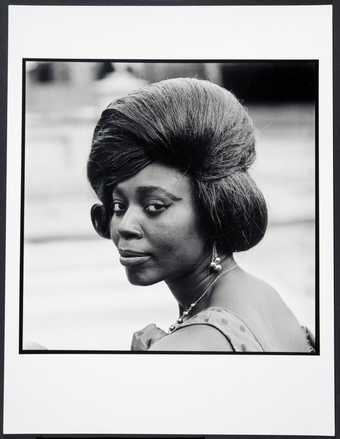

James Barnor

Eva, London (1960s, printed 2010)

Tate

James Barnor was born in 1929 in Accra, Ghana. With over six decades of experience, Barnor is cited as being one of the most influential African photographers of all time. Barnor started out as a police photographer. He then went on to be a photographer for The Daily Graphic and Drum Magazine. Through this, he provided us with imagery that harnesses the swinging sixties in the UK and Ghana from a uniquely Black perspective. He is also credited with capturing the daily experiences of post-colonial Ghana.

Osei Bonsu, Curator of International Art, visited him in London to discuss his life and work.

OB: Did you grow up around photographers?

JB: Now that I've come to think of it, I haven't come across anybody who had so many photographers in his family. My mother's older brother was a photographer. I think his brother, too. He was a teacher, but he also had a camera, and he used to take photographs. We had another uncle from Osu. He used to come to our house in Accra, but he was also a professional photographer. Then Mr. J.P. Dodoo, who was a cousin, was practicing as a photographer.

OB: Could you tell us about your first camera and your first time really experiencing photography?

JB: Oh, that was really exciting, when I got the camera. Mr. Emmanuel Odonkor-- He was the craft teacher, or basket teacher [at the school Barnor used to work at]. He gave me the camera. I don't know whether he had heard that I contemplated being a photographer, but he gave it to me. It was a small baby Brownie 127 camera. Nobody showed me how to focus, how to go in close, how to take a big view or a small view. I just started.

OB: Do you have a memory of the first picture you ever took?

JB: I can only recollect a picture that I took first. I was at the school, and the students were on break. I took a picture of a girl with all the chairs and a lot of things around. Later, as I used the camera a bit, I took a picture of a bus, with the conductor serving the passengers. That was a bit better.

OB: You'd undertaken an apprenticeship with your cousin, J. P. Dodoo, who was a well-known portrait photographer. How did that partnership come to be?

JB: I used to be sent to J.P. Dodoo many times because he was local. Somehow, my uncle, my mother's brother, retired before I left school. I didn't have anything to do with his photography. Then, I didn't even intend to go and understudy him, but I think somehow I must have mentioned that I wanted to go to my cousin, J.P. Dodoo, to learn photography.

OB: What role do you think photography played in Ghana at the time? How were people experiencing photography?

JB: As you know, it was an old colonial culture. People went to the photographer when they went to church, or they had weddings, or they had new clothes, or they had friends, something like that. When anybody came, you put the backdrop, and then arranged props, and the person would go and stand there. In the studio we used a half–plate camera, a big camera. In photography it's called a field camera, that takes plate negatives.

We were using plates before sheet films were developed, so that when it falls, it doesn't break. It's not as heavy as a glass plate, but the sensitivity was the same. Even in those days, the speed of the film was very slow. It was a slow beginning.

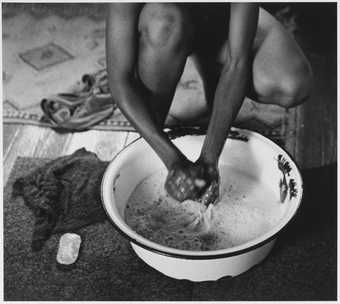

OB: You started off your career as a freelance photographer working in your aunt's home. Could you talk about that first space where you were developing photographs?

JB: I started because I had the love for cameras. I was familiar with roll films, as well as the plates. At work, I would be working with the plates, but when I came home, I develop and print roll films from my friends who were amateur photographers. I developed in my aunt's room, I made it as dark as possible, and I would develop. In the same darkroom, I arranged my developer, and all the chemicals on the table and develop and hang the films in my room. The next morning, they were dry. I got up in the morning and would start printing.

OB: You started your own studio in 1953. How did you come up with the name Ever Young?

JB: I remember that while we were at school, we had an extract from the English composition about somebody who changed old people to new. It goes like this, "Iduna, the beautiful young Goddess of the Norsemen lived in a pretty grove called Ever Young. She had a golden casket full of the most wonderful apples. A hero might come tired and weary, and Iduna would give him an apple, and as soon as he had eaten it, he would feel fresh and young again."

