Artist’s studio on Washington street, Warsaw. Abakan Round 1967–8 and Abakan Yellow 1967–8. Photo © Estate of Marek Holzman. (c. 1968)

1. Confronting History 1930–60

The Second World War shaped Abakanowicz’s early life. Once the war ended, she joined in rebuilding a cultural scene of inquiry and innovation in Warsaw.

I am a historic being like all of us ... I carry within myself an ample portion of humanity prior to history. On this ahistoric part of my being - of every being - is impressed, like an effigy, a memory of the most ancient sensations and feelings. In materializing them, I speak through them about my reality. It is a union of the most ancient and the fresh experience.

Magdalena Abakanowicz

1930

Born Marta Magdalena Abakanowicz in Falenty near Warsaw, 20 June 1930. As the second daughter her birth is a disappointment in establishing a lineage that would unite her father’s Russian and Tatar heritage and her mother’s Polish nobility.

1939

Nazi Germany invades Poland on 1 September 1939 and Soviet troops follow on 17 September, marking the beginning of the Second World War. The family resettle in their estate deep in the forest near the village of Krępa, 140 kilometres from Warsaw.

1943

German soldiers break into the family home and wound Abakanowicz’s mother, severing her arm at the shoulder.

1944

The family flees to Warsaw, only to be separated during the turmoil of the Warsaw Uprising by the Polish underground resistance. German reprisals lead to the complete destruction of Warsaw.

1945

With the end of the War. Abakanowicz enters middle school, having previously been tutored at home.

1948–49

As her family seeks opportunities further north in Tczew near Gdańsk, she attends secondary school for plastic arts in Gdynia.

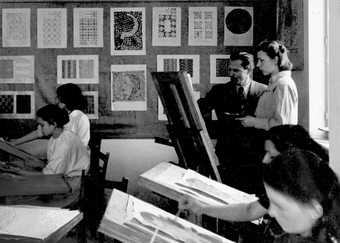

Artist (standing) at secondary school for plastic arts, Gdynia, Poland. Photo © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego. (1948–9)

Abakanowicz and her husband Jan Kosmowski at their wedding reception. Photo © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego. (1956)

1949–50

She studies weaving at the fine arts school in Sopot, but when this programme is suspended, she transfers to the Academy of Plastic Arts in Warsaw. She begins to use her middle name, Magdalena, to disguise her landowner roots for fear of being exposed as a class enemy in Communist Poland.

1954

Graduates from the Painting Department at Academy of Plastic Arts in Warsaw with a specialization in Weaving. In Warsaw, she meets Jan Kosmowski (1930–2018), a civil engineer studying at the Warsaw University of Technology. They marry in 1956.

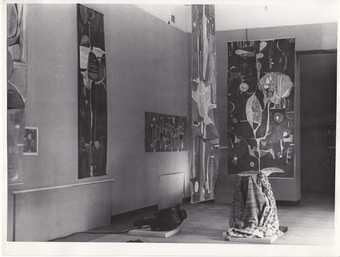

Wystawa prac Magdaleny Abakanowicz-Kosmowskiej (Exhibition of works by Magdalena Abakanowicz-Kosmowska), at Galeria Kordegarda, Warsaw. Composition 1960 is shown freely hanging to the right. Photo © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego. (1960)

1954–60

While seeking to pursue her own art, Abakanowicz finds employment in industry and participates in state-organised design exhibitions.

III Ogólnopolska Wystawa Architektury Wnętrz (3rd State Exhibition of Interior Design), showing Butterfly 1956–7 hanging from the ceiling of the National Theatre in Warsaw. Photo Archives of Museum of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. (1957)

1960

Her first solo exhibition of oil and gouache paintings is held at the Ministry of Art and Culture’s Galeria Kordegarda in Warsaw, but it is closed by authorities before it opens to the general public.

The first show – what an excitement. I came one hour before the opening to check all the details. I could not enter; the door was locked … The next day we learned that the authorities found the show to be ‘formalistic,’ that means not engaged with building socialism, thus a tendency disapproved in art. The show was closed before it ever opened. We realized that the ‘thaw’ that had come after Stalin’s death was over. The old rules returned.

