Cindy Sherman, my sparring partner, is perhaps one of the great practical jokes played on the art world, a world well known for its jokers. She is an eccentric artist in the guise of an ordinary person, who happens to be one of the most successful and influential artists of our time. Sherman came of age with the Big Bad Boy artists of the 1980s, and, unlike some of her blustery comrades, she is still big and bad – in fact, the biggest and baddest of them all. And she’s a girl! And a photographer: perhaps even the photographer responsible for photography’s rise as an art form in the last two decades.

Cindy and I first met years ago at a boxing gym, and when I asked our teacher, Carlos Ferrer, to describe her boxing style, he said without hesitation: ‘Fast and aggressive.’ In the ring, she reminds me of a pit bull terrier. When it comes to her work, she’s just as tenacious and ambitious. But she’s the judge and her standards are her own, based on a singular intuitive visual intelligence. For all the theories about angry feminism, or gender/identity ‘issues’, or female/sexual ‘victimisation’ or whatever (don’t quote me) about each and every series of Sherman’s work, she’s not playing that game. (Though she did let it slip that her 1999 series of misshapen dolls in various states of sexual depravity and distress was partly inspired by a sleazy, musclebound, well-connected prettyboy assistant who couldn’t deliver film to the lab properly.)

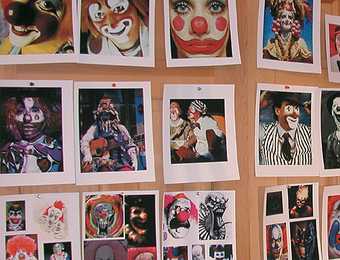

Sherman’s studio is as modest as she is: a large room that takes up roughly half her loft apartment in New York; a small shooting area with backdrops and desks strategically placed. Three months ago, this studio was so pristine you could lick the floor; today it’s a disaster area with clown clothing and props everywhere. Cindy’s making new work.

Betsy Berne

So this is a feminist studio, then?

Cindy Sherman

Oh yes [laughing]! See, I have breasts everywhere. I collect breasts!

Betsy Berne

How about the whole feminist thing?

Cindy Sherman

[Makes a face]

Betsy Berne

I always thought – even in my youth – that being a feminist was a given, that it was instinctive, so you didn’t have to discuss it. And if you had to discuss it, then something’s fishy. But maybe this is because we were at the tail-end of the generation that had to fight…

Cindy Sherman

Right, you feel that guilt – that’s how I feel about it too, but I don’t want to have to explain myself. The work is what it is and hopefully it’s seen as feminist work, or feminist-advised work, but I’m not going to go around espousing theoretical bullshit about feminist stuff.

Betsy Berne

When you were beginning, using yourself in the work, everybody made such a big feminist deal out of it. I had a photographer friend [the late Francesca Woodman] who also used herself in her pictures and she’d say, ‘I’m the one who’s always available and I know what I want.’ Did it begin that way for you?

Cindy Sherman

It was exactly like that. I did try using family members or friends, and once I paid an assistant. But even when I was paying somebody, I still wanted to rush through and get them out of the studio. I felt like I was imposing on them. Also, I got the feeling that they were having fun, to a certain extent, thinking this was like Halloween, or playing dress-up. The levels I try to get to are not about the having-fun part. I also realised that I myself don’t know exactly what I want from a picture, so it’s hard to articulate that to somebody else – anybody else. When I’m doing it myself, I’m really just using the mirror to summon something I don’t even know until I see it.

Betsy Berne

The instinctive part is the great thing about making art. The surprises you find are what’s interesting. Do you think you’re an intuitive artist?

Cindy Sherman

Oh, yeah, because sometimes in the past if I knew what the picture was going to be like I wouldn’t make it. It was almost like it was made already – the challenge is more about trying to make what you can’t think of.

Betsy Berne

How does an idea evolve for you – such as the clowns in your new work?

Cindy Sherman

First I try to figure out the costumes, and then probably a wig – and the make-up for clowns.

Betsy Berne

When did you think, ‘Oh, clowns!’?

Cindy Sherman

Well, that [points to a pair of silk pajamas with big fur-like buttons] is an old thing that I got at a yard sale ten years ago, pajamas turned into a clown outfit; it’s ugly and funky, but I liked it for that and it just helped everything come together. The reason I found it – you know how obsessive I was when I was trying to get started working – is that I was just cleaning every drawer and every closet in the studio trying to find some kind of inspiration.

Betsy Berne

Is that what you tend to do to get started? Clean and organise?

Cindy Sherman

Yeah. Also, I know that once I’m working I don’t want to be distracted by paperwork or emails, letters. So I try to get all those things out of the way too and the house cleaned so I can sort of…

Betsy Berne

Blast off?

Cindy Sherman

Yeah, right. So I took out the pajamas and a couple of other eccentric things that I’d been saving, although I didn’t have any particular thing I could apply them to. Then, when I started looking up clown pictures on line, I realised I could almost use anything, any item of clothing, T-shirts, jeans, and it could be a clown. And I had a couple of multicoloured wigs that I’d never used for a picture. So many things suddenly made sense for the clowns, for the whole idea. I’d been going through a struggle, particularly after 9/11; I couldn’t figure out what I wanted to say. I still wanted the work to be the same kind of mixture – intense, with a nasty side or an ugly side, but also with a real pathos about the characters – and [clowns] have an underlying sense of sadness while they’re trying to cheer people up. Clowns are sad, but they’re also psychotically, hysterically happy.

Betsy Berne

The funniest people are always the most miserable inside.

