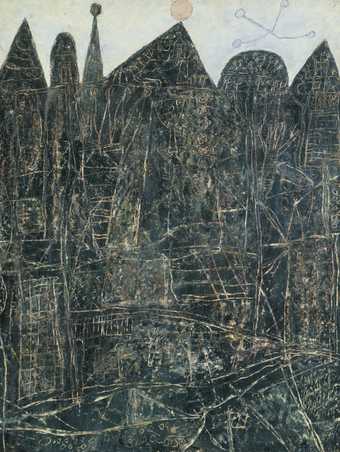

Author and artist Mark Haddon, , best known for his novel The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time, came to to look at The Busy Life 1953 by Jean Dubuffet.

This work belongs to a series that Dubuffet called beaten pastes because the main paint layer resembled butter, into which he scratched the graffiti-like figures. In this film, Haddon shares his love for Dubuffets technique: a celebration of mark-making and texture.

I’m standing in front of Jean Dubuffet’s painting The Busy Life, painted in 1953, which is one of my favourite paintings in the Tate, by one of my favourite painters. I guess the first thing you notice when you see it, is this wonderful naïve playground tumble of figurers.

Complete disregard for anatomy, perspective, even for up and down. Rather like the Outsider Art that he was fascinated by and collected – art by naïve painters, art by the mentally ill. And I guess if you don’t really understand that kind of painting, you could look at it, and you could say – you know, a child could do that – unless you’ve actually picked up a paintbrush yourself and actually tried to do it. It’s really, really hard to access that freedom, to step outside the tradition.

I mean, his early paintings were kind of extremely competent in the art world sense, but it takes a great deal of skill to put that to one side, to untie yourself and learn how to paint like this, which is like a child, but not like a child. The second thing I guess you notice is the wonderful scruffito technique he uses.

There’s a brilliantly random, brightly coloured ground with this white paint palette-knifed all over the surface, and then he scratches through it – so the lines are literally dug into the surface. So you can’t really tell what is line and what is colour.

Certainly the underpainting, the coloured underpainting, was, I think, left to dry, and then the white paste was spread over it; but I think in places he has taken the paste off and done it again. One of the interesting things about this is, this is purely done in oils, and one of the really radical things about a lot of Dubuffet’s paintings, and the thing I love, and the thing that makes me want to reach out and sort of run my hand over the surface, is the fact that he used oil repellants, he used sand and other gritty mixtures, which he mixed in with the oil paint to create a surface you don’t see on anyone else’s paintings.

This painting always makes me think of something that David Hockney said, which is that whereas in a photograph there is no time, in a painting it is always a record of what the painter’s hand did over a period of time. Often that’s very moving, if you look at a portrait of someone, the painter’s hand has caressed that face for, you know, weeks, months, sometimes years.

We don’t see the maker’s hand doing things in paintings before the nineteenth century, usually, because most painters aspire to a kind of sheen. With the Impressionists you start to see people celebrating the mark making, celebrating what they have done with their own hands when they are making a painting. And it reaches its apogee, I guess, with the abstract Expressionists, where the paintings aren’t really about – they are a record of how the painting was made – and if you look at a Jackson Pollock, you can dance with him round the floor of that big barn studio of his. I think I’ve seen children reacting to this painting; and they do think it’s a kind of playground event, some kind of carnival, or jumping, tumbling game. But I think it’s the painting of a man who has watched street scenes over a long period, and has put them all together – all these joyous moments. The way a hand puts time into paintings is both moving and really, really important.

You are always looking at this painting. You are very conscious of it being of something, but your eye is always brought back, always brought back to the surface. And always brought back to the time and the action and the whole adventure of its making. Art is always about taking something impermanent, about taking lines, about colours or words, and giving them meaning in such a way that we are still reading them, we are still looking at them, 500, 1000 years later. And if you stand really close here, and if you look at the surface, it’s almost like you can hear Jean Dubuffet’s ghost talking, saying, look, I’ll take you by the hand, and I’ll show you how you do this. And this is how you cheat death; this is how you move people who won’t be born for another 500 years.