One of the beauties of my life is that I never work. I’m lazy and I have no other way to work. I teach this to my students: you must wait and hope – there’s nothing else you can do. And when you have an idea, you can do it in ten minutes.

Nobody comes here – I don’t like it when people come here. There is nothing to see – most of the time I give interviews at a café in Paris, and it’s good. I’m so far from Paris, here in Malakoff, people don’t know where it is. I consider this room to be my studio, but really there’s nothing here. It’s like a place where you live. The only useful thing about the studio is that after some time you can imagine something, a forest, for example: I walk in it and today it is nothing for me, but perhaps in two weeks it will become something.

I began to work as an artist when I began to be an adult, when I understood that my childhood was finished, and was dead. I think we all have somebody who is dead inside of us. A dead child. I remember the Little Christian that is dead inside me.

I stopped going to school at about age 12, and I was very crazy, and I stayed at home. One day I made a little object in plasticine and my parents said it was good. So I started to make more, and to make drawings, and I began to make large paintings in my bedroom. I have a sweet brother who said to me then, ‘You must learn something and you are going to speak English doing your work.’

So all the time I painted, he spoke to me in English, and that’s the reason I can speak a little English. I was actually painting a large portrait, with plenty of people and stories, so there was plenty to talk about. My brother is now a professor of linguistics.

I come to my studio every day at 10.30, and I stay and do nothing. I go to Paris sometimes. I have a few ideas. To be very pretentious, sometimes I believe it is mystical. Sometimes you find nothing, and then you find some-thing you love to do. Sometimes you make mistakes, but some-times it’s true. In two minutes, you understand what you must do for the next two years. Sometimes it’s in the studio, but other times it’s walking in the street or reading a magazine. It’s a good life, being an artist, because you do what you want.

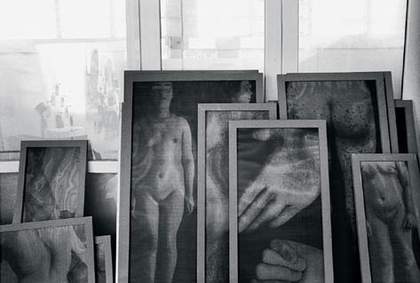

Something like 60 per cent of my work is destroyed after every show. And if it’s not destroyed, it’s removed, or I’ll mix one piece with another. When I make a show it’s like when you arrive at home and you open your fridge at night and there’s two potatoes and one sausage and two eggs, and with all that you make something to eat. I try to make something with what is in my ‘fridge’.

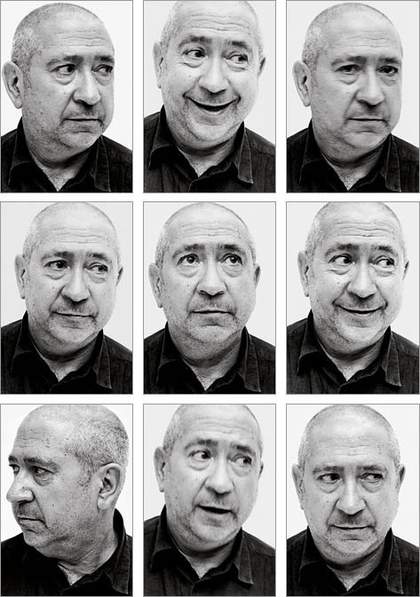

What drives me as an artist is that I think everyone is unique, yet everyone disappears so quickly. I made a large work called The Reserve of Dead Swiss (1990) and all the people in photographs in the work are dead. We hate to see the dead, yet we love them, we appreciate them. Human. That’s all we can say. Everyone is unique and important. But I like something Napoleon said when he saw many of his dead soldiers on a battlefield: ‘Oh, no problem – one night of love in Paris and you can replace everybody.’

I’m always a beginner, and the most important thing is always the next piece. We artists never know if we can do it again. You have done something – and most of the time I hate what I have done a few years ago – and you don’t know if you can do something now. The good artists are usually the very young or the very old. The ones who are very young are so stupid that they have no fear. And when they are very old they aren’t afraid any more. In the meantime, you are always, always, afraid.

Being an artist does not make me happy. You have no reason to wake up in the morning. That’s my big problem. Why don’t I look at the TV all day? I’ve made no reason to come here. But if I stop totally, then nothing happens. I always hoped to open a bakery in Bratislava – with a very fat wife and ten children! – but I shall never do that. This is a lonely life. Some of my friends love to make gardens or have cars, and I understand that. But for me I want to do nothing, to have no distraction. I love to eat, I love to drink, I like to see friends. I’m not always alone. I am not a good cook, but I love to cook. I occasionally have this dream that I am a teacher, but I am a bad teacher and I don’t go to my school very often! And what is very lonely is that nobody else can say anything useful to you about your work. Even Annette [Messager] never comes here. She never looks at my work. There is a beautiful story in Proust: A sad man whose wife has just died sees a friend going to commit suicide. They pass through a garden and he says to his friend, ‘Look at these flowers, so beautiful. Look at the blue sky.’ Seeing these things, the friend forgets to kill himself. He survives because he forgets. Sometimes we need to forget. For this reason, I do nothing, and I only wait to die. We must be friendly with dying. To be alive is to be honest.