Magdalena Abakanowicz

2. Finding Her Place 1962–70

Abakanowicz begins to find her own artistic language. As she resists pre-defined categories of tapestry, textile, craft, decorative art or fine art, a new genre is named for her: ‘Abakans’. She becomes recognised for her efforts and exhibits throughout Poland and internationally.

The Abakans were a kind of bridge between me and the outside world. I could surround myself with them; I could create an atmosphere in which I somehow felt safe because they were my world; they were something between figurative and natural, like animals, like figures, while abstract, like geometric forms, but never to be definitively described.

Magdalena Abakanowicz

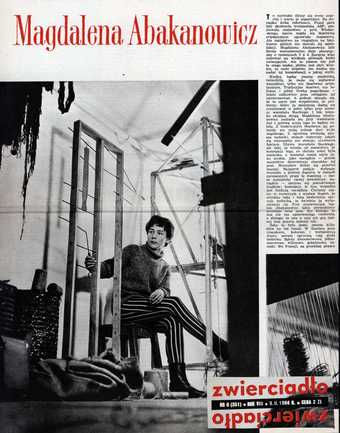

Zwierciadło magazine (351, no. 6, February 9, 1964), article by Elżbieta Żmudzka in which ‘Abakans’ is used for the first time. (1964)

1962

Abakanowicz is invited to the 1st International Tapestry Biennial in Lausanne, Switzerland, one of three Polish weavers. This will be her first international exhibition.

1964

Polish art critic Elżbieta Żmudzka, writing in the journal Zwierciadło: ‘How to name the woven paintings of Magdalena Abakanowicz? Maybe – Abakans?’

1965

Represents Poland in the 8th São Paulo Biennial and is awarded the Gold Medal in Applied Arts. She uses the prize money to move to a cooperative housing block in Warsaw with artist studios on the top floor. She lives and works here with her husband until 1989, when they move into a home and studio of their own.

I never felt that my studio was small, except when I had to move big pieces out of it, I had to go through the window on the 10th floor. I had an enormous view through my windows and lived more in this view than in the room. Mentally, I was still in Polish forests in the Polish country which I love in an extremely strong way because I know every end, I know every leaf, I know every piece of grass … This is my world and I never got out of it since my childhood.

Magdalena Abakanowicz

In 1965 she is appointed a professor at the State Higher School of Plastic Arts in Poznań and teaches there until 1990. In 2020 the school is renamed the Magdalena Abakanowicz University of the Arts.

City view from the artist’s studio on Washington Street, Warsaw. Photo © Artur Starewicz/East News. (1981)

1967

She produces her first fully three-dimensional sculptural forms.

1969–70

Creates the film Abakany 1970 on the sand dunes of Słowiński National Park in Łeba along the Baltic coast of Poland.

3. Creating Experiences 1970–83

Abakanowicz begins to envision her works not as discrete objects, but rather as environments in space. Rope becomes a repeated motif, allowing her to connect works into installations.

With my exhibitions around the world, I wanted to make people aware that my captive country still has a high level of old culture contributing to the world heritage, and is at the same time is able to speak about the recent reality with the very personal strong voice of modern art. I travelled probably more than any other artist. So important was the dialogue with the whole world.

Magdalena Abakanowicz

Artist in front of Bois le Duc, Provinciehuis van Noord-Brabant, ’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands. © Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitable Foundation. Photographer: Jan Nordahl. (1972)

1970

Her first installation project – in essence a massive temporary work built of Abakans and rope – takes place at the Södertälje Konsthall, Sweden.

She receives her first major public commission for the theatre at the Provinciehuis van Noord-Brabant in ’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands. She titles it Bois le Duc (the duke’s woods) in honor of the area, known informally as ‘Den Bosch’ (the Forest). The title also points to her childhood exploring Polish forests. In the 1970s she has 21 solo shows and participates in over 75 group exhibitions in Poland and worldwide.

1972

Rope threads through her temporary installation projects, most notably at Edinburgh International Festival in 1972. She uses a long stretch of painted red cable through the city.

1973

By 1973 she begins to use reclaimed burlap sacks to create human forms, beginning with Heads, Seated Figures, and Backs.

