[Cornelia Parker]: Things seem to be going backwards... we're soaking ourselves in nostalgia.

It's almost like it's an innocence you know that's been lost.

[Exhibition visitor]: Hi Cornelia, what advice would you give to your younger self as a contemporary artist?

[Parker]: You don't need a studio. You don't need lots of money. You just need your imagination to be an artist. That's why it's really important to build up your battery as it were of things that stimulate you.

[Exhibition visitor]: There's a lot of humour that pervades your work, what do you find funny?

[Parker]: Yes I've been inspired by Tom and Jerry and Roadrunner and them being squashed or falling off cliffs or being blown up.

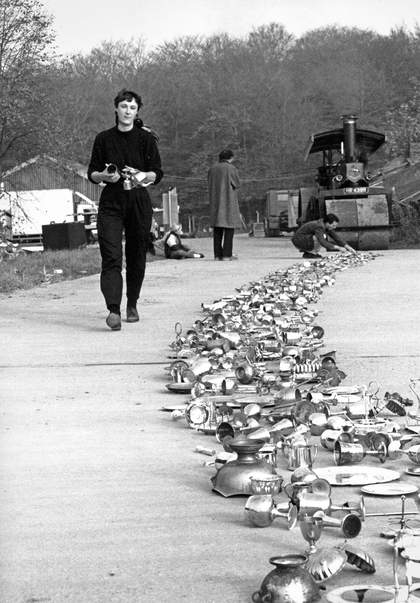

Thirty Pieces of Silver was run over by a steamroller and there's a film by Charlie Chaplin called Modern Times when he's working in a factory. He puts his boss's jacket on this hydraulic press and the press comes down and squashes the jacket. There's this giant fob watch it's like four times as big as it should be and that was when I thought "I want to crush things!"

[Exhibition visitor]: Hi Connie, I wondered how you persuaded the army, the police, Customs and Excise, the Houses of Parliament as well as a Nobel Prize-winning physicist to collaborate with you?

[Parker]: I enjoy collaborations because you're not in the studio you're out in the world reacting to people. Quite a lot of the people I've worked with are authority figures like the army, the police and they're the people who really sort of scare me a bit.

Another collaboration was with the Customs and Excise and they would tell you how creative it is that people try and smuggle drugs through, so they've got people wearing wigs with cocaine on their heads. There was a piece I did called Exhaled Cocaine. It's just a pile of burnt cocaine, that's what it is you know. I've got a big bag of the stuff and it's curiously still quite potent even though it's been burnt.

[Exhibition visitor]: My question is how do you ensure that a very complicated installation piece like the exploding shed has an ongoing integrity? How do you make sure that it is the same piece?

[Parker]: I think the wonderful thing about having the Tate own a piece like Cold Dark Matter is that it is their job to preserve the piece's integrity. I don't want to spend the rest of my life putting up old pieces when I'm trying to make new ones.

The exploded shed's not exactly the same every single time, it's slightly different. I like the pieces to be reflective of life itself. It's the opposite of sculpture say by Henry Moore which are solid lumps and never change.

I mean the explosion is aged 31 years old now, I mean it's very old and what I like about it it's now a time capsule.

Friends gave me stuff from their sheds, I went to car boot sales.

There's a Coke can drunk by one of the soldiers on the day it was exploded and also there's a piece of missile from the army demolition grounds.

Yeah there was a few little maverick things in there.

I remember my next-door neighbour they had a pram. I blew up the pram and then they wanted their pram back!

[Exhibition visitor]: Hi Cornelia is there another building that you would like to blow up?

[Parker]: I was hoping to blow up something bigger you know like a house but it just wasn't possible at the time. Perhaps I should do something really big if I'm gonna blow something up like I don't know... the Palace of Westminster perhaps? Perhaps I shouldn't say that...

[Exhibition visitor]: Hi Cornelia I'm really intrigued by the way you've lit War Room, could you tell us a bit more about the decisions around making it kind of create that undulating effect?

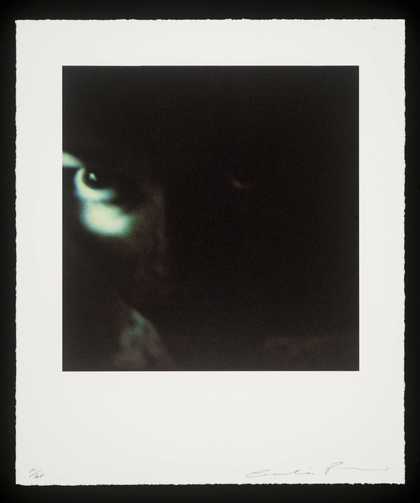

[Parker]: There's three light bulbs hanging down, it's a motif you know that I've used in other works like the Perpetual Canon or Island or Cold Dark Matter.

War Room has a companion piece War Machine which is a film. The material for it came from a poppy factory in Richmond. What I was struck by when I visited the factory was this the old machine that chopped the poppies out of this sheet of paper.

I quite liked the idea of making a giant tent out of it with a double moiré so it's two layers of the material.

It's disorientating, I mean some of the installers start to feel a bit motion sickness by the end of it.

I think there's three hundred thousand holes in the room and it reminds me of the war dead, you know the war graves, these regimented rows and you know war is a messy thing, it's not a neat thing.

[Exhibition visitor]: You use chalk in so many of your works made over the last 30 years why is it such an important material for you?

[Parker]: Chalk has been a fascinating material to work with over the years and I love it because it is literally the edge of England in a way. It's nature and culture and territory and all kinds of things embedded in this one material.

The most recent work which I just made for the Tate which is called Island. It's a greenhouse that's been painted on the inside with chalk from the White Cliffs of Dover. The strokes of chalk on the window panes are almost like marking time, so there's this idea of the greenhouse being the island and it's floating on a raft made of tiles from the Houses of Parliament.

I don't think the White Cliffs of Dover are going to protect us from climate change which is one of the things I'm thinking a lot about and I quite like the fact when the light inside the greenhouse shines it pulsates like a breath.

The white marks become black marks and we've got lots of black marks at the moment as an island.

Artist Cornelia Parker responds to questions from visitors to her 2022 exhibition at Tate Britain. What advice would she give to herself as a young artist? Why is she so drawn to chalk as an artistic medium? And which building would she like to blow up next?

Parker is one of Britain's best loved and most acclaimed contemporary artists. Always driven by curiosity, she reconfigures domestic objects to question our relationship with the world. Using transformation, playfulness and storytelling, she engages with important issues of our time, be it violence, ecology or human rights.