We’re in what I… again what I would call my clean studio, which is, sort of, a combination of archive library storage, working space, editing space and thinking space. I’m, you know, a book fanatic and I like this really messy way of working, that when I’m working on my stuff, I’m surrounded by the works of people I’m interested in. You know, I could be staring at something on the bulletin board there, some print I hung up while I’m making breakfast. I like that level of evolvement, you know, I’ve been trying desperately to figure out what I don’t need anymore, so I could pack it away and get more space but I sort of feel like I need it all. I live with the work so I need access to everything; I need to see it at 2 in the morning.

This is sort of what I call my worry board, I put up stuff here that I’m kind of thinking about. You know, if I’m interested in that notion, I’ll make some prints of the negatives I shot and just throw them up there and live with them for a while. That’s what we’re looking at here.

All my work sort of develops out of, sort of, just being out there and photographing and looking around. So when I did the work on the abandoned railroads, the American Canadian West, which was published as Westward the Course of Empire. I worked on that for 14 years and over a couple of years it became very clear why I wanted to do it, what I wanted it to look like and ultimately even what the structure of the book version of that might be. But, the first pictures in that series I made because I was out somewhere in Utah, working on some other idea and I came upon this abandoned railroad line. I made some pictures, they lay around, the wheels turned, gradually it became this much more, sort of, organised and intellectualised process.

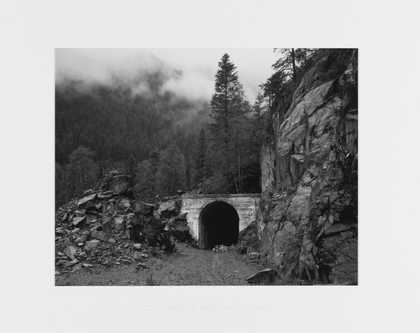

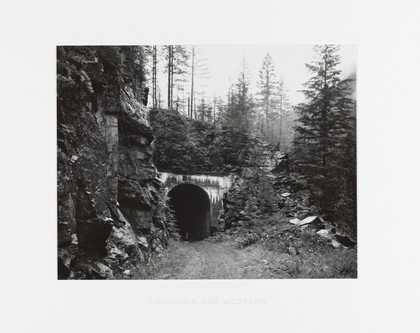

That book has 72 pictures in it, but I made 500 or more pictures that I actually liked, it’s not just total negatives but actual pictures that had some interest for me. Because those pictures were always coupled with the original name on the railroads, so you have this picture of, sort of, almost nothing, dirt, but underneath it, it would say, on the mount, it said The Denver and Rio Grande Western or something, so it took the landscape and located it in a historical drama. One of things that I was really keen on with landscape photography, was that I was photographing history. Landscape is both… it’s active, it’s not like just the stage, but it is the stage of human endeavour, while simultaneously being, kind of, an agent in its own right and I like that, that conflict as well.

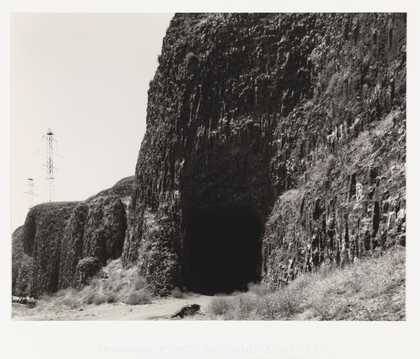

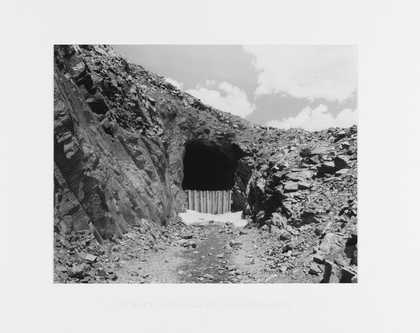

I think the railroad cut, which was, sort of, the central visual motif for this project we’re talking about, on the railroads, is kind of deep cut through the rock, that has to do with a very dynamic relationship with technology and terrain. The railroad could only… I forget the number, but it could only maintain a certain grade of elevation, so if the mountain was too high, they cut away the mountain. There’s a certain ambiguity in whether we’re looking at something that was cut by a human hand or something that was formed naturally and I’m really interested in those dynamics. One of the great things about photographs is that they document, regardless.

No matter the intention of the photographer, over time, photographs accrue documentary value and that’s kind of interesting too. So maybe it’s not a really successful picture, but maybe 50 years from now, it has some other kind of use value that’s, sort of, interesting.