Christian Boltanski, blue tent in studio

Photography: Michael Sanders

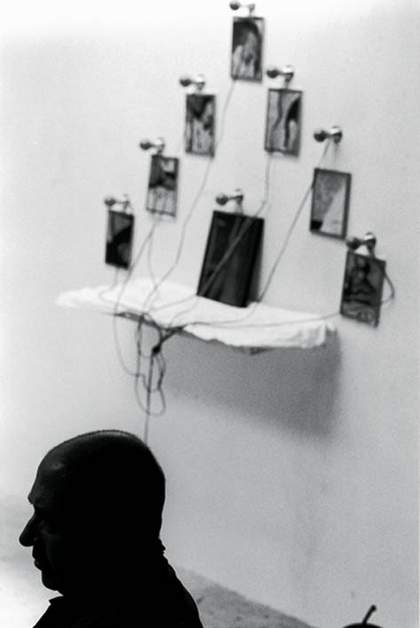

This blue tent here is something I am working on for a show in Mexico. The shapes are going to be different, there will be ten of them, and there will be dark shadows, and this blue material. This thing I’ve built is one way for me to try something out in the studio, but for the actual installation I’m going to send a letter. That’s all.

It’s a 600-metre-square space, and I’m going to send nothing. I’m sure they can find enough pieces of wood, and I’ll need balls. I shall stay for one week or ten days and I’ll make it there. And then I will have the thing destroyed. That’s something I like also. They give me money and I give them nothing.

When I make a large show, I often try to have a beginning and an end, because emotion comes from time. But it’s a different kind of time than theatre or cinema. I mean, when you read a book, you have, say, a young girl who is happy on one page, and you turn the page and now she is dying. That quality of emotion comes when you have some kind of a shock. When I make a picture, I try to create different kinds of space, and even different kinds of shock, to have a beginning and to have a sweep of emotion. My work is a little like theatre, but it’s also always so different. I’m like a musician, I can play my work and I can play my work better, or worse, depending on the place where I am showing. It’s theatre without text, without spectacle. What I wish to do is something between theatre and installation.

I’ve never stopped painting. I’m a painter. Absolutely. I’m a very traditional artist. Making paintings and doing nothing. The big difference between painter and artist is that some art is to do with space and other art is to do with time. Music, literature or theatre, these things do something with time. Painting does something with space. When we see a movie, there is a beginning and an end, most of the time. When you see a painting, you can look at it for ten minutes or six hours, and you can move around. The big ‘cut’, in terms of media, I think, is time or space. There are some artist videos, like Bruce Nauman’s, which are more like painting, really, because they are a space product, like sculpture. But there are also artist videos that are more like cinema, because they have a beginning, an end, and we sit down to watch them.

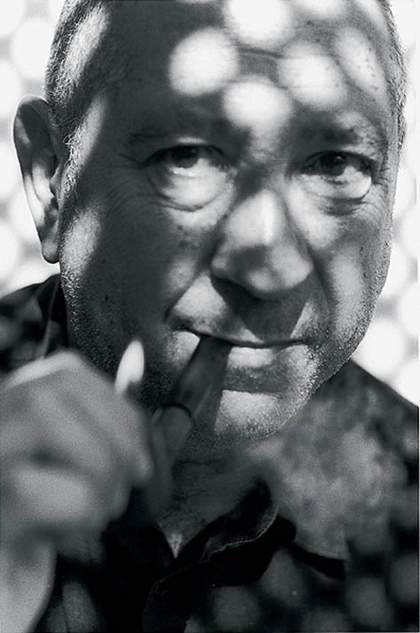

About the artist

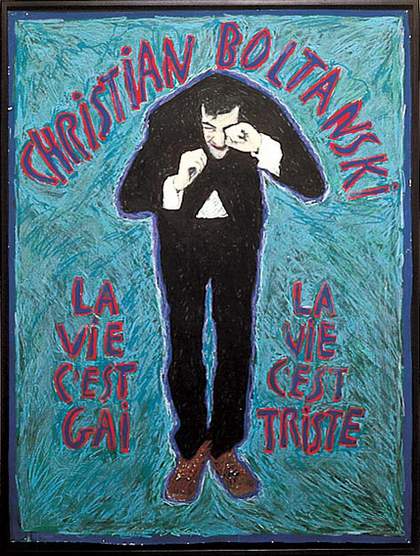

Christian Boltanski was born in Paris in 1944. His artistic career began when he left formal education at the age of 12, at which point he started painting and drawing. Since the 1960s, he has worked with the ephemera of the human experience, from obituary photographs to rusted biscuit tins. Several of Boltanski’s projects have used actual lost property from public spaces, such as railway stations, creating collections which memorialise the unknown owners in the cacophony of personal effects.

Boltanski has exhibited internationally at museums including: Musée d’art modern de la ville de Paris; Kunsthalle Wien; Stedelijk van Abbemuseum. Eindhoven; Whitechapel Art Gallery, London; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angelis; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki; Malmö Konsthall; National Museum of Contemporary Art, Oslo; Museum Ludwig Köln; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Regina Sofia, Madrid.

His work has been featured in Documenta (1972, 1986) at the Venice Biennale (1993, 1996), and at the Carnegie International at the Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh (1991). Boltanski lives in Malakoff, a suburb of Paris, with equally renowned artist Annette Messager.