Lowry is the sort of artist everyone has a story about – but surely no one has more than Mick Coleman and Kevin Parrott, who met me at Tate Britain to explain that the artist basically painted their lives. Oh, and they returned the favour with a jingly number one you might remember from 1978.

They are, of course, the infamous Brian and Michael (said Brian being a previous band member, Brian Burke), then two young folkies responsible for getting cats and dogs and sparking clogs stuck in your head for 19 weeks, when Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs made Top of the Pops.

‘It was a simple song about someone we loved,’ Mick explains, suited and smiling at the occasion of their hero’s first major show in London. ‘I’ve always loved Lowry and his paintings. It was an affection more than knowing anything about art, really.’

But not everyone was pleased about that, Kevin says. ‘We had a lot of criticism in the early days. There were people who treated the song as by two guys who really didn’t know anything about Lowry and his painting. Who were we to write about art?’

Well, he says, they were the subject of Lowry’s paintings, of course.

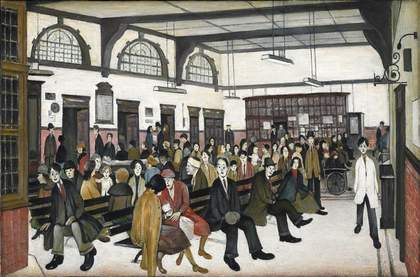

Lowry's 1952 depiction of Ancoats Hospital waiting room - a place Mick Coleman knows well

Mick takes me to see Lowry’s Ancoats Hospital Outpatient’s Hall, and pointed out the exact spot where, aged eight, he sat bloodied in the waiting room after being mugged, and sadly lost his eye. ‘And the hospital looked exactly the same,’ he says. ‘A lot of the paintings I can see here were exactly where I played when I was a kid.’

Growing up in where Lowry used to do his rent collecting, Mick, his mother and his siblings lived in Britain’s last workhouse. ‘We were there for seven years. So when you see the poorer areas that Lowry painted, it takes me back to those days that were even quite painful,’ he says. ‘There were cripples, people with no arms and no legs, and you think, what kind of picture is that of Manchester? Well, it was a true picture of the Manchester I lived in.’

Parrott first encountered Lowry’s paintings when he was eleven, taken to Manchester Art Gallery on a school trip. When he got home, he begged his mum to buy a print of Lowry’s The Procession – but ‘you couldn’t get them in those days, you had to have that green Chinese lady.’

Years later, when they were on Top of the Pops, a publisher of Lowry’s prints invited them to their West End offices to thank them. ‘They said that before the record came out, they hardly sold a Lowry print, and afterwards they couldn’t keep up with the demand,’ Parrott recalls.

The pair never met ‘Mr. Lowry’, although they came very close, apparently. Parrott had planned to meet him at a mutual friend’s house, in the hope that Lowry might paint something for the cover of his new album - but when that friend went to collect Lowry, he found him collapsed in his hallway, and he died in hospital the next week.

Coleman penned Matchstalk Men the following year, on the back of a cigarette packet sitting on the end of his bed. ‘It came from beginning to end in about half an hour.’

Parrott, in another band at the time, dropped everything to produce it with his own cash, ‘taking it all over the place’ before Pye Records picked it up. His concept was ‘a Lowry picture in sound’ – based on The Procession, which was by that time hanging over his mother’s fireplace.

They used ‘matchstalk’ rather than stick, both because it’s the local pronunciation and because it sounds softer in the song, Parrott explained. Some curators aren’t fond of the term, feeling that it pigeon-holes Lowry, but for Coleman and Parrott it’s a term of endearment – and one that they say others felt too.

‘It got the word out about Lowry. They call us ‘one-hit wonders’, but we’re here today, aren’t we? And now, when we play the song we get squeezed by large ladies and men with tattoos, telling us how many memories the song has for them.

‘It’s funny, the song has come of age I suppose - and so has Lowry. Here he is in the Tate among some of the greats, and that’s a great day for us.’

Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life is at Tate Britain until October 20 2013