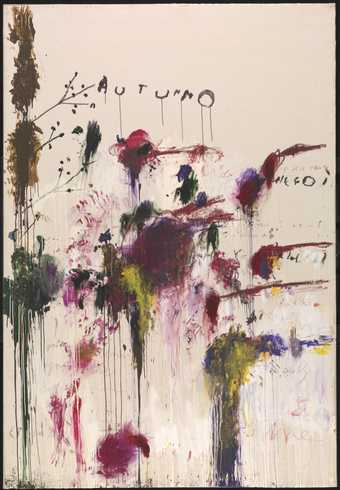

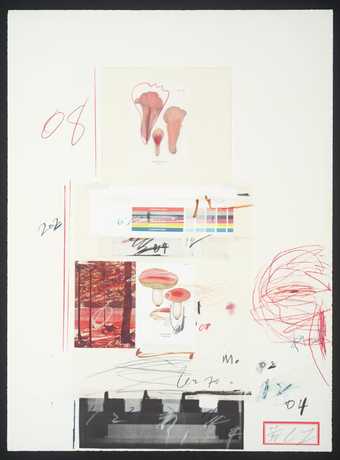

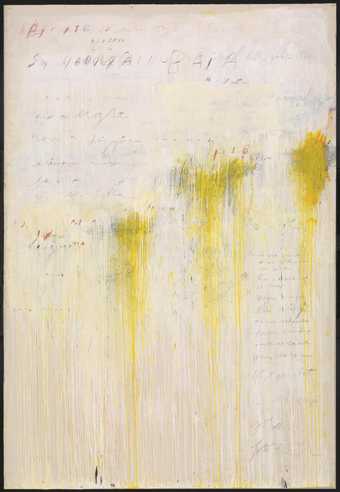

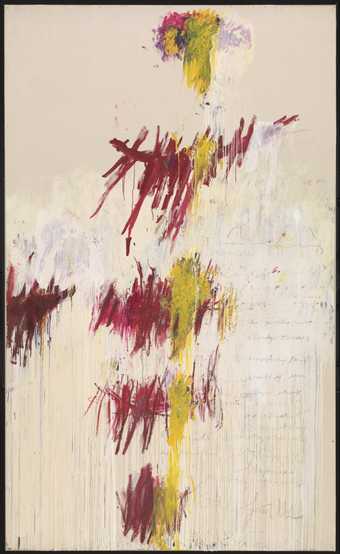

I’m Nicholas Serota, I’m Director of Tate and I’m curating this show with Nicholas Cullinan and we’re in the middle of hanging the show at the moment, we’re about halfway through the hang. And we’ve got most of the paintings in place, but the sculpture still has to find its own place within the show. I think here the story was one of an artist who works in a very intense way on a group of works at a given moment and then quite often has fallow periods between those groups, and so the show is organised in a way that reflects that with each room given over to a particular theme or cycle, and the challenge also is, you do all this in your mind when you are selecting the show, you plead desperately with people to lend these precious and fragile objects, and you just hope that when they all come into the room that they will speak to each other rather than crowd each other out. Twombly was really rather unusual I think from the early years, being equally active in both painting and sculpture, and in this first room you see an artist who you are very conscious of him working with his hands. He doesn’t make huge sculptures; the paintings are very much about the graphic mark, they are very much about his own reach and about the movement of the paint or the brush across the canvass; so you are very conscious all the way through this show, I think, of all this sense of a man making marks and trying to express himself both in painting and sculpture. As we leave that first room, we walk through a whole series of drawings that were almost automatic writing. You know, you close your eyes and you make a mark, and you make another mark and another mark, and you then build up an image which is coming from within, rather than a representation of something. And that became a principle that really underlay all the work from that point onwards. In this room that we have now moved in to, these are paintings that are much more liquid; they are painted across the whole canvas. Obviously the particular group that we are looking at here is a group which has many affinities, of course, with the work of Turner, and Twombly became very interested, I think, in Turner’s work in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, and he also became very interested in the idea of bringing into these paintings ideas that he had found expressed, not so much in painting but in poetry, and poets like Wilker and Keats and became ever more important for him. All the paintings in this room are very much concerned with water, and the sculptures in this room are equally very much related to the sea and to boats. Boats have always been a very important motif in Twombly’s work. As he moves on, you see this sense of him coming ever closer, I think, to the elements. Here we are in the final room of the show, where you see Twombly again reinventing his whole way of working. The paintings of course are entitled Bacchus Series and they relate obviously to the god of wine and to abandon and luxuriance and freedom and drunkenness, and a whole range of other things, but they were originally inspired by, or triggered really, rather than inspired, by Twombly’s interest in mannerist painting and the kind of, again the excesses of breaking the conventions of a kind of classical painting to try and do something totally new; and I think that they make a very interesting end to the show and take you back to that first room in which you saw him making these very graphic marks. Right the way through the show, you have this sense of a hand at work, whether it’s making sculpture or working across the canvas or making small drawings with quite elaborate and detailed elements in them, but you have this very strong sense of the physical presence of these paintings and sculptures, and you have the sense of an artist at work, and we want to give the sense of the intensity of being in the studio and being in the presence of the artist, and I hope that the show does that.