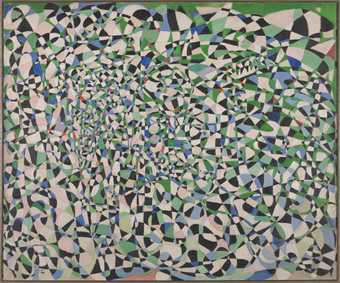

Fahrelnissa Zeid Untitled c.1950s Tate © Raad bin Zeid

Fahrelnissa Zeid (1901–1991) fused modern European approaches to abstract art with Byzantine, Islamic and Persian influences to create a unique visual vocabulary. It is astonishing that an artist of such force and originality should have been practically forgotten, particularly in London and Paris where she was a prominent figure in the art scene for decades.

This exhibition charts Zeid’s development towards abstraction and reveals how she later abandoned this in favour of an experimental amalgamation of painting and sculpture before finally returning to portraiture.

Zeid was born into an elite Ottoman family in Istanbul in 1901. She was one of the first women to receive formal training as an artist in Turkey, before continuing her education at the Académie Ranson in Paris in the late 1920s. Her second marriage, to Iraqi ambassador Prince Zeid Al-Hussein, in 1935 brought diplomatic duties and relocation to Berlin and then Baghdad. Notebooks record the development of her visual style, which flourished on her return to Istanbul in the early 1940s. This exhibition begins in earnest with her paintings from this period. Little survives of her earlier work.

Zeid went on to have an exceptional career, living and working in a wide range of geographical and cultural contexts as indicated on the opposite wall.

Room OneWays of living

Zeid began drawing and painting at an early age, inspired by her mother and her older brother, who dropped out of Oxford University to study art in Rome. The earliest work in this exhibition is a delicate portrait of the artist’s grandmother, painted in 1915 when Zeid was fourteen years old.

Although Zeid continued to draw and paint from her teenage years on, she did not exhibit her work until the early 1940s. On her return to Istanbul during the Second World War, she was finally able to concentrate on her art. There she began to interact with the avant-garde d Group who championed new approaches to painting and believed in making art available to ordinary people. This gave Zeid the confidence to stage her first solo exhibition in her apartment in the fashionable Maçka district of Istanbul in 1945.

Her subject matter at this time ranged from interior scenes and still lifes to nudes, portraits and landscapes. Vibrant colour and black line – which would become signature aspects of her later style – are evident in most of her works from this period.

Fahrelnissa Zeid Fight Against Abstraction (Dispute contre l'Abstraction) 1947 Istanbul Museum of Modern Art Collection, Eczacıbaşı Group Donation (Istanbul, Turkey) © Raad bin Zeid © Istanbul Museum of Modern Art

Room TwoFight against abstraction

At the end of the Second World War, Zeid’s husband, Prince Zeid Al-Hussein, was appointed ambassador of the Kingdom of Iraq to the United Kingdom and the couple relocated to London. Here Zeid’s work underwent a radical transformation. Despite many diplomatic obligations and social engagements, Zeid continued to paint, turning a former maid’s quarters in the embassy into her studio. Although based in London, she also rented a studio in Paris and divided her time between the two cities. Zeid recounted how she began to feel at ‘ease as a painter’ at this moment:

As long as I had lived and worked in Turkey, I had seemed to distrust my own artistic initiatives. I was too isolated, too unsure of myself. Now I feel that I am at least understood and accepted, whether in London or in Paris, as an artist rather than as a kind of freak.

In post-war Paris, abstraction was taking hold. The painting Fight against Abstraction 1947 reveals Zeid’s internal struggle between representation and abstraction. She went on to develop her own kaleidoscopic visual language, drawing on both the specificities of her cultural background and her exposure to European art history and contemporary art.

Room threeResolved problems

By 1948 Zeid had established her own abstract style. Over the next fifteen years, living between London and Paris, she produced monumental abstract paintings which reveal her synthesis of a wide range of influences, from nature and Islamic architecture to Byzantine mosaics and stainedglass windows. Her determination and energy are evident in these crowded compositions, realised with rapid brushwork.

Photographs of the crammed studios in which she worked show unstretched canvases filling the walls from floor to ceiling and sometimes wrapped around the corners of the studio. She nailed other paintings directly to the ceiling and arranged painted stones on any available surface.

Zeid completed the large canvas My Hell in 1951 after an episode of illness. In Paris she exhibited alongside artists associated with the Nouvelle École de Paris, a group of painters loosely connected with influential curator Charles Estienne. In London she held salons at the embassy, gathering around her artists, writers, actors and curators. Her solo exhibition at the Galerie Dina Vierny in Paris in 1953, which transferred to London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1954, firmly secured her place in the art scenes of both cities.

Room fourThe influences of nature

In the 1950s Zeid bought a holiday villa on the Italian island of Ischia. There, she began to move away from the strong black lines that had underpinned her abstract paintings, experimenting with a looser and more lyrical style, while continuing to make a large number of drawings and prints. Ordinarily Zeid’s husband returned to Baghdad in the summer to relieve his nephew King Faisal II of official duties, but in 1958 Zeid persuaded him to travel to Ischia with her instead. While there, a coup d’état in Iraq led to the assassination of the entire royal family. The couple were given twenty-four hours to vacate the Iraqi embassy in London, a turn of events that abruptly halted Zeid’s career as a painter and hostess in London. She later commented:

It is as if I had suddenly become afraid of colours and of life. Instead of the brilliant kaleidoscope that once seemed to surround me, I can only perceive, all around me, a winding labyrinth of hard and heavy black lines … It is as if I had been brutally brought back to the very start of my career as an artist and were now forced to test again the validity of every device that I have ever used.

Room fiveLate style

At the age of fifty-seven, Zeid cooked a meal for the first time. The enforced domesticity that resulted from the sudden end of her ambassadorial lifestyle offered her an unexpected source of inspiration. She started painting on turkey and chicken bones as she had previously done on stones, later setting the bones in resin. She displayed these sculptures on motorised turn-tables so they could be seen from all sides, with lighting that emphasised the translucent quality of the material.

Freed from diplomatic responsibilities, Zeid gradually returned to painting and by the mid-1960s had begun to paint portraits of those closest to her. In 1969 she and her husband left London to live permanently in Paris and a year later Prince Zeid Al-Hussein died. Zeid moved to Amman to be near her son and his family in 1975. In Jordan she built up a new social and artistic circle, mentoring a group of younger women in abstraction while focusing on portraiture herself, choosing friends, family members and students as sitters. Her daughter described this as the ‘most creative, productive and rewarding period of her life’. Zeid continued to paint well into her eighties and died in Amman in 1991.