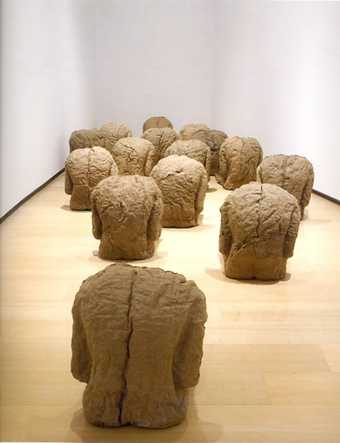

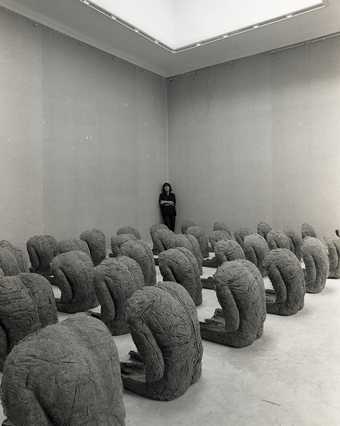

Exhibition view of Abakanowicz at Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, showing Heads 1973–5 and Seated Figures 1974–9. Photo © Artur Starewicz/East News. (1982)

1974

Receives an honorary doctorate from the Royal College of Art, London. This is the first of 6 honorary doctorates awarded to her, along with national honours from Poland, Austria, France, Germany and Italy.

1976

Installs exhibitions in Sydney and Melbourne, Australia. Between museum venues she travels to Papua New Guinea.

1978–80

Writes a prose poem narrating her experiences from childhood to the end of the Second World War. It becomes the starting point for her autobiography Fate and Art published in 2008.

1980

Represents Poland at the Venice Biennale. Her space is structured as a total environment and includes for the first time Embryology and her iconic Backs.

1981–83

Martial law is declared in Poland on 13 December 1981 in an attempt to suppress political opposition. It would not be lifted until 1983.

Exhibition view of Polish Pavilion, Venice Biennial 1980, showing artist with Backs 1976–9. Photo © Artur Starewicz/East News. (1980)

4. Human/Nature 1985–98

Beginning in the 1980s Abakanowicz’s work reflects her thoughts on our capacity for violence to each other and to the natural world.

1985

Abakanowicz begins the Crowd series 1985–2014: anonymous, headless, yet individual figures.

1987

She begins the series War Games 1987–95. Encountering felled trees in the Masurian Lake District, Poland, she creates a total of 21 huge forms that suggest both weapons and bodies.

The artist working on War Games 1987–95 in the Masurian Lake district, Poland. Photo © Artur Starewicz/East News. (1987)

1989

The fall of communism begins peacefully in Poland on 4 June 1989.

1990

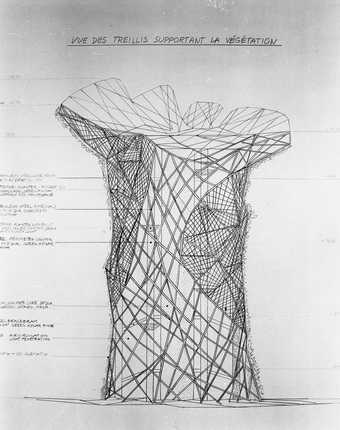

A competition is launched to redesign La Défense, a business district in Paris. Abakanowicz is one of four finalists. Her vision – Arboreal Architecture – is a vertical, habitable garden of residential and commercial towers.

Magdalena Abakanowicz with Andrzej Pinno and Halina Starewicz. Technical drawing for Arboreal Architecture. Photo © Artur Starewicz/East News. (1991)

Arboreals symbolise our concern with nature which, neglected and abused by man, now turns against him with vengeance. They remind us that a tree is our friend: it gives shade and oxygen, bears fruit, shelters birds and animals, and makes climate hospitable to all.

Magdalena Abakanowicz

1991

The Soviet Union is dissolved on 25 December 1991.

