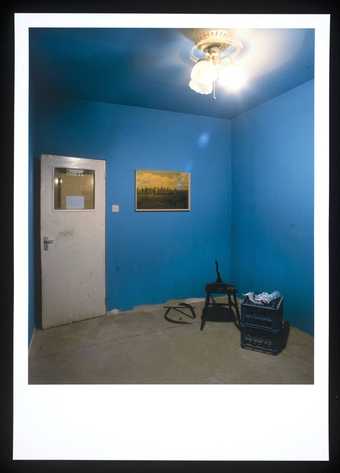

The exhibition’s title is The Coral Reef. It was built in 1999 but opened in January of 2000 in Matt’s Gallery in the East End, and it’s been rebuilt for the first time now, almost exactly ten years later. The Coral Reef kind of referred to an idea of an ocean surface, like referring to the idea of an ideology, like a prevalent ideology, an economic one of capitalism, under which a sort of coral reef, a complex of fragile structure, different sort of belief systems, existed. So in a sense, each different room was indicative of a different sort of belief system. So as you walk through, the first room you come to is the faked kind of reception of an art gallery, and the second one you come to is an Islamic minicab office, where you come to the back office, and you come back to later on within the works, which is a replica of itself, and then on to a room of Americana, a room of heroin, a room with dope, a room with bike mechanics, like worshipping the automobile, the car, the motorbike, and one room that is just a void, or empty like the unseen, the unknown, the other, sort of like the room of horror, ultimately.

I was looking for body structures which perhaps interested me, or that I saw that were prevalent around me, but somehow occupied a position of void in the face, or almost futility in the face of structure we kind of live within, call it what you will. Especially at that point, because this is back in 1999, and opening in January 2000 – this is over a year before 11th September and July 7th, so it’s kind of like relationships between the East and Islam. It seemed like a very disempowered belief structure, in a position which somehow couldn’t be heard.

I think this work’s kind of re-dating of that moment somehow makes it more interesting and more kind of… like there’s a distance there, which helps it ultimately, because when there are real lives involved in such things that art might refer to, it becomes far more complicated to actually make sense of something within a short term timescale – even though you know that it’s ultimately a complete fiction that you’re walking into, because you know this is the Tate Gallery. You know, you might allow yourself to go with that. I think I always used to make the analogy of reading a book. You know, you sit down in your armchair and you could be sailing the seas, fighting the First World War, sort of… you know, sleeping with a concubine in God knows where – you could be doing anything, ultimately, if you had agreed to go with that fiction within the first few pages. And the idea is that you are invited to become lost in this lost world of lost people.

The only [inaudible 00:03:43] making a far more sort of didactic work, more political work, which demanded a far more linear or teleological reading, in a more art sort of way, and at the same time I started developing a sort of more narrative-driven work, which to begin with, they were like, objects, props and scripts from non-existent films. So in a sense, this was the first word, I think, that really sort of managed to equate a literary structure to a spatial structure. You know, I think for me it only really worked if you think of it within its context, of when it was made. It becomes very archival, it becomes, like, historical. It’s like a mise-en-scène from another time, and that all becomes stronger in time as it’s rebuilt, because even a really banale thing like a piece of [inaudible 00:04:33] becomes like a strange relic from another age already. And the meanings will ultimately shift – it won’t have that immediacy and that sense of being about that moment. It will be about another moment that’s passed.