Tropicália was a creative movement that originated in the late 1960s in Brazil.

Encompassing music, art and writing it celebrated Brazil’s culture and people. It was also a protest movement against the lack of freedom experienced under the oppressive regime of the military government.

Artist Hélio Oiticica played an important role in defining the movement.

The Origins of Tropicália

Tropicália was a creative explosion and it was a political movement wrapped into one.

Jill Drower, author and friend of Hélio Oiticica

Tropicália is perhaps best known as a movement in music.

It was the name of a song by celebrated Brazilian musician Caetano Veloso. It was also the title of an LP released in 1968 featuring experimental musicians such as Gilberto Gil, Gal Costa and the psychedelic band Os Mutantes.

But although often discussed in relation to music, visual art was an important part of the movement.

The name ‘Tropicália’ was coined by artist Hélio Oiticica. He used it for the title an artwork he first exhibited in Rio de Janeiro in 1967. The word was intended to play on stereotypes of Brazil as a tropical paradise.

After Caetano Veloso borrowed the title for his song, it began to be used to define the counter-culture movement.

Helio Oiticica's Tropicália installed in Rio de Janeiro in 1967 © Projeto Hélio Oiticica

WHAT WAS HAPPENING IN 1960S BRAZIL?

In Brazil in the late 1950s and early 1960s there was a sense of optimism and excitement.

A new president, Juscelino Kubitschek, had just been elected. He promised progress and stability for a country that had been unstable for decades. The arts flourished as musicians, writers and visual artists explored new ideas and approaches to creativity. Visual artists experimented with abstraction and interactive art, while musicians were busy inventing a whole new form of music by mixing Brazilian samba with jazz and rock-and-roll.

But in 1964 a military coup, backed by the USA, brought an oppressive right-wing government to power.

The new government was determined to halt what it saw as left-wing dissent and the rise of socialism. It began cracking down on political expression and student protests. But their efforts at stifling liberties had the opposite effect. Musicians, artists and writers were even more determined to fight for freedom of expression through creativity.

Evandro Teixeira, Police repression of a student march at Edson Luís, Candelária, Rio de Janeiro 1968 © Evandro Teixeira

INTERACTIVE ART

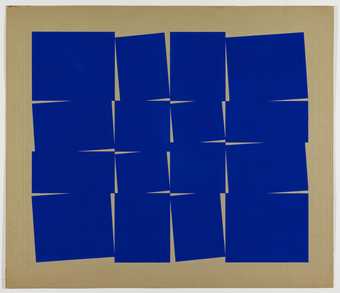

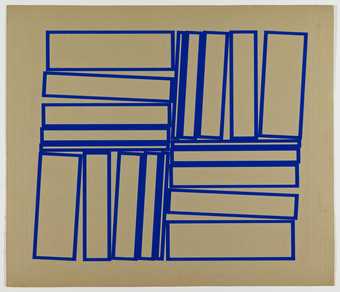

In the mid 1960s, Hélio Oiticica began to move away from painting on flat surfaces. He started to make flexible objects and structures which he called Parangolés.

The Parangolés included capes and banners. They were artworks that people could interact with. Made from layers of painted fabric, plastic, mats and ropes, they were designed to be worn or held while dancing to the rhythm of Samba. Some of the capes included poetic or political messages that were revealed depending on how the wearer wore them or how they moved.

One of Hélio Oiticica’s Parangolés © Projeto Hélio Oiticica

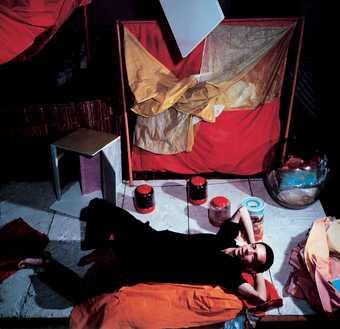

Tropicália, first exhibited in Rio de Janeiro in 1967 is the artist's best known participatory work.

On one level it is an ironic take on the idea of Brazil as a tropical paradise. Sand, palm plants, parrots and colourful makeshift structures suggest a tropical stereotype of Brazil.

Hélio Oiticica’s, Tropicália, Penetrables PN2 ‘Purity is a Myth’ and PN3 ‘Imagetical’ 1966–7 © Hélio Oiticica

But this fake, fun world also has a radical political undercurrent. The structures were inspired by the favelas – the slum dwellings of Rio da Janeiro. In reaction to the strict regime of Brazil's military dictatorship, Oiticica advocated the radical potential of simply hanging out.

Everything that Hélio was doing was like the most radical response to the lack of liberty and the lack of respect for liberty.

Caetano Veloso, musician

Visitors to Hélio Oiticica's installation of Tropicália at Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1969 © Guy Brett

Tropicália was designed to activate the senses of visitors (or ‘participators’ as he preferred to call them), to stimulate feeling and expression.

Visitors are invited to walk barefoot in the sand, watch TV or relax. They can interact with the installation however they wish. Free expression and freethinking are encouraged!

What is the legacy of Hélio Oiticica and Tropicália?

He was pushing the boundaries of what art could do and how it could free people.

Michael Wellen, Curator, International Art, Tate

Hélio Oiticica made art that was participatory and inclusive.

The audience that came to his exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1969 were not the usual gallery visitors. They included businessmen who wanted to relax on their lunch breaks and local children who played in the sand. Ensuring that everyone can get involved, while at the same time raising awareness of issues relating to freedom and society, defines the work of Oiticica.

Visitors to Hélio Oiticica's installation of Tropicália at Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1969 © Guy Brett

Visitors to Hélio Oiticica's installation of Tropicália at Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1969 © Guy Brett

Many artists working today in the twenty-first century are increasingly making art that is similarly participatory and socially aware. This is often referred to as socially engaged art or socially engaged practice.

Artists such as Theaster Gates, Tania Bruguera and Assemble collaborate with groups of people in order to give them a voice, help them improve their lives, or simply share ideas and create art with them. People are at the centre of the work. Socially engaged practice is also often associated with activism because it highlights and responds to social and political issues.

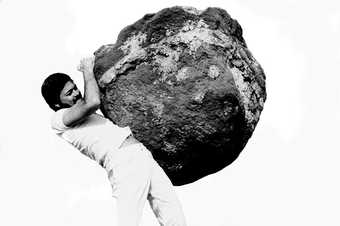

When he died in 1980 at the age of just 42, Hélio Oiticica left an extraordinary body of work that was innovative, intelligent and engaging. But perhaps his most important legacy was that he put people at the centre of art.

His [Oiticica’s] concepts of interactivity, coexistence and marginality are fundamental to what is happening now in art and in the world.

Ernesto Neto, 'Be an outlaw ... be a hero' Tate Etc. 2007

Hélio Oiticica © Projeto Hélio Oiticica