The Artist in his Studio 1964–5

Courtesy Ibrahim El-Salahi

Who is he?

Ibrahim El-Salahi is a Sudanese artist who was born in 1930 in Omdurman, Sudan. He currently lives and works in Oxford, England. He combines painting and drawing often using motifs from African, Arab and Islamic art as well as Western references.

He completed his degree at the Slade School of Art in London and then returned to Sudan to teach in Khartoum. His time at the College of Fine and Applied Arts, there, sparked a movement now known as the Khartoum School of which El-Salahi was one of the founders.

El-Salahi also spent a number of years working for governments. He began by establishing the Sudanese Embassy’s first ever Department of Culture and then went on to work for the Ministry of Information in Qatar. In between these roles, El-Salahi spent just over six months wrongly imprisoned without trial in Sudan. The hardship he endured there has informed much of his later work.

El-Salahi has been recognised as a leading modernist figure and had a retrospective at Tate Modern in 2013.

Ibrahim El-Salahi

Vision of the Tomb 1965

Museum for African Art, New York

© Ibrahim El-Salahi

How did imprisonment inform his work?

I work on a new piece, and because I do not know what shape it is going to take, I add pieces. This is something that I learnt in jail. In jail, if someone was found with a pencil or paper, then something terrible would happen. So I used to have smaller sheets of paper and I used to draw small embryo forms. Then I added little bits and I used to bury it in the sand outside the cell, just for fear of solitary confinement for 15 days. Anyway, when I came out, I recalled the same idea of making… Each piece [of the work] has to be framed separately, because it’s an embryo of an idea that I’m not aware of completely. Then when it grows together it creates a whole.

Interview with Mark Rappolt, Art Review, April 2015

What are his key works?

The message that I put in The Inevitable was that someday, sooner or later, people will rise against tyranny, and that is up to them as a group, and they have to have what it takes, what is needed, to work together and to have force enough to make the changes necessary. The message is embodied in the work itself. (Interview with Mark Rappolt, Art Review, 2015)

Watch this film to find out more:

In Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams 1 of 1962-3 El-Salahi captures the fleeting, and often dramatic, moments when memory and dreams, past and present collide. In the following film he discusses the making of the piece.

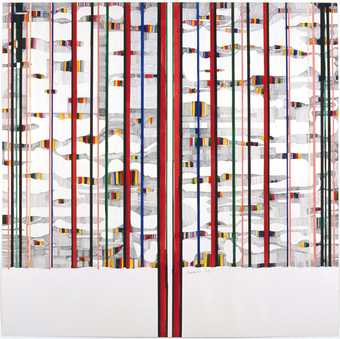

Ibrahim El-Salahi

The Tree 2003

Collection of the artist © Ibrahim El-Salahi

The Tree series are a group of colourful paintings inspired by the english countryside, reminiscent of the haraza trees that grow along the Nile in Sudan. The works appear to reference Islamic imagery, which uses geometric shapes to represent the order of the world. El-Salahi paints recurring vertical lines to convey woodlands or individual trees:

There is no painting without drawing and there is no shape without line… in the end all images can be reduced to lines.

Ibrahim El-Salahi interview with Salah Hassan

What the critics say

He is now hanging where he belongs, next to Karel Appel, but also Robert Motherwell, and in front of Dorothea Tanning.

Lara Pawson quoting Chris Dercon, Frieze 2013

El-Salahi is a born story-teller. He is full of stories when he narrates, writes or draws, not to mention the tales that are told about him.

Hassan Musa, Tate Etc. issue 28, 2013

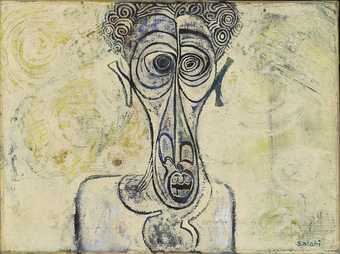

The light side of life mingles with the sinister in El-Salahi’s paintings. He seems to work from a place of deep conscience and intuition.

Hande Eagle, Aesthetica Magazine

Ibrahim El-Salahi Self-Portrait of Suffering 1961

Iwalewa-Haus, University of Bayreuth, Germany

© Ibrahim El-Salahi

El-Salahi in quotes

Working in a democracy is a lasting experience; working under a dictatorship is an incentive for doing something – sometimes you can be afraid of the consequences, but sometimes you have to say you have a definite message.

Interview with Mark Rappolt, Art Review, April 2015

A picture is no more than a mirror, a vehicle that takes one back to one’s self, to turn one’s sight inwards to find the Self within and begin to meditate.

Ibrahim El-Salahi, Memoirs, unpublished manuscript, 2005

There are three people to address [when making an artwork], the self, the ego; unless you satisfy that ego, no work will come out at all. Second are the people in your own culture, family or neighbourhood. And third are all, human beings, wherever they might be.’

TateShots: Ibrahim El-Salahi