alive which everybody, everyone experiences that

Michael Raymond: He returns to this imagery that had haunted him since he was a boy the Ku Klux Klan and he utilises the hood as really a symbol of evil that's everywhere in society.

Michael Wellen: In 1970 Guston shows what he's been working on for the last couple of years, large-scale paintings of hooded figures. it’s like a bomb has dropped.

Philip Guston [archive recording]: Some painters that I had known for years wouldn't even talk to me, De Kooning put it a better way he said: “what do they think? we're all on the same we're all on a baseball team?”.

Michael Wellen: We’re looking at hooded figures, not at the moments of violent acts but in the periods in between when they're plotting, resting and smoking a cigarette, waiting to create some kind of havoc. They are really uncomfortable to look at and part of what makes it so uncomfortable is also that they're visually really interesting to look. So they lure us in with their strange kinds of cartoonish appearance and bring us into a very dark place even if they're brightly coloured. What makes these so disturbing is the everyday nature of this kind of evil that Guston is looking at and the way that it runs through all of society and through all of us. Guston talked about his own self-awareness, his own kind of culpability, imagining himself behind the hood and trying to understand what it means to be evil.

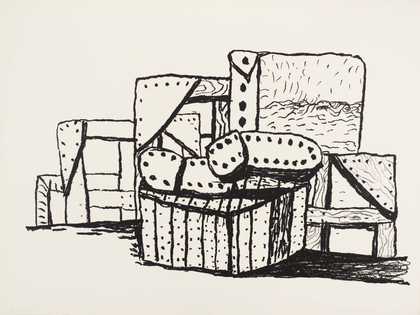

Michael Raymond: After the Marlborough show opened Guston was incredibly wounded by the critical reception that his new works received and so both him and his wife Musa McKim returned to Italy, a place of solace and comfort for Guston. Guston returned to Woodstock in upstate New York and there away from the attention of the art world he embarked upon creating large canvases full of this strange and uncanny and almost dreamlike imagery, in which junk or what Guston called crapola would be spewing out of a mouth or piling up in large mounds in the centre of a painting.

Michael Wellen: One of the interesting parts of Guston's career is his collaborations with other artists especially with poets and with musicians, the ways they would inspire each other.

Musa Mayer: The poem pictures are really a collaboration between my parents, in other words my mother had written various poems and my father illustrated verses of those poems that he felt particularly drawn to. So you have this wonderful collaboration of his imagery and her words.

Michael Wellen: He brings back these themes and motifs throughout his career, they take on new meanings each time he re-employs them.

Musa Mayer: My mother's head appears repeatedly but then it takes different forms. Perhaps the most devastating thing was that my mother suffered a pretty severe stroke. It really terrified my father.

Michael Wellen: And yet the works that he's making at that time are so filled with energy and emotion.

Anna Cooper: He's working with wet oil paint layering different colours together within one brush stroke. I can see black green, white and they're all peeking through in different ways. It's exciting because there's so much more to see than you would initially think.

Michael Wellen: Guston talks about wanting to come into his studio in the morning and be baffled by what he had painted the night before and he's managed not only to surprise himself, but us as viewers.

Michael Raymond: He is someone who is completely at the top of his game as an abstract painter and just buries that and goes in a completely different direction, it was such a daring move and I think he really opened up figuration to a new generation of artists.

Michael Wellen: He's struggling with all of the dimensions of life, its happiness and its sadness and trying to capture it and create paintings that inspire us to think about what we do in the short lives we have.

Philip Guston [archive recording]: This serious play which we call art, can’t be static. I mean you have to keep learning how to play. As modern artists, that’s our fate is constant change.