After some time, the teacher would give us questions to see whether we understood the story, what we learned from it. What sticks in our mind about the story. One of the questions was, "Give this extract your own name." It was Iduna's grove, but because Ever Young was mentioned, and it meant more ever young than anything, I chose Ever Young. This was 1945, before the end of the war.

I actually wrote it as a signboard right from the early '50s. There is a picture of that signboard. In fact, when I found it, I thought I'd come across gold.

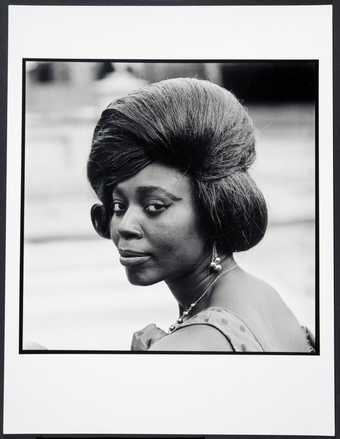

James Barnor

Flamingo cover girl Sarah with friend, London (c.1965, printed 2010)

Tate

OB: How did you get involved in The Daily Graphic and Drum Magazine?

JB: Someone from The Daily Graphic went to the one who trained me, Mr. J.P. Dodoo. He [Dodoo] said, "Oh, I don't do this type of photography. I do studio work, but I know somebody who does it." They came to my studio. My father said, "I should bring this white man to you." Then he told me this is his mission, they're starting The Daily Graphic, and then they want a photographer. I said I'm interested. He said, "Have you got anything to show?" If I'd known before, I would have selected my best features. I had that box of photographs, and I showed it to him.

He looked through and he said, "Not quite, but we'll train you." Of course, he didn't stay long.

While he was in Ghana, we went about together. We went to assignments, and he showed me how he developed in his hotel by using a developing tank, something which helped me, because normally I hadn't seen the tank before. He took me into the castle for the first time, Osu Castle, where only English people lived and worked.

The introduction of The Daily Graphic and the daily coverage of newspapers and the way that the press handled stories and so on, it made a big change in the lives of Ghanaians.

OB: What sparked your decision to move to London in 1959?

JB: I thought I wasn't complete. Meeting the world press and other things, I thought I'd go and learn more or go and learn to use better cameras or see how better cameras or see how bigger darkrooms were occupied and so on. That's always in the mind of colonial people. Go to England to learn more or to see how the place is, but I couldn't leave my work and go. As I said, during the independence I saw improvement, that room for improvement.

A year later, WUS (the World University Service) arranged a seminar from Canada to Ghana to study the effect of independence on the lives of newly freed colonies. I happened to know about it. I started covering it and in the end, I went and stayed with them at Legon and set up my darkroom there.

Finally I asked if London would be all right for me. They said London is a place for you. They said with your past experience and your knowledge, if you can get chance to get in, the sky will be the limit. That was what gave me the impetus to try and get a passport and find my way there.

OB: How did you feel when you arrived?

JB: On the 1st of December, I arrived in Liverpool and then I went by train to London. It was very cold. Sometimes, you're so excited that you don't feel the cold. I was taking care of a Jamaican who was looking after the house for a British citizen who had retired and was living in Ghana. I met him, he said, "Oh, this man he will, he will fix you up in my house.” When I went, he said, “Oh, the place is full. You can stay with me if you like.” Right from the word go, I was treated or taken as if I was already living there.

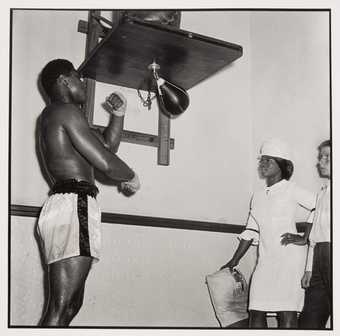

James Barnor

Muhammad Ali training, Earl’s Court, London (1966, printed 2010)

Tate

OB: One of the big influences, while you were in London was Dennis Kemp. What impact did the photographer have on you?

JB: Dennis Kemp is the influence that changed my life, changed everything, and more or less paved the way, and also made me get into a circle where I didn't come across race differences or anything at all.

I met Dennis when he asked to see me, this is what he does. He couldn’t get me a job, but he could get me somewhere to live and something to eat, but his job was to teach photography or talk about photography. I jumped at it. Straight away, he put me in London School of Printing. It was in Holborn about 15 minutes walk from where we lived and I was doing two evenings a week.

OB: Whilst in London, you started to experiment with colour photography for the first time. How did you learn how to use it?

JB: I started exposing, using colour film, taking pictures that I like in transparencies which were developed by Kodak, and also getting into the colour processing laboratories, starting to process color and print color.

