Nam June Paik was a truly global artist. Born in South Korea, he lived and worked in Japan, Germany and the United States. He was one of the first Asian artists who found success in the West.

In his art, Paik saw technology as a way to open up the world and connect with people in different countries—beyond national borders and cultural differences.

He experimented with TV, broadcasting, synthesisers and robots, and was one of the first artists to use video as art.

Through his work, Paik predicted the following things about the future of technology.

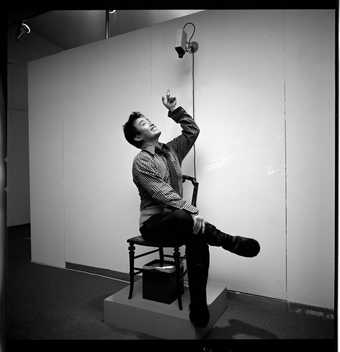

Nam June Paik sitting on TV Chair. Image courtesy ZADIK © Friederich Rosenstiel.

The future will be connected

In a 1974 essay, Paik proposed the building of new ‘Electronic Super Highways’. These networks could connect faraway cities through satellites, cables and fibre optics. Physical distance would then no longer be a barrier, he reasoned.

Nam June Paik, Internet Dream 1994. Image courtesy ZKM Centre for Art and Media, Karlsruhe © Estate of Nam June Paik.

Conferences between people in different locations via color video telephones will become commercially feasible. Video-teleconferences that consume no energy (though there is the initial cost of copper) will drastically reduce air travel, and along with it the chaotic shuttling of airport buses through city streets – forever!

Nam June Paik, Media Planning for the Postindustrial Society – The 21st Century is now only 26 years away 1974

‘The gains will be tremendous, environmentally and energy-wise,’ he wrote. ‘It will become our springboard for new and surprising human endeavors.’

Paik was not the first to predict a worldwide digital network, but he was the first to understand its repercussions on our day-to-day communications—foreshadowing not just the Internet, but also apps like Skype and FaceTime.

Twenty years later, Vice-President Al Gore popularised the term ‘information superhighway’, claiming it as his own. Paik joked in response, ‘The White House stole my idea’.

The future will be global

Through his travels, Paik had the chance to meet inspiring and daring artists, musicians and engineers — including composer John Cage, cellist Charlotte Moorman and artist Joseph Beuys. Some became lifelong friends and collaborators.

But Paik wanted his art to travel even further than he did. With the help of mass media, ‘I want to place culture out of nationalism and communication out of vanity and SNOBISM [snobbery],’ he stated.

Between 1973-88, Paik created four live TV broadcasts that predicted, one day, we could access world events at the touch of a button. The first broadcast, Global Groove, opened with the announcement:

This is a glimpse of a new world when you will be able to switch on every TV channel in the world and TV guides will be as thick as the Manhattan telephone book.

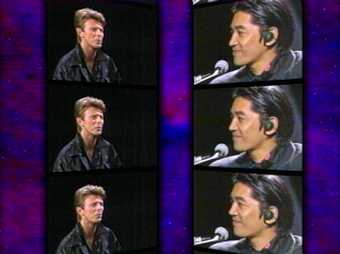

British and Japanese musicians David Bowie and Ryuichi Sakamoto meet on-screen as part of Nam June Paik's ambitious 1984 broadcast, Wrap Around the World. Image courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York © Estate of Nam June Paik.

Ten years later, Paik’s satellite broadcast Good morning, Mr Orwell streamed events live from New York and Paris to audiences in the USA, Europe and Korea.

Paik’s final satellite broadcast Wrap around the World was even more ambitious. The video reached over 50 million viewers in 10 countries, from the USA to Asia and the Soviet Union. At a time when travelling in the Eastern Bloc was almost impossible, Paik’s art breached the Iron Curtain, sharing images of David Bowie chatting in Japanese, a car race in Ireland, the Viennese Art Orchestra, and a game of elephant soccer in Thailand.

The future needs to be sustainable

Paik believed that technology needed to be in harmony with nature. In his artwork TV Garden, he placed dozens of TV sets among a jungle of tropical plants. Viewers immersed themselves in this natural world while they watched the screens.

Paik noted that people would see plants and TVs together as a ‘paradox’. But, for him, this was all the more important to show that the two are connected.

Many people had thought that television is against ecology. But in this case, television is part of ecology.

Nam June Paik TV Garden 1974-7 (2002) Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen (Düsseldorf, Germany) © Estate of Nam June Paik Photo: Tate (Roger Sinek)

Many of Paik’s early artworks were inspired by Zen Buddhist concepts. He may have personally believed the Buddhist idea that everything in the world is connected—even things as diverse as electronics and plants.

Paik also believed that we should find fulfilment in art and culture, rather than consuming natural resources.

In 1980, when he was asked, ‘If you were elected president, how would you solve the world’s problems?’, he replied that he would ‘make oil obsolete’ and use information as an energy source.

Globally, we are using too much fossil fuel but not getting enough spirituality, he advised. ‘We need worldwide dieting. Lose weight.’

Dancers and yogis achieve ecstasy with 200 calories. However, racing drivers, if they want to achieve ecstasy, have to burn 200,000 calories… when we shift our economic priorities of consuming to more spiritual sphere then we can solve all economic problems with much less energy.

Nam June Paik interview with Lynn Hershman Leeson, first published by Artweek, April 1980 Electronic Art.

The future will be televised

Paik began experimenting with TV in his art in the early 1960s. His first solo exhibition in 1963 showcased 13 manipulated TV sets. Later, he would build robots out of TVs and direct his own broadcasts. He saw TV as a way to reach people through a shared experience, no matter where they were in the world.

In Paik’s future, TV sets would eventually become a ‘mixed media telephone system for 1001 new applications’. You could use it to watch shows, make video calls, go shopping and much more.

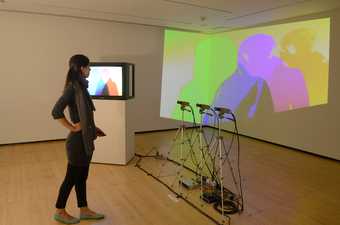

Paik was also optimistic that, in the future, anyone could easily make and share a video. Affordable cameras have already given people the chance express their creativity, he realised:

The invention of camera changed the scene and made everybody into an active visual artist. The size of camera industry and art business illustrated the massive desire to create an artwork, instead of watching a masterpiece on the wall. Will this process repeat itself in the TV world?

Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik, Three Camera Participation/Participation TV 1969, 2001. Image courtesy Asia Society, New York © Estate of Nam June Paik.

Video cameras did become more accessible and video as art grew, as Paik hoped. After all, his pioneering work paved the way for it.