Klee’s one of the towering figures of the Twentieth Century. It’s easy to see pieces of his work, to think about the line drawing or to think about the works that are simply abstract. But what we’ve tried to do, by arranging things chronologically, is to show that he is incredibly various at any one moment.

Klee made this work while he was a soldier in the German army. He was a German national even though he’d been born in Switzerland. Although, Klee seems to be rather withdrawn from the terror of the First World War, I think this painting does reflect some of that chaotic experience. So, you see the zig-zaggy lines that pour in from all sides and they surround sequences of fragmented heads, and at the centre right here, pretty much certainly, a self-portrait of Klee. It’s a self-portrait but it’s also capturing a critical moment in the history of Germany at that time, but through an abstract language.

Just after the First World War he emerges in Germany as the key artist of that generation. Well, this is sort of a redemptive moment for art in Germany. They could move beyond the destruction of the war and look at modernism in a new way.

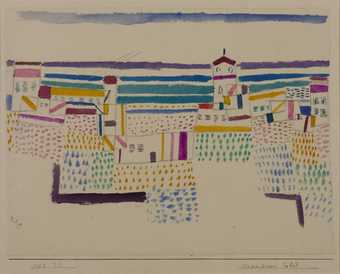

One of the things we wanted to capture in the exhibition is how his work is extraordinarily various, and that’s shown in these two paintings. This painting seems to be something like a still life; they look like sort of checkerboards, we know those come from seed pods and from the way in which leaves grow up stems, almost a set of objects laid out on the table. We know that this is 1923 No. 79. No. 80 is this work behind me. You can really see the contrast in the ways he’s working. It appears to be a, sort of, random arrangement of blocks of colours but when you really start to look closely at it you can see that it fits into big plains. And, the critical area is this small blue rectangle because if you extend the side of each of the sides of the blue it triggers the whole structure of the composition.

The importance of 1923 is that he’s developing modes of abstraction in totally revolutionary ways, but in rather extraordinary circumstances; a moment of total meltdown in the German economy for instance. And, Klee and his colleagues are working in this rather idealistic way, trying to form a new society that extends beyond the immediate circumstances they find themselves in. But that comes at a moment just prior to the rise of Nazism in Germany, and in ’33, basically, everything goes wrong.

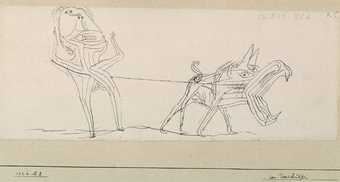

Here we are right at the end of Klee’s career. The cultural world in which he’d been working in Germany had closed down, the people he knew were dispersed around the world. After returning to Switzerland he fell very ill and his illness was restricting his movement, and yet this is probably the biggest work he ever made in his life. So, there’s an extraordinary sort of, defiance in the way that Klee’s setting about making this work. It’s the most uplifting of works, it seems to me. He seems to be opening up avenues rather than closing them down.

It’s these sorts of works that became the stimulus for all sorts of other artists; people like Mark Rothko or Victor Pasmore, in London. Klee had this extraordinary influence through, literally, the life and death struggle of his last couple of years of painting.