1992

She begins the series Hand-like Trees 1992–2004, as a sculptural response to her unrealised Arboreal Architecture. A public petition requests Abakanowicz be commissioned to produce a permanent work in Hiroshima, Japan, as a memorial to the victims of nuclear destruction. She proposes a hand-like tower, as if to catch the bomb. After finding it might be perceived as too aggressive, she creates a monument of 40 silent seated bronze backs: Space of Becalmed Beings 1993.

1998

She creates Space of Unknown Growth, a massive land art project near Vilnius, Lithuania, consisting of 22 concrete ovoid forms.

On the geological clock indicating four billion years of our globe, human activity producing culture occupies only the last few seconds. Within this span of time the human species has managed to threaten not only the biological and environmental balance, but also itself.

Magdalena Abakanowicz

Installation view, Magdalena Abakanowicz: Bronze Sculpture, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, UK, showing Hand-like Trees 1994. Photographer: Clare Lilley. (1995)

Space of Unknown Growth, Europos Parkas, Vilnius, Lithuania. Photo © Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitable Foundation. Photographer: Norbert Piwowarczyk. (1998)

5. Sites of Contemplation 1985–2019

In her late career Abakanowicz undertakes major commissioned public sculptures around the world, responding to the unique landscape and history of each site.

Katarsis, 33 figures in bronze. Giuliano Gori Collection, Fattoria di Celle, Santomato di Pistoia, Italy. Photo © Artur Starewicz/East News. (1985)

1985

Begins her first major permanent outdoor installation for the Spazi d’Arte sculpture park, Italy. Katarsis is a group of 33 standing figures and is her first work in bronze.

1988

Commissioned to make a permanent public work for the Seoul 1988 Olympic Games. Space of Dragon consists of ten massive bronze animal heads.

1987

Creates Negev at the Billy Rose Sculpture Garden, Jerusalem. Abakanowicz is impressed by the local limestone filled with fossils. Stonemasons carve seven ten-ton wheels that sit along a precipice. Negev is a response to the barren desert, the silence of its rocks, and the prehistoric shores of the Mediterranean. At the same time, its round forms resemble wheels or millstones.

Negev, 7 wheels in limestone. Collection Israel Museum, Billy Rose Art Garden, Jerusalem. Photo © Artur Starewicz/East News. (1987)

Sarcophagi in Glass Houses, made from wood, glass, and iron. Collection Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, New York. Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitable Foundation. Photo courtesy of Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, New York. (1989)

1989

Visits a French iron and steel mill where she is intrigued by the belly of giant wooden forms used for casting engines. She transforms four, encasing each like a body in a glass greenhouse-like structure: Sarcophagi in Glass Houses. In 1994 this work was permanently sited at Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, New York.

In ancient times a sarcophagus was a coffin of limestone thought to have the property to quickly dissolve its contents—its name originating in the Greek word ‘sarkophagos’, meaning flesh eater. But then I heard on the news that a sarcophagus will be built for the atomic reactor in Chernobyl in Ukraine. It means that in our times, the sarcophagus has to cover dangerous technology.

Magdalena Abakanowicz

2002

Unrecognized 2002 is inaugurated in Park Cytadela, Poznań, Poland, a public project urged on by former students of the artist. It consists of 112 headless, two-meter tall iron figures, each striding off in their own individual direction.

2004

On 1 May 2004, Poland joins the European Union.

2006

Abakanowicz completes Agora for Grant Park, Chicago. Begun in 2003, this is her largest – and last – permanent public project: 106 headless figures, each nine-feet tall and cast in iron.

We live in times which are extraordinary because of their various forms of aggression. Today new danger exists around us as if everyone were against everyone. Agora should become a symbol, a metaphor about this particular historical moment in which we need each other, in which we want to rely on each other more than ever.

Magdalena Abakanowicz

2017

Abakanowicz dies in Warsaw, Poland on 20 April 2017. She is buried in the Powązki Cemetery, the oldest in the city.

2019

The Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitable Foundation, established by the artist and her husband Jan Kosmowski twenty years earlier, begins to award grants. It supports scholarly work on the artist and legacy projects which sustain her belief in the dynamic force of art in society.

Agora, 106 iron cast figures installed at Grant Park, Chicago. Photographer: Kenneth E. Tanaka. (2006)

All Artworks © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, except for Abakan Round, which is © National Museum in Wrocław