My mind was quite different. I jumped a bit when I was getting used to it. Then Dennis decided, you must go to school. Why? I didn't argue. I applied to a school.

OB: Where did you end up going to school? What was the process like?

JB: Somebody in the Color Laboratory Dennis had contact with – He knew about the Medway College of Art in Rochester and he gave me the address. I applied.

I applied using the lab as my address so that I could get the letters quickly. Straight away, I was called for an interview. When I went, the master looked through my work. He took me to the Principal, and he said, "James hasn't a got GCE [General Certificate of Education], but I will take care of him." I got in.

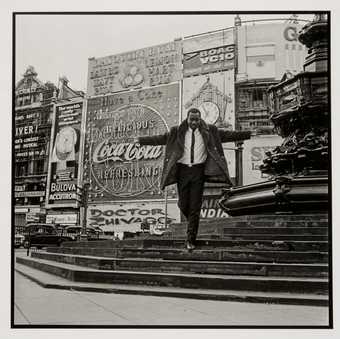

James Barnor

Mike Eghan at Picadilly Circus, London (1967, printed 2010)

Tate

OB: What was your experience taking portraits in London for the magazines?

JB: When I'm taking pictures of portraits, I don't like it to be just a plain portrait that you don't know. It should tell where you are; either a post box or a London telephone box or the pigeons or something. Trafalgar, Nelson's Column or something like this.

People look at it and they wonder, "How is it that the place has changed like this?" "How did you manage to do that?" If you go there now, I think the place is full of people but somebody will ask, "How did you manage to take a picture of one person and nobody in Trafalgar square?"

OB: Did you have good relationships with the models you worked with?

JB: Yes, my relationship with the models was organic. You got to be flowing with the model in order to get the best of the model. Whatever you do to get what you want or for her to show her best.

OB: You went back to Ghana in 1969 as a representative of Agfa-Gevaert after a decade in England and you set up the country's first colour processing facility. Could you talk about that time of return?

JB: Yes, I got a hint that they’d lost a photographic manager in Ghana, so I should apply. Eventually, they called me for an interview and I passed the interview. “You go because we arranged a course for you because you are going to be a representative, and you should know what we are manufacturing, or what you are going to sell, and how you are going to order them and control them.You are going to be in charge."

That's how it went. At that time, Agfa-Gevaert wanted somebody with a colour background because colour was in at the time. It's a bigger company handling different things including x-ray films and reproduction printing facilities, as well as photography, and chemicals, and cameras. They organised a course for sales reps to go through. I had to go through that as well.

James Barnor

Eva, London (1960s, printed 2010)

Tate

OB: What was it like to move back to Ghana with all of these new experiences and techniques?

JB: Even when I arrived, I don't think the manager believed that a Black man could do colour. That's why I arranged the colourful things, and photographed them so that when they were developed on the premises, we saw the colours right.

OB: Tell me something about what you are proud of, because you look back on this incredible body of work that spans decades and in a way has become part of Ghana's history. What aspects of that contribution to photography are you most proud of?

JB: In Ghana, I should have been recognised as a photographer and something should be done with my work after the 10 years of the work that I did there. But nobody. It's only by chance that a museum in Paris acquired some of my work and at one time they asked me to come and explain about the pictures and the ambassador of Ghana was invited. When she saw me and heard what I said about the pictures and my work, made her realise that, no, this man should be recognised by Ghana.

The photographers in London, the Black photographers, think of me as a leader and I'm very proud of it. If the Ghanaians, too, get over their economic limitations and they are free to use photography and get the benefit of photography, fine. That's what I think of.

OB: What is it about the power of photography that you think is so enduring?

JB: It is a learning tool as well as an information tool. Any profession, any walk of life needs photography. A teacher with a phone taking photographs can use this to show his students. A tailor can copy something and later use the design. A detective would it too.

There is what they call clinical photography or medical photography, that's there. A lawyer needs something for evidence and he wants a photographer. You don't always have to employ a photographer, so there is no need to go to a photography school, but there is the need for you to use photography. It's so important now. You can't leave photography out in any part of your life.

Even the person who collects the dustbin has something that he likes or he doesn't like that he would like to record - to report to the authorities to make a change. Or it could be for the police to use as evidence.

OB: If you had to give advice to a young photographer who was starting out today, other than about the question of education, just about what it means to be a photographer, what would you say is the most important lesson?

JB: Go in with a view that you're going to stay there all your life. Get the equipment to start work, love the work and make it worth your while, because I wouldn't change it for anything. I wouldn't like to go and be a lawyer. I would like to be a photographer if I already know it, and I can get the chance.

OB: How do you want people to look at your work?

JB: That, I leave it to them. I leave it to them.

Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor