David Hockney (born 1937) is one of the most popular and widely recognised artists of our time. After first coming to public attention in 1961, while still a student at the Royal College of Art, he went on to produce some of the best-known paintings of the 1960s.

This exhibition, a survey of almost sixty years of Hockney’s art, offers the first opportunity to see those classic early paintings alongside subsequent work in a variety of media. It spans from paintings made as a student in London through 1960s Los Angeles, the reorientation of his practice in painting and photography in the 1980s, a decade of Yorkshire landscapes, and on to the newest works made since his return to California in 2013.

From beginning to end, running through all the different types and periods of work is Hockney’s principal obsession with the challenge of representation: how do we see the world, and how can that world of time and space be captured in two dimensions? The exhibition is largely arranged chronologically but the first room presents works from different periods which exemplify the ways in which Hockney has played with the conventions of picture-making.

Room OnePLAY WITHIN A PLAY

Hockney has frequently made work which questions the conventions of picture-making, challenging the protocols of perspective, for example, or highlighting the assumptions required for a viewer to read a picture. That is to say that many of his pictures are about making and looking at pictures.

Play Within a Play 1963

Based on a photograph of the artist’s friend, John Kasmin, pressing himself against the glass door of his gallery, this work plays with ideas of reality and illusion. The figure stands in front of a curtain in an impossibly shallow space; while he and the backdrop are painted directly on the canvas, the points where his body touches the glass are made with paint on a ‘glass’ panel mounted on the painting: what appears real is an illusion; what appears to be an illusion is actually there.

Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices 1965

The title highlights that all art depends upon artificial devices, illusionary tools and conventions that the viewer and the artist conspire to accept as descriptive of something real. Here a conventional figure sits encircled by bits of abstract art appropriated from the work of Paul Cézanne and Kenneth Noland, among others.

Rubber Ring Floating in a Swimming Pool 1971

Hockney has often played satirically with abstract art. Here the red circle on aquamarine recalls the work of several abstract painters of the late 1960s. In fact this image is a close recreation of a photograph of a floating rubber ring as indicated by the depiction of the pool’s stone surround and the bubbles of its water inlet.

Kerby (After Hogarth) Useful Knowledge 1975

The convention of one-point perspective has long been a concern for Hockney who embraced cubism’s ability to describe a subject better through its introduction of an element of time and movement. Here he remade an image by William Hogarth which shows how perspective can make a scene look realistic while allowing impossible things to occur, typified by the distant figure of a man lighting his pipe from a candle in the foreground.

Model with Unfinished Self-Portrait 1977

Hockney has made numerous works which take the process of picture making as their subject. Here Hockney’s boyfriend is shown asleep in the studio; the figure in the background is not Hockney but a canvas depicting the artist; yet, the curtain which is part of that unfinished painting seems also to extend across the edge of another work with its back towards the viewer.

4 Blue Stools 2014

Hockney used digital photography, stitching hundreds of images together, to create a scene which, like Kerby, initially appears realistic but is gradually revealed to be impossible both in terms of the exaggerated recession of the space and because several figures appear more than once.

Room twoDEMONSTRATIONS OF VERSATILITY

During the period 1960–62 while studying at the Royal College of Art, Hockney came into contact with a range of influences. The works in this room capture his early interest in human relationships, landscapes and places or situations real and imagined.

Initially, Hockney experimented with abstraction, making a small group of free-flowing paintings in which symbols of personal desire began to emerge. As his interest in different pictorial conventions and concepts of space developed, he employed graffiti, cryptic codes, phallic shapes and freehand writing to suggest themes of sex and love. Here, child-like scrawled bodies, identified by numbers corresponding to letters of the alphabet, are situated in areas of spatial ambiguity, offering recognisable representation while drawing attention to formal qualities such as texture and brushwork.

Hockney showed four paintings under the title Demonstrations of Versatility in the 1962 Young Contemporaries exhibition. Playing with different realities and modes of representation, they assert Hockney’s declaration that style can be consciously chosen or dispensed with and several styles included in a single work. As he noted, ‘I deliberately set out to prove I could do four entirely different sorts of picture like Picasso.’

Room threePAINTINGS WITH PEOPLE IN

In the two years between leaving the Royal College of Art and his first visit to Los Angeles in 1964, Hockney’s painting started to swing from an art of imagination, of plays with the artistic conventions of abstraction and representation, towards an art that would be more observational. His subject matter remained broad, as did his continued quotation of artistic styles.

His first exhibition, Paintings with People In, at the Kasmin Gallery in London in 1963 signalled the shift in Hockney’s art and focused on a series of paintings titled Domestic Scenes. Where the paintings of 1961 had celebrated gay desire, these portraits of relationships between couples, by their very domesticity, normalise that desire into images of companionship.

Illusion and artifice remained a strong feature of his work of this period, typified by paintings including a curtain. The curtain frames the passage of light, identifying the stage of Hockney’s painting as a theatre of representation. In February 1964 Hockney first visited Los Angeles, which – through Hollywood – was a place of pictures and dreams made real. It was, as he described it at the time, his ‘promised land’.

Room fourUNBATHER

From 1964 Hockney lived in the Santa Monica area of Los Angeles and set out to paint that city. He loved its open spaces, where he found a clarity and geometry in the modernist lines of office blocks, the mid-century designs of the houses, and the pattern of sprinklers on people’s lawns.

Even before he arrived, Hockney thought of Los Angeles as ‘sexy’, its climate encouraging a culture of handsome, athletic young men that the artist had first known through erotic magazines imported to Britain from California.

Questions of depiction continued to absorb him. How could a painter capture the transparent qualities of glass, or of water which was constantly in motion?

With these works, also, Hockney satirised the abstract art that was then dominant: the borders around the paintings emphasise the artificiality of the scenes they depict; the simplified forms become comparable with abstract compositions. Specifically, Hockney’s laboriously painted splash might be seen as a dig at the macho spontaneity associated with abstract expressionism, and the seemingly realistic description of office buildings as a skit on the modernist grid that was coming to the fore in minimalist art.

David Hockney

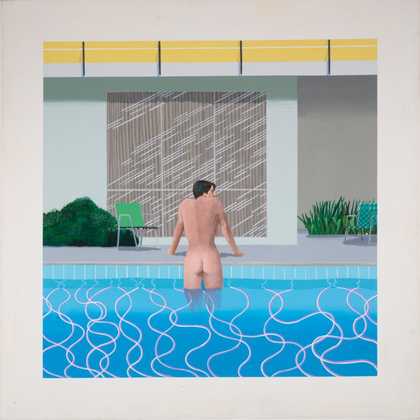

Peter Getting Out of Nick's Pool 1966

Collection Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© David Hockney Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt

Room five TOWARDS NATURALISM

Towards the end of the 1960s, naturalistic representations of the human figure became a key element in Hockney’s work. Drawn to the psychological and emotional implications of two figures within enclosed settings, Hockney worked directly from a circle of friends and acquaintances in a series of double portraits that capture their intimate and often complex relationships. Near life-sized, these carefully staged compositions combine informal poses and settings with the grandeur and formality of traditional portraiture. Almost all these works are painted in acrylic, which dries quickly and cannot be scraped off the canvas, thus demanding a greater degree of planning and meticulous application. This process, with its greater capacity for scrutiny and observation, meant that Hockney could work from photographic studies to sketch out overall compositions but he chose to paint his figures from life.

A series of still lifes and landscapes enabled Hockney to exploit the qualities of acrylic paint to achieve a naturalistic rendering of water, glass and transparency, furthering his interest in the contrasts between flatness and depth, inside and outside, naturalism and artifice.

David Hockney

Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy 1968

Private Collection © David Hockney

WHO’S WHO?

Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy 1968

English novelist and playwright Christopher Isherwood (right) and his partner, artist Don Bachardy, in their Californian home.

American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman) 1968

American art collectors Fred and Marcia Weisman outside their modernist Los Angeles house with sculptures by British artists Henry Moore and William Turnbull in the garden.

Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott 1969

The figure in the centre is Henry Geldzahler, friend of Hockney and at that time Curator of Contemporary Art at The Metropolitan Museum, New York. His partner, painter Christopher Scott, looks on.

Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy 1970–71

Fashion designer Ossie Clark and textile designer Celia Birtwell with their cat in their Notting Hill home shortly after their wedding.

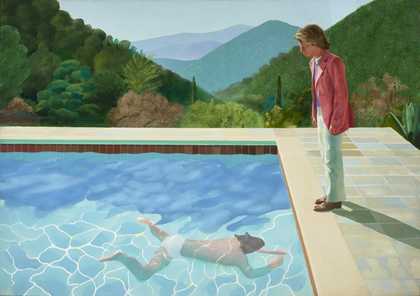

Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) 1972

Painted at the time of their break-up, Hockney’s then boyfriend, artist Peter Schlesinger, looks down at the figure of John St Clair, one of Hockney’s assistants, swimming underwater.

My Parents 1977

The artist’s parents, Kenneth and Laura Hockney.

Looking at Pictures on a Screen 1977

Henry Geldzahler studying reproductions of historic paintings in Hockney’s studio.

Room sixCLOSE LOOKING

From the beginning Hockney’s ability at drawing has provided the bedrock for his art. The earliest work here, a self-portrait, was made when he was a teenager. For Hockney, drawing is primarily a way of looking more intently.

Many of the drawings in this room – in pen and ink and in coloured crayon – are from the late 1960s and 1970s. At this time, Hockney developed a way of working that enabled him to capture the essence of a scene with the most economical of means: a few lines express the character of a sitter; one or two items conjure the feeling of a place or a moment in time.

Because Hockney tends to make drawings when away from the studio, many reflect his travels and include friends and boyfriends in exotic places, the loneliness of hotel rooms or the pleasures of a lazy lunch.

In the 1990s, Hockney proposed that many artists since the Renaissance had used optics as aids to depiction. He made a series of drawings using a camera lucida, a device which transfers the observed object to enable the artist to draw it with optical accuracy.

Room sevenA BIGGER PHOTOGRAPHY

For Hockney, the single-point perspective of photography could not communicate the experience of looking and living in the world. He described conventional photography as akin to ‘looking at the world from the point of view of a paralyzed Cyclops – for a split second.’ In contrast, he sought to create a photography that could accommodate different viewpoints as well as time and movement.

Hockney’s solution to this ‘flaw in photography’ was bound up with his renewed interest in cubism and the work of Picasso (he made many visits to the 1980 retrospective of Picasso at the Museum of Modern Art, New York). At first he used Polaroid film to create gridded multifaceted images that encourage the eye to experience each subject as it builds from its fragments of different viewpoints. In a matter of months he made 140 Polaroid works, but was ultimately dissatisfied with the effect of the borders on each Polaroid, so turned to 35mm film. Collages assembled from these borderless photographs allowed him to better approximate the complicated, multiple viewpoints for which he had been striving.

Through photography, Hockney revisited motifs and subjects used for his painting, from portraits and encounters to landscape and still life.

David Hockney

Going Up Garrowby Hill 2000

Private Collection © David Hockney

Room eightEXPERIENCES OF SPACE

Through the 1980s and 1990s Hockney’s paintings focused on the experience of looking. The freedom and variety of markmaking within his paintings of this period – descriptive and decorative, denoting space, material and experience – reflect the layers of memory and invention within them.

The post-cubist space that he created during this period was applied to landscapes and interior scenes of his new home in the Hollywood Hills. Landscape became the subject for paintings that were about moving through the terrain, the winding roads of Nichols Canyon and Outpost Drive being routes from his hilltop home to his studio. In these works flatness collides with illusion of spatial depth. But above all, these are paintings through which the eye dances, drawn by a sensuousness of line and colour where edges of viewpoints fold into and across each other.

Hockney’s painting describes the complexities of space and there was an interchange at this period between his designs for operas and his painting. One tool he exploited was reverse perspective, which in his stage designs was intended to make the audience feel directly involved in the production by exploiting fluctuations of deep and shallow space.

Room nineEXPERIENCES OF PLACE

In the late 1990s Hockney produced paintings of the landscapes of East Yorkshire and the Grand Canyon, and of his house and garden in the Hollywood Hills.

He was spending more time in Yorkshire and produced several works based on the drive from his mother’s seaside home to York, where he would visit his dying friend Jonathan Silver. He used multiple viewpoints to create a sense of his movement through the landscape, in particular up and down Garrowby Hill which rises from the Plain of York to the higher Wolds.

Hockney also determined to paint the vast spaces of the American landscape. When he saw the Grand Canyon described as ‘the despair of the painter’ he could not resist the challenge, capturing the view with multiple perspectives.

In depicting such places Hockney created an illusion of depth by the use of a foreground plain on which were arrayed objects, whether bails of wheat or small desert bushes. These derived directly from the abstract forms in his ‘very new paintings’ of a few years earlier (in the previous room) which themselves had been influenced by his stage work.

Room tenTHE WOLDS

In 2006 Hockney returned to his native Yorkshire to paint the changing light, space and landscape of the Wolds. Works such as The Road to Thwing 2006 and A Closer Winter Tunnel, February – March 2006 show that Hockney was painting outside on larger canvases, sometimes moving between several before assembling them to create the effect of a single image.

His move to a warehouse studio in Bridlington enabled him to create ever more complex and expansive pictures and begin exploring computer-generated images to aid their production.

Hockney shares with earlier artists including the Romantics an engagement with the landscape based on memory and observation, but his focus is different. ‘Artists thought the optical projection of nature was verisimilitude, which is what they were aiming for,’ he said, ‘But in the 21st century, I know that is not verisimilitude. Once you know that, when you go out to paint, you’ve got something else to do. I do not think the world looks like photographs. I think it looks a lot more glorious than that'

Room elevenTHE FOUR SEASONS

In 2010 Hockney began making multi-screen video works by fixing a number of cameras (one or each screen in the final work) to the outside of a vehicle which was then driven along the road at Woldgate, near Bridlington, Yorkshire. The result was like a cubist film, showing different aspects of the same scene as perceived by a moving observer.

These videos were originally shown in sequence but later Hockney reconfigured them as an immersive environment. As well as an exploration of the way a subject is seen over time, this work was a celebration of the miracle of the seasons. The experience of spring in 2002, after more than twenty years in seasonless California, had been one of the stimuli for Hockney settling in Yorkshire for about a decade.

Room twelveYORKSHIRE AND HOLLYWOOD

Hockney’s move from Yorkshire back to the Hollywood Hills in 2013 was marked by two different views of the landscape. His last work in Yorkshire was a sequence of 25 charcoal drawings celebrating the arrival of spring at five locations along the singletrack road running between Bridlington and Kilham that had provided him with much of the subject matter for his painting of the previous years. The first works he made on his return to California were two charcoal drawings of his poolside garden at morning and evening.

The last four years have seen an intense diversification of Hockney’s practice and the media he has used in his constant search for ways to represent the world of three and four dimensions, emotion and feeling, on a two-dimensional surface. Through arrangements in his studio of furniture and people – family, close friends and assistants – he finds new ways to represent the experience of looking. His art springs from a personal environment, yet, for Hockney, the most important place is the studio, where his consistent questioning and hard looking is manifested in pictures that encompass and transform how we see and respond to the world around us.

iPADS

Hockney has always welcomed the challenge of picturing transparency. The sheen of glass, passage of light, splash of water, all predominate within his paintings, drawings and photography since the mid-1960s. Something else that has characterised his work from the outset when, as a student, he started printmaking, is his constant desire to master new media. In 2009 glass and technology came together in his discovery of the iPhone, and the following year the iPad, as a new drawing instrument. On the iPhone he drew on the small back-lit glass screen with the side of his thumb, changing to a stylus with the larger screen of the iPad, to offer a different variety of line and a new luminosity of colour.

Using the iPad became habitual, almost replacing his sketchbook. Hockney continues to engage with his customary range of subjects – portraits and self-portraits, still lifes and landscapes – capturing the beauty of the everyday, most particularly through numerous varied views of his bedroom window in Bridlington. He collapses time and space by emailing images to friends and family, removing distance between the picture, its means of creation and its distribution.