Cindy Sherman

Yeah, I like that balance – that you could be painted to look like you’re happy and still look like you’re sad underneath, or the opposite too. The more research I did the more levels I saw. There are a lot of creepy, sad, different emotions that I really like.

Betsy Berne

Did you like clowns as a kid?

Cindy Sherman

No, I never went to see them. I was about 30 when I first went to the circus.

Betsy Berne

I never went to the circus either. My mother said it was commercial bullshit, so I thought that’s that. Another thing – how important is music when you work?

Cindy Sherman

Really important. I can’t work without it. And it has to be the right kind, because if it’s not then I get into a bad mood. I work with a remote so that I can change CDs instantly if I need to. When I’m working I usually buy about 30 new CDs every couple of weeks.

Betsy Berne

Can shopping give you ideas?

Cindy Sherman

[Laughs] I think it can – sometimes what I like, fashion-wise, is so theatrical I’ll buy it even if I can’t wear it. I do get inspired by how things are made, by fashion as art form.

Betsy Berne

Some designers think it’s pretentious to equate fashion with art, but at least fashion is what it is. Appreciating it is part of being a visual person.

Cindy Sherman

Right, right.

Betsy Berne

Now that I don’t paint, creating an outfit can be my major visual highlight for the day. Or at least that’s my excuse for buying too many clothes.

Cindy Sherman

Except it’s the same thing for me – and I’m still doing visual work [laughs].

Betsy Berne

How do you deal with the long periods when you aren’t making work?

Cindy Sherman

When I do work, I get so much done in such a concentrated time that once I’m through a series, I’m so drained I don’t want to get near the camera.

Betsy Berne

It sounds like writing. Do you think you’re telling stories without knowing it?

Cindy Sherman

I try to get something going with the characters so that they give more information than what you see in terms of wigs and clothes. I’d like people to fantasise about this person’s life or what they’re thinking or what’s inside their head, so I guess that’s like telling a story.

Betsy Berne

Which is worse: when you’re working or when you’re not working?

Cindy Sherman

What’s worse is when I’m not working when I want to be working. The worst part of it for me is when I go to functions and feel like I have nothing to say because I can’t say what I’m working on. When there’s no focus with the work I feel I can’t communicate with people.

Betsy Berne

Work is a great excuse to be alone. Would you say that you’re a loner?

Cindy Sherman

Oh, yeah, Paul [her boyfriend, director Paul H-O] and I both are.

Betsy Berne

Do you think your work has more humour than it gets credit for?

Cindy Sherman

I think it’s more funny than scary.

Betsy Berne

How do you get past all the crap critics often write about you?

Cindy ShermanSometimes I’ve read stuff that never occurred to me. Elizabeth Hess once said something about ‘deconstruction’ [laughs]. It was when I used [fake] body parts in the work instead of myself; maybe I appear in the reflection of some things. Hess said that ‘I’ was gradually moving out of the work and so she analysed the ‘deconstruction’ of it. I’d never thought of that [laughs]! That’s the only time a light bulb went off. Because to me I was just trying to see if I could make pictures that I wasn’t in.

Betsy Berne

Do you resent people reading your personal life into your work?

Cindy Sherman

I just think it’s funny.

Betsy Berne

What about everybody saying you’re so nice? Is it just easier that way?

Cindy Sherman

[Laughs] Yeah, well, some people I really like. Then mostly with other people I’m polite because my mother told me to be polite, to ‘be a good girl’.

Betsy Berne

It’s simplistic, but if you’re raised to be a ‘good girl’, your work is the only private place where you can do whatever the hell you want and rebel.

Cindy Sherman

Right, that’s true, because it’s an outlet for anger and lots of other things.

Betsy Berne

In one of the early articles about you, you said, ‘I’m doing one of the stupidest things in the world and they’re actually falling for it.’ Do you still feel that way?

Cindy Sherman

Well, I was feeling guilty in the beginning; it was frustrating to be successful when a lot of my friends weren’t. Also, I was constantly being reminded of that by people in my family making jokes like, ‘Oh, yes, she’s still just dressing up like she did when she was a kid,’ or ‘It doesn’t take any brains to be doing what she’s doing.’ So I guess I was thinking, maybe I am still just dressing up, because I don’t theorise when I work. I would read theoretical stuff about my work and think, ‘What? Where did they get that?’ The work was so intuitive for me, I didn’t know where it was coming from. So I thought I had better not say anything or I’d blow it.

Betsy Berne

Do you think viewers like a challenge or prefer to be told what to think?

Cindy Sherman

You know what? I don’t really care.

About the artist

Cindy Sherman was born in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, in 1954. She studied painting at State University College, Buffalo, New York, where she failed her introductory course in photography. After graduating in 1976, she produced the 69 black-and-white photographs that comprise her series Untitled Film Stills 1977–80). The images, which resemble movie stills, all portray Sherman herself in a multitude of guises: B-movie characters, film noir victims or European New Wave cinema stars. Since the early 1980s, Sherman has photographed herself in a multitude of masquerades that continue to explore both cinematic traditions – particularly horror – and conventions of representation in popular culture. The construction of womanas- image is dominant in her photographs. Her works in colour, such as Centerfolds (1981) and Fashion 1983–4, explore themes of voyeurism and fantasy. In 1996, Cindy Sherman made her directorial dbut with The Office Killer, a film starring Carol Kane. Her work has been shown internationally in more than 150 group exhibitions and 75 solo shows, most notably in 1997 when The Complete Untitled Film Stills was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.